It seemed that no screen sleuth was so sacred in his role that he couldn’t be played by any number of other actors.

It seemed that no screen sleuth was so sacred in his role that he couldn’t be played by any number of other actors.

Whether large or small, when beginning any survey of those innumerable private detective film series of the 1930s and ’40s, it must be remembered that there is that ultimate standard against which all those other sleuths, alive and solving crimes at the same time, fall short. That touchstone, of course, is the Thin Man series, the six films made between 1934 and 1947, starring William Powell, Myrna Loy and, by all means, Asta the wire-haired terrier. Although the subsequent five films never match the initial release, The Thin Man, the secret ingredients—hardly a secret—make the series marvelous fun, durable and undated.

The films are a sparkling combination of mystery, screwball comedy and the snappy pace of director Woody “One-Shot” Van Dyke, who allowed the sometimes quick-fire dialogue exchanges to overlap, in the coming style of Howard Hawks. The often frantic repartee and sexual innuendos exchanged between this sophisticated married couple, Nick and Nora Charles, are new to the screen, and somewhat shocking—all this besides the sheer magic and charisma of the two stars. A less realized secret, the films are released far enough apart, from two to four years over a thirteen-year period, that they are spared overexposure and movie-goers are allowed time to eagerly anticipate the next release.

The following, then, is not a study of the sleuthing and romantic antics of this couple (for an introduction, see “Remembering 1934 and The Thin Man”.), but of some of their contemporary screen sleuths, who, quite differently, are almost all male and unmarried. Established long before in the Sherlock Holmes/Dr. Watson adventures, and continuing with Nick and Nora, most of these detectives have a partner, sometimes comic but often slow on the uptake, all the better to underline the genius of the boss.

The following, then, is not a study of the sleuthing and romantic antics of this couple (for an introduction, see “Remembering 1934 and The Thin Man”.), but of some of their contemporary screen sleuths, who, quite differently, are almost all male and unmarried. Established long before in the Sherlock Holmes/Dr. Watson adventures, and continuing with Nick and Nora, most of these detectives have a partner, sometimes comic but often slow on the uptake, all the better to underline the genius of the boss.

It’s impossible to cover within this short space all the detectives. Any aficionado of the genre can name, easily, at least twenty private eyes and their kin from this period. So where to begin? Alphabetically would be commonplace; by year impractical, as these series are contemporaneous with one another; and from best to worst, or the other way around, is unrealistic, as quality is subjective, though, still, the disparity between the extremes of best and worst is obvious.

Most of the films are classified, then and now, as B movies, secondary productions of their respective studios. They are generally looked down upon by the critics, though not by the average movie-goer, who lap them up as welcomed antidotes to the times, first the Great Depression and then World War II. This is also the era of film noir, light and shadow, a style that only amplifies the appeal of these films. Some of them have more class than others, and production values vary greatly, even within the same series, depending upon a studio’s enthusiasm at the moment, whether in response to a big success or in support of a major-star cast.

Most of the films are classified, then and now, as B movies, secondary productions of their respective studios. They are generally looked down upon by the critics, though not by the average movie-goer, who lap them up as welcomed antidotes to the times, first the Great Depression and then World War II. This is also the era of film noir, light and shadow, a style that only amplifies the appeal of these films. Some of them have more class than others, and production values vary greatly, even within the same series, depending upon a studio’s enthusiasm at the moment, whether in response to a big success or in support of a major-star cast.

So, finally, here is a mere random selection of the more popular and unique from this considerable and diverse array of detectives, gumshoes, sleuths, private eyes and investigators, some who worked with the law, others who worked just a little bit, perhaps . . . outside the law——

THE LONE WOLF

For the first detective study, let’s start—not from near the bottom of quality and success but from near the top. Many of these gumshoes came from the creative minds of pulp mystery writers and Louis Joseph Vance, in 1914, created the Lone Wolf. Among the silent film portrayals of Michael Lanyard, this jewel-thief-turned-detective, are H. B. Warner and Jack Holt (father of Tim in The Magnificent Ambersons and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre).

