“But you have retired, Holmes. We heard you are living the life of a hermit among your bees and your books in a small farm upon the South Downs.”

—— Dr. Watson to Sherlock Holmes in His Last Bow (1917)

Dr. John Watson, companion and off-and-on sharer of the flat at 221B Baker Street, brother Mycroft and landlady Mrs. Hudson have died, and that famous personality who knew them all has moved to Sussex, in southeastern England. Sherlock Holmes, now ninety-three and with failing memory, has retired from his career as consulting detective and turned to an earlier passion—beekeeping.

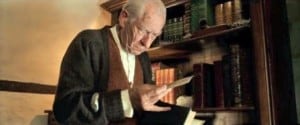

In an aspect unimagined before, and never covered, nor even thought of, by Holmes’ creator, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, in Mr. Holmes Sherlock has become old, in retirement and “in,” as well it seems, his dotage. He appears less tall than before, no longer, as Dr. Watson described him, “rather over six feet”; the “thin, hawk-like nose” has lost its well-defined edge and those “sharp and piercing” eyes have dulled somewhat—all due to the accumulated years and perhaps to illness.

Coming into his own against younger and more physical personifications of the great detective currently on the scene—Benedict Cumberbatch in an ongoing BBC/PBS series and Robert Downey, Jr. in two theatrical movies and a third one to come—the seventy-six-year-old Ian McKellen brings a totally new approach to the famous character. Clearly, McKellen is presenting a new version of, a new insight into, Holmes, not one necessitated by disguise or make-up, a key element in the younger man’s solution of crimes, but by adapting to the unavoidable state of this actor’s “mature years.” He is, however, made to look his best in the many flashbacks to Holmes’ earlier days, though make-up is still required to convey the detective at ninety-three.

Coming into his own against younger and more physical personifications of the great detective currently on the scene—Benedict Cumberbatch in an ongoing BBC/PBS series and Robert Downey, Jr. in two theatrical movies and a third one to come—the seventy-six-year-old Ian McKellen brings a totally new approach to the famous character. Clearly, McKellen is presenting a new version of, a new insight into, Holmes, not one necessitated by disguise or make-up, a key element in the younger man’s solution of crimes, but by adapting to the unavoidable state of this actor’s “mature years.” He is, however, made to look his best in the many flashbacks to Holmes’ earlier days, though make-up is still required to convey the detective at ninety-three.

And Mr. Holmes is, after all, a one-man show for McKellen. He is not only the central figure of the movie, required by plot and theme to fill most of the screen time, but he dominates—instinctively, with his own quiet charisma and sheer presence, and without histrionics. He takes subtle control, as his performances in Shakespeare have shown, calmly and confidently, feeling unthreatened by his co-stars.

In the whole course of the film, not a shot is fired, there are no pyrotechnic explosions, no car chases, no foul language, no jarring special effects, i.e., people flying through the air and doing somersaults. It’s a wonderful change, a relief, an escape—and for a film this good, an experience to be relished.

Director Bill Condon, who had directed McKellen in 1998 in Gods and Monsters, about the last years of English director James Whale, is an American, as is composer Carter Burwell. The artists connected with the writing are also both Americans—Mitch Cullin, whose novel, A Slight Trick of the Mind, is the basis for the film, and Jeffrey Hatcher, the screenwriter. And cinematographer Tobias A. Schliessler is a German.

Director Bill Condon, who had directed McKellen in 1998 in Gods and Monsters, about the last years of English director James Whale, is an American, as is composer Carter Burwell. The artists connected with the writing are also both Americans—Mitch Cullin, whose novel, A Slight Trick of the Mind, is the basis for the film, and Jeffrey Hatcher, the screenwriter. And cinematographer Tobias A. Schliessler is a German.

All that said, Mr. Holmes has a completely British feel, start to finish. The film has all the beautiful scenic backdrops typical of English settings, including the stately Jacobean Hatfield House in Hertfordshire, the luscious Sussex countryside and the famous chalk cliffs, part of the South Downs to where Doyle’s Holmes said he would retire. Most distinctly, it has the slow, methodical, detailed pace of a typical BBC television drama, whether historical or contemporary, as those who watch Poldark or Foyle’s War will sense. This unhurried tempo style is clearly less obvious in Downton Abbey, due to ultra-interesting characters and well-handled, if often familiar, plot lines.

