“They named a brandy after Napoleon, they made a herring out ofBismarck and the Führer is going to end up as a piece of cheese!” — Colonel Ehrhardt

“They named a brandy after Napoleon, they made a herring out ofBismarck and the Führer is going to end up as a piece of cheese!” — Colonel Ehrhardt

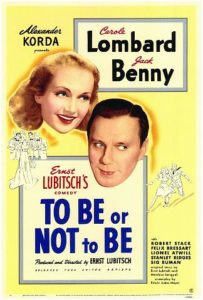

Jack Benny, who had been a successful vaudevillian and was, in the 1940s, a great success on radio, had less success in the movies, though some of his films—The Horn Blows at Midnight and George Washington Slept Here, often the targets of many of his jokes—were not nearly as bad as he pretended. He would reach his zenith, however, on television, with the fifteen-year-long run of The Jack Benny Program and countless guest TV appearances with the major stars of the day. His To Be or Not to Be in 1942 is his only real movie success.

Carole Lombard, who is Benny’s co-star, was the classic blond bombshell, more so, I think, than the actress to whom that title has been long ascribed, more sophisticated, without the racy overlay of Jean Harlow. The originator of expressions like “dumb blonde” and “she’s so blonde,” Lombard was, at the time, the unquestioned mistress of the screwball comedy and, off screen, could curse with the best of her male colleagues. Also a luscious romantic player, her leading men included first husband William Powell in My Man Godfrey, Fredric March in Nothing Sacred and James Stewart in Made for Each Other.

Married to Clark Gable at the time of filming To Be or Not to Be, Lombard was killed in a plane crash on her return from a bond drive. She had cancelled her train journey in favor of the “faster” plane, so anxious was she to attend to rumors of her husband’s affair back in Hollywood. The film had been finished and scheduled for release, but its premiere was postponed for two months. Jack Benny was so grieved that his first radio program following her death was cancelled.

The director, Ernst Lubitsch, was not, as some assume, among the many German émigrés who fled Hitler’s Third Reich: he had arrived in Hollywood in 1922—old Adolf would spend most of 1924 in Landsberg Prison—and began his fame in the silents, with such delights as The Marriage Circle and So This Is Paris. Before and after 1942, he was well established as the master of the sophisticated comedy and what came to be known as “the Lubitsch Touch,” epitomized in such films as Ninotchka, The Shop Around the Corner, That Uncertain Feeling and Heaven Can Wait, which Warren Beatty had a fair go at remaking thirty-five years later.

With To Be or Not to Be, Lubitsch forgoes his usual satire of the idle rich and shallow socialites and concentrates instead on mocking the Nazis, which he could feel confident in so doing without fear of reprisal, as Hitler had reached his momentary zenith and soon, if not already, there would be his failed Russian and North African campaigns and the beginning of the Third Reich’s plummet downward into flames and annihilation.

With To Be or Not to Be, Lubitsch forgoes his usual satire of the idle rich and shallow socialites and concentrates instead on mocking the Nazis, which he could feel confident in so doing without fear of reprisal, as Hitler had reached his momentary zenith and soon, if not already, there would be his failed Russian and North African campaigns and the beginning of the Third Reich’s plummet downward into flames and annihilation.

Any summary of the complicated plot of To Be or Not to Be, while here still seemingly extended, can only touch upon the high points:

In the opening, a narrator intones, in stiff newsreel style, that here is Warsaw, August 1939. A crowd of people in the streets stop in their tracks and gawk at a seemingly impossible apparition, a figure, “a little man with a mustache,” walking the streets. Could it be . . . ? Why would he be in Warsaw? Adolf Hitler!? As the figure approaches a delicatessen, the narrator continues: “ . . . he’s a vegetarian, yet he sometimes doesn’t always stick to his diet. Sometimes he swallows up whole countries. Does he want to eat up Poland, too?”

Turns out, this is a scene staged by a Polish theater company. Hitler is an actor, Bronski (Tom Dugan), trying to prove that, appropriately attired and made up, he can fool the populace. Backstage now, the members of the company argue among themselves and the producer, Dobosh (Charles Halton, the bank examiner in It’s a Wonderful Life), says that he doesn’t want a funny line in a certain place.

Turns out, this is a scene staged by a Polish theater company. Hitler is an actor, Bronski (Tom Dugan), trying to prove that, appropriately attired and made up, he can fool the populace. Backstage now, the members of the company argue among themselves and the producer, Dobosh (Charles Halton, the bank examiner in It’s a Wonderful Life), says that he doesn’t want a funny line in a certain place.