For the first detective study, let’s start—not from near the bottom of quality and success but from near the top. Many of these gumshoes came from the creative minds of pulp mystery writers and Louis Joseph Vance, in 1914, created the Lone Wolf. Among the silent film portrayals of Michael Lanyard, this jewel-thief-turned-detective, are H. B. Warner and Jack Holt (father of Tim in The Magnificent Ambersons and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre).

In 1935, Melvyn Douglas launches the “official” fourteen or so Wolf sound films. Although he plays the character only once, in The Lone Wolf Returns, it is one, if not the best of the series. His character is blackmailed by some hoods despite his efforts to retire as a criminal. Douglas co-stars with Gail Patrick (The Maltese Falcon), Douglass Dumbrille (Mr. Deeds Goes to Town) and Thurston Hall. Douglas is followed, also in only one film, by Francis Lederer.

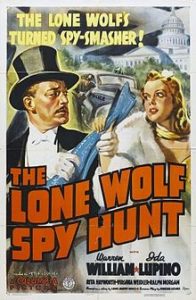

Then Warren William makes the next nine installments, the high-water mark of the series. His first and best is The Lone Wolf Spy Hunt (1939), a rival to Douglas’ effort. Ida Lupino is Lanyard’s zany girlfriend, with Rita Hayworth before she became famous, James Craig and Ralph Morgan as the leader of a spy ring in Washington, D.C. William, tall and slender in stature, is suave and debonair, with a pencil mustache; if he is never mistaken for William Powell, he clearly emulates the persona of that actor.

Then Warren William makes the next nine installments, the high-water mark of the series. His first and best is The Lone Wolf Spy Hunt (1939), a rival to Douglas’ effort. Ida Lupino is Lanyard’s zany girlfriend, with Rita Hayworth before she became famous, James Craig and Ralph Morgan as the leader of a spy ring in Washington, D.C. William, tall and slender in stature, is suave and debonair, with a pencil mustache; if he is never mistaken for William Powell, he clearly emulates the persona of that actor.

If William’s subsequent films are lower-budgeted and less stylish than his first one, they are still thoroughly watchable, and with the next entry, The Lone Wolf Strikes in 1940, Eric Blore begins his tenure as Lanyard’s valet Jamison, offering a comic element along the lines of Hugh Herbert. Jamison also, like his boss, has his connections with a previous life of crime.

Following William’s replacement in 1943 by Gerald Mohr in three mediocre entries, the last Lone Wolf film that comes to the screen is technically outside the series—and a disaster. As a “new” Lone Wolf, Ron Randell destroys the charm of both his character and the series in The Lone Wolf and His Lady (1949).

CHARLIE CHAN

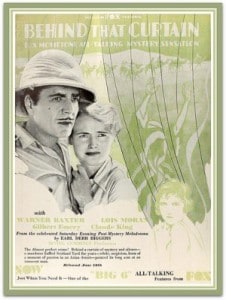

Writer Earl Derr Biggers gets the credit here—for initiating the life of a certain Oriental detective on the Honolulu police force, Charlie Chan. Like the Lone Wolf, Charlie’s film history begins in the silent days. Behind That Curtain (1929), however, represents the first sound appearance of the character, though hardly a “Charlie Chan” film as E. L. Park as the detective appears only in the final minutes. (As a footnote, this film also stars Warner Baxter, relevant here because he later has his own detective series, Crime Doctor, 1943-1949, about a criminal psychologist who, as an amnesia victim, learns he was once a gang leader, a background that helps him in his new life as crime-solver.)

Writer Earl Derr Biggers gets the credit here—for initiating the life of a certain Oriental detective on the Honolulu police force, Charlie Chan. Like the Lone Wolf, Charlie’s film history begins in the silent days. Behind That Curtain (1929), however, represents the first sound appearance of the character, though hardly a “Charlie Chan” film as E. L. Park as the detective appears only in the final minutes. (As a footnote, this film also stars Warner Baxter, relevant here because he later has his own detective series, Crime Doctor, 1943-1949, about a criminal psychologist who, as an amnesia victim, learns he was once a gang leader, a background that helps him in his new life as crime-solver.)

