“The werewolf is neither man nor wolf, but a satanic creature with the worst qualities of both.” —— Dr. Yogami (Warner Oland) to Dr. Glendon (Henry Hull)

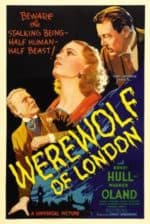

If nothing else, for it isn’t all that great a horror movie as horror flicks go, The Werewolf of London established any number of fallacies about werewolves that would be perpetuated in most subsequent movies featuring humans afflicted with lycanthropy, including that the condition can be “caught” by the bite of a werewolf and that the condition can be reawakened by the moon.

This was the first in a long string of werewolf films from Universal Pictures, the studio getting its foot in the door from the first as the master, or, sometimes, less than a master, of this special corner in the crypt of the horror genre.

What if, in The Werewolf of London, the lycanthropy facts don’t jive with actual legend. What if the plot creaks at times, that the special effects are less sophisticated than in two recent Universal efforts, say, Frankenstein (1931) and The Invisible Man (1934). What if Spring Byington, one of only two Americans among the major players, is miscast, her speech and flighty behavior a bit incongruous with the London setting and the British accents.

Rather enjoy what there is to enjoy in The Werewolf of London. The other American, Henry Hull, with unflattering, close-cut hair (perhaps to facilitate the heavy make-up), renders a convincing, sincere performance as the scientist unable to overcome those nocturnal compulsions. Valerie Hobson, his twenty-seven-years-younger wife, is radiant on screen and ably conveys the frustrations of an unhappy marriage, for she wants to understand what it is that draws her husband away from her.

Although many of the stalwarts among the Universal horror thespians are absent here—E. E. Clive, Una O’Connor, John Carradine, Dwight Frye, Edward Van Sloan and Lionel Atwill—some lesser known character actors of that studio provide ample support. For instance, the burgomaster/mayor in Son of Frankenstein (1939) and The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), Lawrence Grant, serves now in a somewhat less obscure role as Sir Thomas Forsythe, chief of police. J. M. Kerrigan, the police chief after Claude Rains in Universal’s The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1935), and bit player in a hundred other films, including the non-Universal Gone With the Wind (1939), Mr. Lucky (1943) and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), is Hull’s lab assistant.

Although many of the stalwarts among the Universal horror thespians are absent here—E. E. Clive, Una O’Connor, John Carradine, Dwight Frye, Edward Van Sloan and Lionel Atwill—some lesser known character actors of that studio provide ample support. For instance, the burgomaster/mayor in Son of Frankenstein (1939) and The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), Lawrence Grant, serves now in a somewhat less obscure role as Sir Thomas Forsythe, chief of police. J. M. Kerrigan, the police chief after Claude Rains in Universal’s The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1935), and bit player in a hundred other films, including the non-Universal Gone With the Wind (1939), Mr. Lucky (1943) and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), is Hull’s lab assistant.

And, as to that adaptation of Charles Dickens’ unfinished last novel about Edwin Drood, the film at hand is enliven by some comic relief from two old-lady actresses who had appeared together in the Rains movie. In The Werewolf of London, Zeffie Tilbury is now the landlady Mrs. Moncaster and Ethel Griffies her hotel boarder Mrs. Whack. That last name well suggests the mirth in their conversations and imbibings. Cackling together during a meal, Mrs. Whack thinks her food tastes peculiar until Mrs. Moncaster points out that part of her hat veil is in her mouth.

The two ladies assume the mischief of the absent O’Connor, their antics a highlight of the film to many viewers. When Hull comes to the hotel for a room where a locked door will, he thinks, confine him during that night’s hairy conversion, he rents from Mrs. Moncaster. As she shows him to his room, he asks, “What would you say if I were to tell you it was possible for a man to turn into a werewolf?” (A rather blatant statement considering his efforts to keep his problem a secret!) “I’d say,” she laughs, “I was Little Red Riding Hood!,” and finger pokes him in the chest.

The two ladies assume the mischief of the absent O’Connor, their antics a highlight of the film to many viewers. When Hull comes to the hotel for a room where a locked door will, he thinks, confine him during that night’s hairy conversion, he rents from Mrs. Moncaster. As she shows him to his room, he asks, “What would you say if I were to tell you it was possible for a man to turn into a werewolf?” (A rather blatant statement considering his efforts to keep his problem a secret!) “I’d say,” she laughs, “I was Little Red Riding Hood!,” and finger pokes him in the chest.

Henry Hull insisted that Jack Pierce’s original werewolf make-up be toned down, mainly because its application was time-consuming and its appearance excessively bizarre and zombie-like. In one of the wolf transformation scenes not using time-lapse photography, Hull passes several columns, each time becoming more wolf-like. It was a dollying/editing trick used in “The Howling Man,” a 1960 TV episode of Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone, about the Devil locked in a cell and released by a gullible stranger. The Devil is played by Robin Hughes and Brother Jerome, who had warned of the prisoner’s identity, is none other than John Carradine. Small world!

The music score is screen-credited to Karl Hajos, who, like the film’s cinematographer, Charles Stumar, was born in Budapest and died in California. The music is not by Hajos; he is only the conductor. Much of the score, mainly during Hull’s wolfizing, is stock material by Heinz Roemheld, in particular, from The Black Cat (1933) and The Invisible Man. Borrowed classical music includes that old standby of the time, Franz Liszt’s Les Préludes. For source music, it’s Johann Strauss, Jr.’s Tales from the Vienna Woods, heard at a garden party, and an aria (terribly sung by Eole Galli) from Irish composer Vincent Wallace’s obscure 1845 opera Maritana during Byington’s salon gathering.