During this rehearsal, Greenberg (Felix Bressart) says to Rawitch (Lionel Atwill, the police inspector with the mechanical arm in Son of Frankenstein), “Mr. Rawitch, what you are I wouldn’t eat.” Rawitch replies, “How dare you call me a ham!”

With a return to the street scene, Bronski still insists he can pass as the Führer until a little girl walks up to him and says, “May I have your autograph, Mr. Bronski?”

Before that night’s performance of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, two spear-carrying actors complain about their unvaried parts. One, Bronski, says they’re always carrying spears—in Act I, Act II and Act III. The other, Greenberg, reveals that he has always dreamed of playing Shylock in The Merchant of Venice with those lines about being a Jew: “If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us do we not die?”

Before that night’s performance of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, two spear-carrying actors complain about their unvaried parts. One, Bronski, says they’re always carrying spears—in Act I, Act II and Act III. The other, Greenberg, reveals that he has always dreamed of playing Shylock in The Merchant of Venice with those lines about being a Jew: “If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us do we not die?”

For Hamlet’s famous soliloquy, the “great, great” actor Joseph Tura (Benny) approaches the footlights. After receiving help from the prompter on the very first line—“To be or not to be . . . ”—he notices a member of the audience, a good-looking military officer, moving through a row of seats to leave.

Back stage, Tura’s wife, Maria (Lombard), receives in her dressing room the officer who had left his seat, Stanislav Sobinski (Robert Stack), a lieutenant in the Polish division of the Royal Air Force. He’s much enamored of her and, having read all her interviews, wants to know about her pet gold fish and her farm, though she feigns remembrance, then changes the subject. And she is much impressed by a man “who could drop,” he brags, “three tons of dynamite in two minutes.”

Back stage, Tura’s wife, Maria (Lombard), receives in her dressing room the officer who had left his seat, Stanislav Sobinski (Robert Stack), a lieutenant in the Polish division of the Royal Air Force. He’s much enamored of her and, having read all her interviews, wants to know about her pet gold fish and her farm, though she feigns remembrance, then changes the subject. And she is much impressed by a man “who could drop,” he brags, “three tons of dynamite in two minutes.”

After his performance that evening, Joseph Tura says to his wife, “Someone walked out on me. Tell me, Maria—am I losing my grip?”

“Oh, of course not, darling. I’m so sorry.”

“But he walked out on me.”

“Maybe he didn’t feel well. Maybe he had to leave. Maybe he had a sudden heart attack.”

“I hope so.”

“If he stayed he might have died.”

“Maybe he’s dead already,” Tura reassures himself. “Oh, darling, you are so comforting.”

Maria and the lieutenant began seeing one another behind Tura’s back, but Sobinski is soon called away when Germany invades and conquers Poland.

Apparently a friend of a group of pilots, a Polish Resistance leader, Professor Siletsky (Stanley Ridges), says he’s going to Warsaw and will be glad to take any messages to their relatives. Sobinski asks Siletsky to deliver a message, “To be or not to be,” to Maria Tura, that she’ll know what it means.

But Sobinski thinks it strange that Siletsky doesn’t know the famous Polish actress Maria Tura, and realizes, if he should be a Nazi agent, the people in the messages would be prey for the Nazis. Sobinski reports his suspicions to the Underground leaders (Halliwell Hobbes and Miles Mander), who dispatch him toWarsaw to warn the Resistance. Siletsky has already arrived, but Sobinski gives the message to Maria to pass to the Underground.

But Sobinski thinks it strange that Siletsky doesn’t know the famous Polish actress Maria Tura, and realizes, if he should be a Nazi agent, the people in the messages would be prey for the Nazis. Sobinski reports his suspicions to the Underground leaders (Halliwell Hobbes and Miles Mander), who dispatch him toWarsaw to warn the Resistance. Siletsky has already arrived, but Sobinski gives the message to Maria to pass to the Underground.

Siletsky has Maria brought to him to discover the meaning of “To be or not to be.” She plays up to him. A Nazi officer—actually one of Tura’s actors—enters, announcing that Siletsky is urgently needed at Gestapo headquarters.

The exterior of Tura’s theater and its inside, complete with props and costumed Nazis, have been recreated as the headquarters for Siletsky’s benefit, and Tura has become Colonel Ehrhardt, the Gestapo commander in Warsaw. Siletsky passes on the names Sobinski had given him and reveals that “To be or not to be” is merely the code for a rendezvous, which arouses Tura’s suspicions about his wife.

