From a legendary film critic and movie fan extraordinaire,here is the highlights reel of a life spent at the movies.

When a skilled writer such as Richard Schickel publishes yet another book—there are twenty-three listed in his latest, but he himself infers there’re more—what further praise can be said about his writing ease and spontaneity that hasn’t already been said? And self-evident is his enthusiasm for this art he so vividly discusses—and movies are an art, after all, he says rather early on.

His latest book, Keepers, The Greatest Films—and Personal Favorites—of a Moviegoing Lifetime, represents almost eighty years of movie-watching, movie-reviewing and, now, movie-reminiscing about some of those films he has seen. Schickel warns, however, against too fervent an attachment to motion pictures: “Where once we did not take movies seriously enough, we now, I think, oftentimes take them too seriously . . . Movies are, in some sense, nothing—a pastime, an evening’s entertainment. And yet they are, for quite a few of us, everything: well, almost everything.”

Also a film historian and TV documentarian, the author, now eighty-two, seems to pinpoint the essence of an idea in a few succinct words, and writes in a relaxed, natural, conversational style. The book is roughly in chronological order, but relaxed enough to be spontaneous and to allow for, at times, an almost string-of-consciousness flow. In the same vein, Schickel is unconcerned that, say, a director’s films are covered out of order throughout the book, and is unapologetic, correctly so, that he returns to second chapters on Eastwood and Kubrick, among his favorite directors.

Suggestive of this chronology, Schickel starts with the silent movies, making comparisons between, in his opinion, the two greatest stars, Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. If it came to a mandatory preference, he would choose Keaton. “And there is a quiet brilliance about his work as a filmmaker, a reluctance to sell it out for a quick gag . . . , that Chaplin does not quite match.”

Suggestive of this chronology, Schickel starts with the silent movies, making comparisons between, in his opinion, the two greatest stars, Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. If it came to a mandatory preference, he would choose Keaton. “And there is a quiet brilliance about his work as a filmmaker, a reluctance to sell it out for a quick gag . . . , that Chaplin does not quite match.”

The first movie Schickel ever saw was Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and, at four years old, it’s assumed he didn’t review it. He implies that Pinocchio, which premiered four years after Dwarfs, and failed, at the time, to earn back its investment, was “the first great movie I ever saw, though I didn’t know it at the time.”

Good films and bad films. Of the 22,250 movies Schickel estimates he’s seen in his lifetime, “Not many of them were pleasurable at any level, but you learn as much about film from the bad ones as you do from the good ones.” Schickel quotes W. H. Auden’s reference to the phenomenon of so few masterpieces in art as the “High Holidays of the Spirit,” and equates Auden with his own thought: “We need the routine, the merely all right, if only as a benchmark against which to measure the extraordinary when it happens along.” As King Vidor said, if he had anticipated the attention given to his early films—he directed Rudolph Valentino in many pictures—“he would have made them better.”

All of Schickel’s chapters are brief, maybe not as brief as novelist James Patterson’s, and under the title “Greatness,” the critic seems to sum up the dilemma of good and bad movies, correctly so for many people who believe as he does, that “ . . . that period between 1935 and the onset of World War II was the greatest era in the history of American movies.”

The author somehow qualifies the comment by oddly saying he is probably in the midst of making it, as if it had just occurred to him, or as if this observation is something of a revelation to the world. “A few years back there was talk about—even a book or two—dubbing 1939 the movies’ greatest year. I’m okay with that—the case can be made, not that it makes much difference.”

The author somehow qualifies the comment by oddly saying he is probably in the midst of making it, as if it had just occurred to him, or as if this observation is something of a revelation to the world. “A few years back there was talk about—even a book or two—dubbing 1939 the movies’ greatest year. I’m okay with that—the case can be made, not that it makes much difference.”

While not necessarily suggesting an extension of this “High Holiday of the Spirit” of the late ’30s, this writer would add a proviso, that many of the movies during much of the ’40s shed a respectable afterglow to those previous years, before, indeed, the falling off seriously began the following decade. “Good movies,” Schickel writes, “are made all the time—though not as often as bad ones,” though, equally true, and sadly, even less often now.

Of Schickel’s TV documentaries, the most enterprising and extensive is The Men Who Made the Movies, which originally aired on PBS, for eight consecutive nights in November and December of 1973. (An informative booklet was even mailed to viewers upon request.) Each hour-long installment profiled a single director—with an interview, a personal history and film clips from the best-known films. The featured directors, then all alive and many still working, have since died: Raoul Walsh, Frank Capra, Howard Hawks, King Vidor, George Cukor, William Wellman, Alfred Hitchcock and Vincente Minnelli. Capra was the last to pass on, in 1991, the longest lived at ninety-four.

Although Sch ickel admits to preferring American films over foreign, he renders due respect to François Truffaut, Ingmar Bergman, Satyajit Ray, Federico Fellini, Sergio Leone and Werner Herzog. While the writer does muster a good deal of enthusiasm for these subjects, his heart seems elsewhere. He admits, in fact: “ . . . I am more comfortable, more authoritative, with American movies.”

ickel admits to preferring American films over foreign, he renders due respect to François Truffaut, Ingmar Bergman, Satyajit Ray, Federico Fellini, Sergio Leone and Werner Herzog. While the writer does muster a good deal of enthusiasm for these subjects, his heart seems elsewhere. He admits, in fact: “ . . . I am more comfortable, more authoritative, with American movies.”