Further reinforcing the English quality and mood of it all, the cast is practically all British, with faces familiar to anyone who watches much BBC or PBS television. Actor-director Philip Davis, who plays Inspector Gilbert in Mr. Holmes, is currently appearing in the Poldark series. Seen as Mycroft Holmes in a flashback, John Sessions seems typecast in a number of mysteries and has several Holmesian connections besides—as Professor Joseph Bell (a real-life doctor who supposedly inspired Doyle’s detective) in Reichenbach Falls, as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in Mr. Selfridge and even in an episode of Cumberbatch’s hit series Sherlock.

Further reinforcing the English quality and mood of it all, the cast is practically all British, with faces familiar to anyone who watches much BBC or PBS television. Actor-director Philip Davis, who plays Inspector Gilbert in Mr. Holmes, is currently appearing in the Poldark series. Seen as Mycroft Holmes in a flashback, John Sessions seems typecast in a number of mysteries and has several Holmesian connections besides—as Professor Joseph Bell (a real-life doctor who supposedly inspired Doyle’s detective) in Reichenbach Falls, as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in Mr. Selfridge and even in an episode of Cumberbatch’s hit series Sherlock.

In a part larger, if only slightly, than either of these supporting actors, Frances de la Tour plays spiritualist Madame Schirmer. She is currently Violet Crosby in the ITV comedy Vicious, seen in the U.S. on PBS, and in each episode she visits the flat of a gay couple (McKellen and Derek Jacobi), who spend their time exchanging cruel but hilarious personal barbs. De la Tour also appears in two Harry Potter movies as Madame Maxime.

In an interesting footnote, Nicholas Rowe, who appeared in Young Sherlock Holmes in 1985 as a boy Sherlock, though he was then nineteen, here makes a cameo appearance.

In an interesting footnote, Nicholas Rowe, who appeared in Young Sherlock Holmes in 1985 as a boy Sherlock, though he was then nineteen, here makes a cameo appearance.

A brief word about Carter Burwell’s score. To reaffirm his belief that films today contain too much background music—and he suggests most of his fellow composers feel the same—Burwell writes little music. Mr. Holmes doesn’t need the crutches the medium often supplies other films, to support visual banality or bridge plot and narrative shortcomings. In the opening is an oboe tune suggestive of an English folk song and behind Holmes’ astute dénouement in a scene with a man’s distraught wife is a lovely, lyrical melody—the essential highlights of the score.

It is 1947, twenty years after Dr. Watson has shared with the public the last of his adventures with Holmes, that about Shoscombe Old Place and the human bones found in the furnace of the old church. Holmes has referred to all these stories as “somewhat embellished.” Holmes (McKellen) is sharing his Sussex seaside cottage with his housekeeper, Mrs. Munro (Laura Linney, the only American among the major stars), and her young inquisitive, intelligent son, Roger (Milo Parker), for whom the old man has a growing affection, despite his gruff, independent exterior.

It is 1947, twenty years after Dr. Watson has shared with the public the last of his adventures with Holmes, that about Shoscombe Old Place and the human bones found in the furnace of the old church. Holmes has referred to all these stories as “somewhat embellished.” Holmes (McKellen) is sharing his Sussex seaside cottage with his housekeeper, Mrs. Munro (Laura Linney, the only American among the major stars), and her young inquisitive, intelligent son, Roger (Milo Parker), for whom the old man has a growing affection, despite his gruff, independent exterior.

In the course of the film, Holmes’ mind flashes back repeatedly to the past—and to two stories, interwoven with his present relationship with the two occupants of his new residence. In the first, he is dissatisfied with the last case Watson had “fictionalized,” as Holmes believes, and has decided “to write the story down, as it was, not as Watson made it, get it right before I die,” as the chronicler of their adventures had always “turned me into fiction.” A husband (Patrick Kennedy) has asked Holmes to check on his wife Ann (Hattie Morahan), who can’t accept the deaths of her two prematurely born infants. In the second case/flashback, Mr. Umezaki, a Japanese man (Hiroyuki Sanada), has a grievance because he believes Holmes is responsible for his father abandoning him and his mother for a life in England.

In the present, Holmes, feeling his age and no longer the neat dresser—now more often in a dressing gown—has recently been to Hiroshima, where he observed the destructive power of the recently dropped atomic bomb. In an effort to restore, at least improve, his foggy memory and recall the details of both events from his past, he is experimenting with a jelly based on the prickly ash plant he discovered in Japan. Later, an accident in his lab injures him and puts him in bed. The housekeeper, now having to devote more time to his care, plans to leave when Holmes is better. Her son, enjoying the company of his new-found friend, is displeased with what he regards as an uneducated mother.