Professor Siletsky remarks, “You know, you’re quite famous in London, colonel. They call you ‘Concentration Camp Ehrhardt.’ ” Ehrhardt laughs and says, “Yes, yes—we do the concentrating and the Poles do the camping.” Then, when Siletsky asks the disguised Tura questions he cannot answer, he stalls by repeating, “So-o-o-o, they call me ‘Concentrate Camp Ehrhardt.’ ” Siletsky becomes suspicious, draws a gun on Ehrhardt, but is killed in his attempt to escape.

Professor Siletsky remarks, “You know, you’re quite famous in London, colonel. They call you ‘Concentration Camp Ehrhardt.’ ” Ehrhardt laughs and says, “Yes, yes—we do the concentrating and the Poles do the camping.” Then, when Siletsky asks the disguised Tura questions he cannot answer, he stalls by repeating, “So-o-o-o, they call me ‘Concentrate Camp Ehrhardt.’ ” Siletsky becomes suspicious, draws a gun on Ehrhardt, but is killed in his attempt to escape.

Tura now goes to Siletsky’s hotel disguised at Siletsky with fake beard and glasses, to steal some critical papers and is taken to meet the real Ehrhardt (Sig Ruman, the Nazi barracks warden Schulz in Stalag 17). Tura learns that Hitler himself will arrive in Warsaw the following day.

Later, the body of the real Siletsky is found, and Ehrhardt arranges another meeting with “Siletsky” and sends him alone into a room with the body, anxiously waiting outside for a confession. Tura shaves the beard off the body, then attaches a fake beard which he conveniently has in his pocket—ours is not to reason, only to accept. After a long, patient exchange between the two, “Siletsky” calmly reiterating that, yes, it looks pretty bad for him, he tricks Ehrhardt into checking the beard on the body. He finds it comes off! Tura’s Siletsky is safe and taken by Ehrhardt to be the real professor.

In the meantime, unaware of Tura’s successful hoax, Maria has sent more of the theater troupe disguised as Nazis to rescue him, headed by Rawitch. Now they yank off Tura’s false beard, proving he is the imposter, and take him to a presumed Nazi prison. The dead man was the real Siletsky after all!

In the meantime, unaware of Tura’s successful hoax, Maria has sent more of the theater troupe disguised as Nazis to rescue him, headed by Rawitch. Now they yank off Tura’s false beard, proving he is the imposter, and take him to a presumed Nazi prison. The dead man was the real Siletsky after all!

Ehrhardt turns to his assistant Schultz (Henry Victor) and admonishes him for getting him into yet another compromising situation. Much later, when Ehrhardt is at wits’ end, his hand by chance falls on a revolver in its holster. Behind a closed door, a gun shot is heard, a “thud” and a shout, as so often from Ehrhardt: “Schultz!”

As a ruse to leave the country, members of Tura’s troupe appear dressed as Nazis when the real Nazis honor Hitler at the theater. After Hitler has arrived and the show has begun, Greenberg gets a chance to recite his Shylock monologue. While the guards are distracted, Bronski, again dressed as Hitler, leads Tura and his actors to Hitler’s car and they drive away. Now with Maria, whom they pick up from her apartment, they board Hitler’s plane, Sobinski flying toward Scotland.

Aboard the plane, Bronski, still in his Führer disguise, orders the two Nazi pilots to jump out of the plane. To show their programmed, unquestioning obedience—the infamous “I-was-only-obeying-orders” reflex—the two pilots do so.

Aboard the plane, Bronski, still in his Führer disguise, orders the two Nazi pilots to jump out of the plane. To show their programmed, unquestioning obedience—the infamous “I-was-only-obeying-orders” reflex—the two pilots do so.

Bronski, still in his disguise, parachutes onto a haystack in Scotland. A farmer (Alec Craig’s only appearance/line) remarks to his friend (James Finlayson, one of the great clowns of the silents), “First it was Hess, now a ham!” Whether intentional or not, it ties in with Rawitch’s earlier response to being called a ham actor.

On stage once again, Tura is into his Hamlet soliloquy and is careful to see that Sobinski is in the audience—and not leaving. But, suddenly, another young officer is now leaving his seat, working his way through the row.

And, implied, it all starts over again!

Which—the idea of seeing the film again—wouldn’t be all that bad, as it’s quick-paced, thoroughly engrossing and hilarious in the extreme. The lines, the repartee, the jokes, if more urbane and more often on target that the Mel Brooks’ splashy, uneven remake in 1983, are never-ending, though subtle and rapid-fire enough to easily slip by in an initial viewing. The plot, if over-complicated for a comedy, is nonetheless executed with guarded clarity, the kind of movie that requires seeing repeatedly. It brilliantly lampoons the Nazis, accenting their sickness and all the paraphernalia of their brand of grotesquerie. At every turn the emphasis is on “Heil, Hitler!,” “Heil, Hitler!,” “Heil, Hitler!,” all the more comic.