But it isn’t until Warner Oland, in 1931, stars in Charlie Chan Carries On that the series garnered any attention. This and four other films of the period no longer exist, so Oland’s belated introduction for today’s viewers occurs in The Black Camel (1931). Chan travels the world in solving the crimes—from London and Paris to Egypt and Monte Carlo—but in this flick he is on his home turf of Hawaii, aided by an impressive cast: Bela Lugosi, Robert Young, Dwight Frye and even Sherlock Holmes’ Mary Gordon (Mrs. Hudson in the Rathbone/Bruce series).

With Charlie Chan in Paris (1935), the Oland series receives a humanizing injection of family life and father-son humor, in the introduction of Chan’s Number One Son, Lee (Keye Luke). And, as always, there are the wise Chan sayings, as in The Scarlet Clue (1945): “So many fish in fish market, even flower smell same. Much confusion.”

With Charlie Chan in Paris (1935), the Oland series receives a humanizing injection of family life and father-son humor, in the introduction of Chan’s Number One Son, Lee (Keye Luke). And, as always, there are the wise Chan sayings, as in The Scarlet Clue (1945): “So many fish in fish market, even flower smell same. Much confusion.”

When Oland dies in 1937, 20th Century-Fox replaces him with another non-Asian, Sidney Toler—Oland was born in Sweden, Toler in Missouri—who first stars as Chan in Charlie Chan in Honolulu (1938), and assisted, now, by a new, replacement son, Number Two, Jimmy (Sen Yung). Toler is even more convincingly Chinese, and the series continues with good writing and an array of first-class character actors to play criminals and provide red herrings.

When the studio drops the series in 1942, it is taken over, still with Toler, by Monogram Pictures, itself a B studio. The quality and appeal of the films decline considerably. When Toler dies in 1947, he is replaced by Boston-born Roland Winters. In 1949 and Sky Dragon, the Charlie Chan series is declared officially dead, a terrible film to end one of the longest-running and most prolific detective series of the ’30s and ’40s, with over forty films.

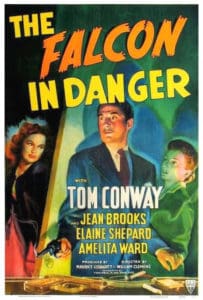

THE FALCON

Like the two previous series, the Falcon has more than one lead actor in the title role, and also has a literary source, in this case Michael Arlen’s stories of the amateur, trouble-shooting sleuth, another ladies’ man in the Michael Lanyard mold. As an exception to the lifetime of most of these detective series, which span the two pivotal decades, the Falcon exists entirely within the ’40s.

Like the two previous series, the Falcon has more than one lead actor in the title role, and also has a literary source, in this case Michael Arlen’s stories of the amateur, trouble-shooting sleuth, another ladies’ man in the Michael Lanyard mold. As an exception to the lifetime of most of these detective series, which span the two pivotal decades, the Falcon exists entirely within the ’40s.

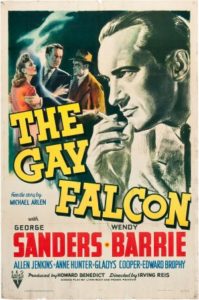

Usually in shady or sardonic roles, George Sanders plays the Falcon in the first four films, beginning in 1941 with The Gay Falcon—“gay” here in the old sense of “happy.” In a film also starring Allen Jenkins, Gladys Cooper and Arthur Shields, the detective breaks up a jewelry insurance scam.

As something of a distinctive gimmick, in several of the films a luscious young lady appears toward the end to threaten the Falcon with some kind of danger or provide a problem—murder, theft, riddle—which becomes the plot of the next film.

The series does showcase the cream of supporting actors, the likes of Edward Brophy, James Gleason, Ward Bond, Hans Conried and the perennial neurotic crook, Elisha Cook, Jr. (most famously in The Maltese Falcon and The Big Sleep). Here, too, appear some young, aspiring actresses, among them Wendy Barrie and Harriet Nelson, and at least two stars who would later find greater fame in essentially the same genre—Jane Greer in a landmark crime film noir, Out of the Past, and Barbara Hale in the Perry Mason TV series.

In 1942, Sanders departs the series, not because of death, so often the case in the Chan movies, but simply because he wants out. Uniquely, he is replaced by his “brother” from the script, Sanders’ actual brother, Tom Conway. Conway persists for nine episodes until John Calvert succeeds him in the final three forgettable entries. A sad demise for a series that had first offered such potential in the performances of Sanders.