In the present, Holmes, feeling his age and no longer the neat dresser—now more often in a dressing gown—has recently been to Hiroshima, where he observed the destructive power of the recently dropped atomic bomb. In an effort to restore, at least improve, his foggy memory and recall the details of both events from his past, he is experimenting with a jelly based on the prickly ash plant he discovered in Japan. Later, an accident in his lab injures him and puts him in bed. The housekeeper, now having to devote more time to his care, plans to leave when Holmes is better. Her son, enjoying the company of his new-found friend, is displeased with what he regards as an uneducated mother.

Holmes’ doctor (Roger Allam, recently Deputy Inspector Fred Thursday in Endeavour on British television) suggests that he record in his diary each incident of amnesia with a dot; toward film’s end, the frequency of the dots has grown from a few to a multitude.

As time passes, Roger helps the old man remember aspects of the first case, and Holmes instructs the lad in the art of beekeeping, equipped with the veiled hat and smoker. “You ever been bitten?” Roger asks. “Strung!” Holmes corrects. “Bees don’t have teeth!”

As time passes, Roger helps the old man remember aspects of the first case, and Holmes instructs the lad in the art of beekeeping, equipped with the veiled hat and smoker. “You ever been bitten?” Roger asks. “Strung!” Holmes corrects. “Bees don’t have teeth!”

From his past, Holmes recalls his long scene with Ann, doing what he does best, solving a case, and here brilliantly. He is uncharacteristically patient and consoling with the lady. He explains and justifies the clues he has garnered from following her around London: why she examined her husband’s will, why she forged his name on checks and cashed them, why she bought poison at a chemist—not to kill her husband, but to commit suicide. After Holmes has apparently convinced Ann to return to her husband, she steps in front of a train.

It is because of Holmes’ error, tragically seeing this only as another case and overlooking the woman’s need for companionship, that he had retired and isolated himself even more than before, taking up beekeeping.

In the detective’s flashback confrontation and resolution with Mr. Umezaki, he explains that his father simply wanted a better life for himself in England and that Holmes had never met him.

In the detective’s flashback confrontation and resolution with Mr. Umezaki, he explains that his father simply wanted a better life for himself in England and that Holmes had never met him.

As for the climax of the film, and in a final return to the present, Roger is found unconscious, having been repeatedly stung, it’s assumed, by the bees. In an unusual, unguarded display—who could say Holmes was deprived of emotion?—he falls to the ground, crying and wailing over the tragedy. While Roger is rushed to the hospital, Mrs. Munro attempts to burn down the apiary. Holmes stops her, realizing Roger’s stings are from a nearby wasps’ nest, which Holmes deduces the boy attempted to destroy and was attacked. Roger recovers. Holmes tells Mrs. Munro that she and Roger will inherit the cottage when he dies and convinces her to remain instead of going off to some unfulfilling job. He will instruct her, he says, in . . . tending the bees.

Imitating a practice he had witnessed while in Hiroshima, Holmes kneels before a circle of stones and, for each, chants the name of a love one who has passed from his life over the years. As the camera pulls back for one last shot in Mr. Holmes, beyond the bend of the jagged seacoast appear the chalk cliffs of the South Downs.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle intended The Last Bow, in 1917, to be the final Sherlock Holmes adventure, but, as before when the public demanded a resurrection following the detective’s death at the Reichenbach falls in The Final Problem, Doyle had to revive his character once again in 1927 in yet another set of stories. In the intervening years, mainly due to the death of his wife, the author had been sidetracked by his fervent interest in Spiritualism, then the rage. His readers can only wonder at the possibilities of an even further life for Sherlock Holmes, were it not for the hoax of Spiritualism, which Doyle never acknowledged as such.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle intended The Last Bow, in 1917, to be the final Sherlock Holmes adventure, but, as before when the public demanded a resurrection following the detective’s death at the Reichenbach falls in The Final Problem, Doyle had to revive his character once again in 1927 in yet another set of stories. In the intervening years, mainly due to the death of his wife, the author had been sidetracked by his fervent interest in Spiritualism, then the rage. His readers can only wonder at the possibilities of an even further life for Sherlock Holmes, were it not for the hoax of Spiritualism, which Doyle never acknowledged as such.

Quite differently, and a windfall for Sherlock Holmes fans, on screen the life of the detective seems unending, and, now, after Cumberbatch and Downey, Ian McKellen has offered yet another, quite different slant on this master detective, one mellowed by old age and failing memory. We will hope for a sequel and wonder what McKellen has to say about that.

Greg, I thoroughly enjoyed you comprehensive review of “Mr Holmes”. My wife and I fell under the spell of both this exceptional film as well as the extraordinary performance of Ian McKellen – what a fine actor he is.