Which—the idea of seeing the film again—wouldn’t be all that bad, as it’s quick-paced, thoroughly engrossing and hilarious in the extreme. The lines, the repartee, the jokes, if more urbane and more often on target that the Mel Brooks’ splashy, uneven remake in 1983, are never-ending, though subtle and rapid-fire enough to easily slip by in an initial viewing. The plot, if over-complicated for a comedy, is nonetheless executed with guarded clarity, the kind of movie that requires seeing repeatedly. It brilliantly lampoons the Nazis, accenting their sickness and all the paraphernalia of their brand of grotesquerie. At every turn the emphasis is on “Heil, Hitler!,” “Heil, Hitler!,” “Heil, Hitler!,” all the more comic.

The redoubtable Jack Benny is front and center, with more screen time than any one else, and rightly so, as he is in complete command of the proceedings. Absent are most of the Benny trademarks—the long pauses, the folded arms, the bemused look (one would be tempted to say “wonderfully so,” but that would be unfair)—although some traits, like the voice inflection and the vacant stare (distinct from the bemused one) are present. In the guises of Ehrhardt and Siletsky, Benny seems to expand his range and capture something of the inexplicable, that rare gift of the actor stepping outside of himself; as Hamlet reciting his soliloquy, he is fully his character—awkward and undramatic, any insight into his role totally eluding him.

If Jack Benny dominates in To Be, then that means that Carole Lombard is absent from the screen more than one would like, especially in the latter half, unfortunate, considering this is the last film for the dazzling and vivacious actress. Upon her entrance, lusciously attired in a floor-length satin gown, she says, “Think of me being flogged in the darkness. I scream. Suddenly the lights go on and the audience discovers me on the floor in this gorgeous dress!”

If Jack Benny dominates in To Be, then that means that Carole Lombard is absent from the screen more than one would like, especially in the latter half, unfortunate, considering this is the last film for the dazzling and vivacious actress. Upon her entrance, lusciously attired in a floor-length satin gown, she says, “Think of me being flogged in the darkness. I scream. Suddenly the lights go on and the audience discovers me on the floor in this gorgeous dress!”

While wishing for more appearances here, why not wish for another film from her—and another? Why not wish that she had taken that slow train to Hollywoodinstead of the plane? None of this is possible, for life is what it is; fate, that handmaiden (henchman?) of time itself, moves on, irrevocably.

As with the actors, To Be comes with a stellar production cast. Cinematographer Rudolf Maté would receive in his career five Oscar nominations—no wins, unfortunately—for Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent, That Hamilton Woman (also 1942), The Pride of the Yankees, Sahara and Cover Girl. Dorothy Spencer, a legendary film editor, was also responsible for Stagecoach,Decision Before Dawn, Cleopatra (1964) and Earthquake—all unsuccessful Oscar nominations as well.

1942 was the year of Mrs. Miniver, Kings Row and Yankee Doodle Dandy, and Lubitsch was overlooked at Oscar time, but would be nominated for The Love Parade, The Patriot and Heaven Can Wait.

Composer Werner R. Heymann, who did have to flee Germany because of Hitler and who scored other Lubitsch pictures, including Ninotchka and The Shop Around the Corner, was unaccountably nominated for Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture. The winner in that categroy was, perhaps to no surprise, Max Steiner for Now, Voyager. Heymann did far superior work in other films. The main title is an orchestration by Alexander Glazunov of Chopin’s Polonaise in A, Op. 40, No. 1, subtitled “Military,” appropriate to the film. Much of the rest of the score consists of rather nondescript music and much stock material by Miklós Rózsa.

Composer Werner R. Heymann, who did have to flee Germany because of Hitler and who scored other Lubitsch pictures, including Ninotchka and The Shop Around the Corner, was unaccountably nominated for Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture. The winner in that categroy was, perhaps to no surprise, Max Steiner for Now, Voyager. Heymann did far superior work in other films. The main title is an orchestration by Alexander Glazunov of Chopin’s Polonaise in A, Op. 40, No. 1, subtitled “Military,” appropriate to the film. Much of the rest of the score consists of rather nondescript music and much stock material by Miklós Rózsa.

Strange in retrospect, especially now considering the graphic, often tasteless images on recent movie screens and the brutality about in the world, To Be Or Not to Be was, at the time of its release, considered offensive and unfunny in satirizing the Nazi occupation of Warsaw and the Nazis in general. With World War II at its height and Americans seeing little humor in the proceedings, that’s understandable. The humor, in fact, holds up surprisingly well, even funnier today, somehow even more timely, and without resorting to slapstick.