The music score is screen-credited to Karl Hajos, who, like the film’s cinematographer, Charles Stumar, was born in Budapest and died in California. The music is not by Hajos; he is only the conductor. Much of the score, mainly during Hull’s wolfizing, is stock material by Heinz Roemheld, in particular, from The Black Cat (1933) and The Invisible Man. Borrowed classical music includes that old standby of the time, Franz Liszt’s Les Préludes. For source music, it’s Johann Strauss, Jr.’s Tales from the Vienna Woods, heard at a garden party, and an aria (terribly sung by Eole Galli) from Irish composer Vincent Wallace’s obscure 1845 opera Maritana during Byington’s salon gathering.

The Werewolf of London opens, not in London, but in Tibet. Dr. Wilfred Glendon (Hull), an English botanist, and his assistant, Hugh Renwick (Clark Williams), are searching for the mariphasa plant, which is said to take life from the moon. A local priest (Egon Brecher, the majordomo in The Black Cat) warns him, somewhat blandly—and ungrammatically: “There are some things it is better not to bother with.” (Claude Rains said it somewhat better on his deathbed in The Invisible Man: “I meddled in things . . . that man must leave alone,” advice Dr. Glendon should have taken.)

The Werewolf of London opens, not in London, but in Tibet. Dr. Wilfred Glendon (Hull), an English botanist, and his assistant, Hugh Renwick (Clark Williams), are searching for the mariphasa plant, which is said to take life from the moon. A local priest (Egon Brecher, the majordomo in The Black Cat) warns him, somewhat blandly—and ungrammatically: “There are some things it is better not to bother with.” (Claude Rains said it somewhat better on his deathbed in The Invisible Man: “I meddled in things . . . that man must leave alone,” advice Dr. Glendon should have taken.)

Glendon is bitten by a strange creature which has all the appearance of—sure enough!—a werewolf, but the botanist does find a mariphasa plant and takes it back to his lab in London.

At a garden party, Glendon’s wife, Lisa (Hobson), meets Paul (Lester Matthews), a childhood sweetheart, who, while pursing Lisa, will later warn a skeptical Sir Forsythe of the existence of werewolves. Glendon meets at the gathering another botanist, Dr. Yogami (Warner Oland, better known as Charlie Chan in the detective series), who says the two had met in Tibet, although Glendon doesn’t remember. When Yogami mentions lycanthropy, that there are two incidences of werewolves in London, Glendon suggests that secretions from the mariphasa can provide a temporary antidote for the affliction. So far, his lab tests, he says, have been negative.

One night, Glendon first experiences a symptom of lycanthropy. His hand begins to grow animal hair, apparently induced by the rays of his moon lamp, which he is using to stimulate the mariphasa to bloom. He chases out his assistant Hawkins (Kerrigan) before he can see anything, but, to his amazement, he finds that a drop of the dew from the blossom reverses the change.

One night, Glendon first experiences a symptom of lycanthropy. His hand begins to grow animal hair, apparently induced by the rays of his moon lamp, which he is using to stimulate the mariphasa to bloom. He chases out his assistant Hawkins (Kerrigan) before he can see anything, but, to his amazement, he finds that a drop of the dew from the blossom reverses the change.

Later, Yogami warns, “The werewolf instinctively seeks to kill the thing it loves best.” That same night, Glendon reads in an old manuscript that unless the mariphasa is regularly applied, the werewolf “must kill at least one human each night of the full moon or become permanently afflicted.” As he is reading, Yogami steals two blossoms from the plant.

While the snooty Miss Ettie Coombes (Byington) is holding a soirée, she commits a faux pas in her attempt to impress Sir Forsythe’s wife (Charlotte Granville). Commenting on the evening’s singer, Coombes says, “She sings Botticelli divinely.” The other lady replies, “One doesn’t sing Botticelli, one paints him.” Then Coombes proceeds to introduce Dr. Yogami as “Dr. Yokohama.”

While the snooty Miss Ettie Coombes (Byington) is holding a soirée, she commits a faux pas in her attempt to impress Sir Forsythe’s wife (Charlotte Granville). Commenting on the evening’s singer, Coombes says, “She sings Botticelli divinely.” The other lady replies, “One doesn’t sing Botticelli, one paints him.” Then Coombes proceeds to introduce Dr. Yogami as “Dr. Yokohama.”

When Glendon discovers the blossoms missing, and now transformed into a werewolf, he crashes Coombes’ gathering. He fails in his attempt to kill her—the lady’s scream is really too much—and flees, killing instead a woman in the street. Another woman dies the next night, after he crashes again, now through the window of the hotel room he had taken to restrict his nocturnal prowls.

When Glendon realizes it was Yogami who attacked and bit him in Tibet, for he is also a werewolf, he kills him. Later, in an attempt to kill Lisa, almost fulfilling Yogami’s prophecy that a werewolf “kills the thing he loves best,” he is shot by a policeman.

When Glendon realizes it was Yogami who attacked and bit him in Tibet, for he is also a werewolf, he kills him. Later, in an attempt to kill Lisa, almost fulfilling Yogami’s prophecy that a werewolf “kills the thing he loves best,” he is shot by a policeman.

As he is dying, at the foot of the stairs where he has fallen from the bullet, he confesses, “Thanks for the bullet. It was the only way. In a few moments now, I shall know why all of this had to be. Lisa, goodbye. . . . I’m sorry.” Through time lapse photography, he gradually changes from wolf back to human again.

Saw this movie a couple of weeks ago. Thought it was pretty good.