In 1942, Sanders departs the series, not because of death, so often the case in the Chan movies, but simply because he wants out. Uniquely, he is replaced by his “brother” from the script, Sanders’ actual brother, Tom Conway. Conway persists for nine episodes until John Calvert succeeds him in the final three forgettable entries. A sad demise for a series that had first offered such potential in the performances of Sanders.

BOSTON BLACKIE

The Boston Blackie series flourishes during the same years, 1941-1949, as the Falcon, but unlike most of the detective films in this genre, the sleuth is played by the same actor the entire time. Chester Morris also portrays a reformed thief. His manner, however, is carefree and spontaneous, as if nothing bothers him and there’s no situation from which he cannot escape—and a sneer for any criminal who connives against him.

He is aided, taunted and delighted, as the case may be, by the standard regulars—the talkative, obtuse buddy “the Runt” (George E. Stone); the police detective, Inspector Faraday (Richard Lane), suspicious of Blackie’s motives and criminal background; and the irresponsible millionaire Arthur Manleder (the always delight Lloyd Corrigan).

Some of the films are guided by first-class directors—William Castle, Robert Florey and Edward Dmytryk, among others, Castle in particular struggling at this time to find his stride. The first of the fourteen films, Meet Boston Blackie (1941), if only an hour, is a great début for the series, with Franz Planer’s (Roman Holiday, Breakfast at Tiffany’s) chic cinematography and Florey’s stylish direction. Blackie is after spies on Coney Island, a nimble-quick blend of comedy, mystery and almost tongue-in-cheek sleuthing.

In a few of the episodes, Morris’ skill as a magician is worked into the scripts. In both Alias Boston Blackie (1942) and Boston Blackie and the Law (1946), Blackie demonstrates his skill at prestidigitation in a prison. The first movie features Larry Parks and a brief shot of Lloyd Bridges as a bus driver. If neither of these installments is outstanding, they are thoroughly adequate for their type of film.

In a few of the episodes, Morris’ skill as a magician is worked into the scripts. In both Alias Boston Blackie (1942) and Boston Blackie and the Law (1946), Blackie demonstrates his skill at prestidigitation in a prison. The first movie features Larry Parks and a brief shot of Lloyd Bridges as a bus driver. If neither of these installments is outstanding, they are thoroughly adequate for their type of film.

By contrast, Boston Blackie Goes Hollywood (1942), with a supporting cast that includes a young Forrest Tucker, is a notch or two above most in the series. The police follow Blackie on his way to California with $60,000, hoping he will lead them to the lost Monterey Diamond.

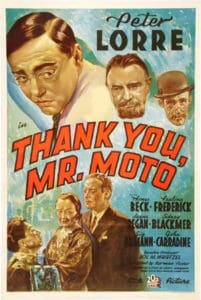

MR. MOTO

Although another Asian sleuth, Mr. Moto, now Japanese, appears in only nine films, a relative small number compared with most in the genre, the series makes quite an impression between 1937 and 1939, thanks to the charisma and ideal casting of Peter Lorre.

Although another Asian sleuth, Mr. Moto, now Japanese, appears in only nine films, a relative small number compared with most in the genre, the series makes quite an impression between 1937 and 1939, thanks to the charisma and ideal casting of Peter Lorre.

The same studio, 20th Century-Fox, that produced the Charlie Chan films made these as well, however much the duality seems at cross-purposes. If Mr. Moto lacks a helper with whom to exchange barbs and insights or the familial touch of Chan and his various sons, the Lorre series has superior production values and some of the finest supporting players of any detective series. Only a partial list includes Sig Rumann, Jean Hersholt, Lionel Atwill, John Carradine, Joseph Schildkraut, Ricardo Cortez, Robert Coote, Sidney Blackmer, Leon Ames, Henry Wilcoxon and even George Sanders in Mr. Moto’s Last Warning (1939), this before his stint as the Falcon.

Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937) is considered by many to be the best of the series. Strange, as in this case, how often the better films come early in a series’ history. In this movie, as an example of the exotic settings and the often ridiculous plots (who really cares?), Mr. Moto is on the trail of the hidden treasure of Genghis Khan, supposedly revealed in seven ancient scrolls. In the last entry in the series, Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation (1939), the detective is in search of the crown of the Queen of Sheba.

Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937) is considered by many to be the best of the series. Strange, as in this case, how often the better films come early in a series’ history. In this movie, as an example of the exotic settings and the often ridiculous plots (who really cares?), Mr. Moto is on the trail of the hidden treasure of Genghis Khan, supposedly revealed in seven ancient scrolls. In the last entry in the series, Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation (1939), the detective is in search of the crown of the Queen of Sheba.

Like Chan, Moto is a globetrotter, and no place is too far flung, or too inaccessible, for his cool, often crafty investigating, whether the Suez Canal, Puerto Rico, the jungles of Indochina or Shanghai. Often employing a disguise to catch his man, his simple Oriental makeup consists of a pair of round prop eyeglasses.

20th Century-Fox, as late as 1965, thinks it can revive the series with The Return of Mr. Moto. With Henry Silva miscast as Moto and a supporting cast of third-stringers, it is a dismal, lifeless exercise, possessing none of the charm of the originals.

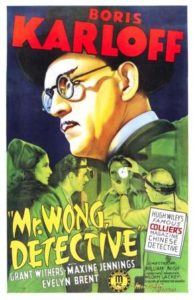

There is still a third Asian detective (maybe more?), Mr. Wong, in a five-film series produced by the Poverty Row studio Monogram Pictures between 1938 and 1940. The production values are abysmal, with too much dialogue and two badly scripted crime-fighting companions for Wong, an unappealing police captain (Grant Withers) and an insufferable lady newspaper reporter (Marjorie Reynolds). The only saving grace of the films is Boris Karloff as Wong. The wonder is why Karloff, who, yes, made more than his share of poor pictures in his career, ever agreed to such a dead-end venture.

There is still a third Asian detective (maybe more?), Mr. Wong, in a five-film series produced by the Poverty Row studio Monogram Pictures between 1938 and 1940. The production values are abysmal, with too much dialogue and two badly scripted crime-fighting companions for Wong, an unappealing police captain (Grant Withers) and an insufferable lady newspaper reporter (Marjorie Reynolds). The only saving grace of the films is Boris Karloff as Wong. The wonder is why Karloff, who, yes, made more than his share of poor pictures in his career, ever agreed to such a dead-end venture.

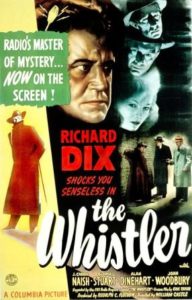

THE WHISTLER

To conclude this all too-brief survey of these ’30s and ’40s detective series, it’s tempting to return to a Lone Wolf-style series like Philo Vance. That would suitably complement that initial detective, but for the sake of variety and for a quirky departure from the usual, there are the eight Whistler films, starring Richard Dix in all but the last, which stars Michael Duane. One of the shortest spans of any of its counterparts, the series runs 1944-1948.

These movies offer at least two distinctions. For one, Dix changes characters, film to film, playing either a hero or a villain. In the initial entry, The Whistler (1944), he spends his time trying to cancel a contract he has taken out on his own life. In Mark of the Whistler (1945), Dix is a drifter who pretends to be the long-lost owner of a dormant bank account. He is a detective all right in The Mysterious Intruder (1946), but he commits murder to secure some rare Jenny Lind wax recordings. Dix ranges from an insane artist in Secret of the Whistler (1946) to a cultured amnesiac helped by a fortune teller to regain his memory in The Power of the Whistler (1945).

These movies offer at least two distinctions. For one, Dix changes characters, film to film, playing either a hero or a villain. In the initial entry, The Whistler (1944), he spends his time trying to cancel a contract he has taken out on his own life. In Mark of the Whistler (1945), Dix is a drifter who pretends to be the long-lost owner of a dormant bank account. He is a detective all right in The Mysterious Intruder (1946), but he commits murder to secure some rare Jenny Lind wax recordings. Dix ranges from an insane artist in Secret of the Whistler (1946) to a cultured amnesiac helped by a fortune teller to regain his memory in The Power of the Whistler (1945).