When encountering a writer as knowledgeable and expressive as Richard Schickel, it’s often the best policy to quote his thoughts, or, having written this much, to continue quoting them. What better clue to the tone and depth of a book? Some of his evaluations agree with the established consensus, others may contradict the mainstream, even occasionally violate, in particular, the accepted milestone movies.

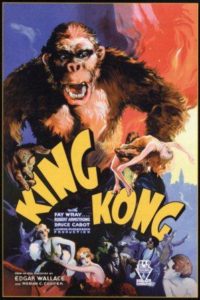

“I think [King Kong] is one of the greatest works in the history of popular culture, for a lot of reasons. Most important, it is wholly original. . . . Indeed, though it has plenty of scary sequences, it is not really a horror movie at all; it is, if you will, a romance, the story of the greatest misalliance in the history of movies.”

While initially stating that Orson Welles’ first film is the greatest movie ever made, in the next paragraph he seems to question himself, or is it an excuse to expound, or is he planting a seed for those who still have doubts about the movie’s status? “Is Citizen Kane really the best film ever made? You would get some arguments about that in foreign territories, I imagine. I think to some degree we are still playing catch-up ball with Kane. It is surely better than How Green Was My Valley, which won the best-picture Oscar that year . . . ”

While initially stating that Orson Welles’ first film is the greatest movie ever made, in the next paragraph he seems to question himself, or is it an excuse to expound, or is he planting a seed for those who still have doubts about the movie’s status? “Is Citizen Kane really the best film ever made? You would get some arguments about that in foreign territories, I imagine. I think to some degree we are still playing catch-up ball with Kane. It is surely better than How Green Was My Valley, which won the best-picture Oscar that year . . . ”

Another accepted “great” movie also fares less well with Schickel. Here he is more direct: “Gone With the Wind seems to me a faux epic—a great movie because its producer, David O. Selznick, kept insisting it was. . . . I think I might have liked it better if Bette Davis had played Scarlett O’Hara. It needs her kind of lunacy to work. Vivien Leigh is too kittenish for my taste, too intent on ingratiating herself with the audience.” Schickel does give readers, and lovers of the film and Leigh, something to think about.

Humor and wit are used sparingly in Keepers. If the author is enthusiastic about this art, he is also deadly serious about it most of the time. There was humor, however, for a thirteen-year-old whose classroom assignment was to see Laurence Olivier’s Henry V in 1946. Being quite impressed with his comprehension and appreciation of the “high-toned palaver,” he did notice a mistake. “There is a big old hell-for-leather cavalry charge . . . [and] down this valley Olivier’s horsemen splendidly thunder—right past a whole bunch of power lines. Yikes! How come Olivier didn’t notice them? Or maybe he did and was locked into his sequence and couldn’t move his horses and men elsewhere . . . I was naturally pleased with myself, being so observant. What adolescent does not like to see adults screwing up?”

Humor and wit are used sparingly in Keepers. If the author is enthusiastic about this art, he is also deadly serious about it most of the time. There was humor, however, for a thirteen-year-old whose classroom assignment was to see Laurence Olivier’s Henry V in 1946. Being quite impressed with his comprehension and appreciation of the “high-toned palaver,” he did notice a mistake. “There is a big old hell-for-leather cavalry charge . . . [and] down this valley Olivier’s horsemen splendidly thunder—right past a whole bunch of power lines. Yikes! How come Olivier didn’t notice them? Or maybe he did and was locked into his sequence and couldn’t move his horses and men elsewhere . . . I was naturally pleased with myself, being so observant. What adolescent does not like to see adults screwing up?”

Schickel’s praise of one actor in particular is totally justified and, in some ways, long overdue for many who have taken him for granted. “[Claude] Rains had one of the most flexible and elegant voices in the history of the cinema. . . . and [I] propose that Rains may be the best character actor in the history of the movies. . . . He was slight of stature, so he could never aspire to the heroic. He acted prodigiously, relentlessly, effortlessly, and his range was astounding. He never gave a bad performance.”

By way of an introduction to Alfred Hitchcock, Schickel mentions one of the director’s most famous lines—no, not the one about “actors are cattle”! When Ingrid Bergman asked Hitchcock how she should play a certain scene, he admonished her for her concern and warned, “It’s only a movie, Ingrid.” “I came to know Hitch in his later years,” the author writes, “and I am here to testify that no man ever took movies more seriously than he did. That is true of almost everyone who has spent his life, cynically or idealistically, in their service.”

By way of an introduction to Alfred Hitchcock, Schickel mentions one of the director’s most famous lines—no, not the one about “actors are cattle”! When Ingrid Bergman asked Hitchcock how she should play a certain scene, he admonished her for her concern and warned, “It’s only a movie, Ingrid.” “I came to know Hitch in his later years,” the author writes, “and I am here to testify that no man ever took movies more seriously than he did. That is true of almost everyone who has spent his life, cynically or idealistically, in their service.”

Well, Richard Schickel’s enthusiasm for films, demonstrated so vividly in the pages of Keepers, shows itself to be right up there with Hitchcock’s. No doubt about it. And if a reader’s interest in the movies, heaven forbid!, should be only a casual or even an uninterested one, he should be careful: Schickel’s passion may well be catching. Above all, this is a reading pleasure for, oh, let’s say, People Who Love the Movies.