A second feature peculiar to this series is the use of a mysterious stranger whistling a tune as he walks along. “I am the Whistler,” he says, “and I know many things, for I walk by night.” (The whistling is provided by Dorothy Roberts, to a tune by Wilbur Hatch, backed by an orchestra.) An unseen narrator (Otto Forrest) introduces each film; his voice is sometimes heard to bridge scenes, or, on other occasions, the Whistler’s presence is linked to the whistling or to a walking shadow on the wall.

The series has its share of good directors (William Castle on four occasions), engrossing scripts with ironic twists and more than able supporting players. The Whistler radio program which begins before the film series and continues after it until 1955, stars Bill Forman most often in the title role and Marvin Miller as the narrator.

—————————————————-

There are, of course, many other detective series which have been omitted here. Despite the efforts of, again, Warren William as a detective, this time in four of six Perry Mason films, 1934-1937, Warner Bros. changes the portrayal of the sleuth, film to film, so Perry Mason would only be adequately realized with the coming of Raymond Burr and TV.

There are, of course, many other detective series which have been omitted here. Despite the efforts of, again, Warren William as a detective, this time in four of six Perry Mason films, 1934-1937, Warner Bros. changes the portrayal of the sleuth, film to film, so Perry Mason would only be adequately realized with the coming of Raymond Burr and TV.

Although the Ellery Queen novels were then and are now highly successful, the related series is one of the weakest seen on the screen; the casting of Ralph Bellamy proves ill-advised, as the actor plays the character as an idiot. The exploits of a rare female detective, Hildegarde Withers, runs 1932-1937, initially starring the elderly character actress Edna May Oliver until she unfortunately leaves the series. Other detectives given a series include Bulldog Drummond, the Saint, Dick Tracy, Michael Shayne, Nick Carter and Torchy Blane.

—————————————————-

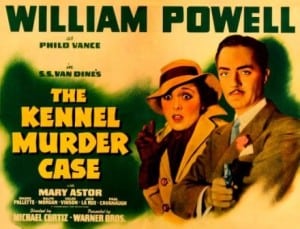

A brief footnote about Philo Vance seems necessary after all. The series is distinctive in several ways. It has extraordinarily chic mysteries, were made over almost twenty years, produced by several different studios and feature various actors in the lead role, including Warren William, Basil Rathbone and, most memorably, William Powell.

Filmed by Warner Bros., The Kennel Murder Case (1933) must be mentioned as possibly—well, let it be said: almost certainly—more sophisticated, more interesting and more original than any series, individual film or actor in any role highlighted in this survey. The film stars, as Philo, William Powell (he made four in the series), Mary Astor, Eugene Pallette as the harassed Detective Heath, Paul Cavanagh, Ralph Morgan as the killer and—not to be forgotten—the terrier at the dog show, Asta, before his star status in the Thin Man series.

Filmed by Warner Bros., The Kennel Murder Case (1933) must be mentioned as possibly—well, let it be said: almost certainly—more sophisticated, more interesting and more original than any series, individual film or actor in any role highlighted in this survey. The film stars, as Philo, William Powell (he made four in the series), Mary Astor, Eugene Pallette as the harassed Detective Heath, Paul Cavanagh, Ralph Morgan as the killer and—not to be forgotten—the terrier at the dog show, Asta, before his star status in the Thin Man series.

Here, in this film, is the old cliché of a dead man (Robert Barrat) found in a locked room. Philo, through instinct and a discerning eye, deduces that the supposed suicide is a murder victim. Toward film’s end, in a dénouement just before the killer’s disclosure, Philo reveals that, first, Barrat had sat in his easy chair, unaware he had been stabbed. He dies. Having seen his victim earlier at a window, the killer returns to finish the job. Before he can arrive, however, a third party sneaks in and shoots the “sleeping” Barrat and makes it appear a suicide, craftily securing the inside door latch from outside. Now the original killer returns to the house, and in the dark mistakes the departing third party for Barrat and kills him. Got that?! And in the pièce de résistance—yes, there’s still more, a stunning climax—Philo sets a trap for the killer, using another dog to identify him.

Tautly directed by Michael Curtiz, The Kennel Murder Case. is wonderfully atmospheric, convoluted and slick, a tour de force, with Powell never better, one of the great detective films of these early B&Ws.