“She was a charming middle-aged lady with a face like a bucket of mud. I gave her a drink. She was a gal who’d take a drink, if she had to knock you down to get the bottle.” —a sample of Philip Marlowe’s narration

“She was a charming middle-aged lady with a face like a bucket of mud. I gave her a drink. She was a gal who’d take a drink, if she had to knock you down to get the bottle.” —a sample of Philip Marlowe’s narration

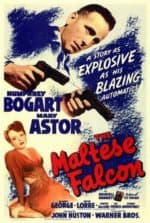

Imagine Humphrey Bogart’s 1941 The Maltese Falcon with Raymond Chandler’s sardonic, hard-boiled narration, with the similes, metonyms and personifications, and you have another classic, almost as good. Murder, My Sweet (1944) may not have Bogart as Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade, but it has Dick Powell as Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, another private detective who walks a fine line between the law and the criminal, also hard, impersonal and unemotional, also viewing the world and the people in it with a certain esoteric cynicism.

Bogart’s status is well known, a screen icon, and The Maltese Falcon ranks high in the litany of cinema greats. In a sense, much like Bogart, who would evolve from the typecast, malevolent gangster into the private detective who, instead of dying at the end of the last reel, now silently gloats over the criminal who does expire, Powell practically reinvented himself, becoming an entirely new man, escaping the musical for a totally different screen genre.

In the 1930s, Powell was well established—too established, he felt—as the romantic, bright-eyed singing lead in countless musicals, also at Bogart’s studio, Warner Bros.—in Gold Diggers of 1933, Footlight Parade, Flirtation Walk and, best of all, 42nd Street. When the studio refused to give him dramatic roles, Powell bought his way out of his contract, first lobbying for the killer of Barbara Stanwyck’s husband in Double Indemnity (1944). Fred MacMurray, making his own image shift away from nice guys, got the part of Walter Neff.

That same year Powell was awarded the lead in Murder, My Sweet as Philip Marlowe, the first actor to play the private eye on screen. The source was Farewell, My Lovely, Raymond Chandler’s second novel about Marlowe—the first was The Big Sleep—but the studio, now RKO, changed the title, fearing audiences might stay away thinking it was a musical.

Although Humphrey Bogart became the quintessential Philip Marlowe in his one and only appearance as the detective in The Big Sleep (1946), Powell holds his own among the best actors who subsequently played the role, including Bogart—among them Robert Montgomery in The Lady in the Lake (1947), James Garner in Marlowe (1969), even Philip Carey in a 1959-60 TV series and, of course, perhaps second only to Bogart, Robert Mitchum in remakes of both the correctly titled Farewell, My Lovely (1975) and The Big Sleep (1978).

Technically, the first Marlowe character appeared in the guise of the Falcon (George Sanders) in The Falcon Takes Over, an adaptation of Farewell, My Lovely. This was in 1942, two years before Powell’s “official” début of the character. Less well known, also in ’42, Lloyd Nolan had stood in for Marlowe, this time pseudonymed as Michael Shayne, in Time to Kill, from Chandler’s The High Window.

Technically, the first Marlowe character appeared in the guise of the Falcon (George Sanders) in The Falcon Takes Over, an adaptation of Farewell, My Lovely. This was in 1942, two years before Powell’s “official” début of the character. Less well known, also in ’42, Lloyd Nolan had stood in for Marlowe, this time pseudonymed as Michael Shayne, in Time to Kill, from Chandler’s The High Window.

Powell, now permanently forsaking singing, takes on dramatic roles and, though, like Bogart, he played Marlowe only once, he maintains his noir image. In 1945, he is reunited with his Murder, My Sweet director, Edward Dmytryk, in Cornered, still a film noir, but now about Nazis in Argentina. Two years later, Powell becomes the title character, a gambling house operator, in Johnny O’Clock, though less of a film than its two predecessors. With director André De Toth, Pitfall (1948) would be another near-great film noir, Powell now an insurance executive who tires of family life and falls under the wiles of a femme fatale (Lizabeth Scott).

One of the actor’s last films, another noir, is Cry Danger (1952), with Powell’s screen wife (Rhonda Fleming) as the woman of suspicion. Soon after, he becomes a director (The Enemy Below [1957], The Hunters [1958]), appears on television and then becomes a TV producer.

One of the actor’s last films, another noir, is Cry Danger (1952), with Powell’s screen wife (Rhonda Fleming) as the woman of suspicion. Soon after, he becomes a director (The Enemy Below [1957], The Hunters [1958]), appears on television and then becomes a TV producer.

The stylish noir quality of Murder, My Sweet has a revealing counterpart—perhaps as a source of inspiration?—in The Maltese Falcon. Dmytryk’s tight and dead-serious direction in Murder, My Sweet is akin to Huston’s, cold and often depressing, the love scenes tenuous and mildly tortured. Harry J. Wild’s cinematography in the Powell film has, too, the same economy of Arthur Edeson’s in Falcon, with only the occasional camera flourish.

Director Huston, who also scripted his movie, retains the bite of Dashiell Hammett’s dialogue. Even more famous, and with similar economic spice, is Chandler’s no-nonsense dialogue and, now added in Murder, My Sweet, the on-screen narration, which screenwriter John Paxton (On the Beach [1959}, Kotch [1971]) preserves so well and uses liberally. Some of the overtly sexual aspects of the novel never made it to the screen, owing to heavy Hollywood censorship at the time—not so much a concern in Mitchum’s 1975 remake.

Director Huston, who also scripted his movie, retains the bite of Dashiell Hammett’s dialogue. Even more famous, and with similar economic spice, is Chandler’s no-nonsense dialogue and, now added in Murder, My Sweet, the on-screen narration, which screenwriter John Paxton (On the Beach [1959}, Kotch [1971]) preserves so well and uses liberally. Some of the overtly sexual aspects of the novel never made it to the screen, owing to heavy Hollywood censorship at the time—not so much a concern in Mitchum’s 1975 remake.

If The Maltese Falcon has a score by Adolph Deutsch, Murder, My Sweet goes a composer better, with one by the notoriously neglected, underrated Roy Webb. While Deutsch might have scored more noir films during the ’40s, becoming something of a noir specialist, Webb, much the superior composer, made his own contributions to the genre—Journey into Fear (1943), The Fallen Sparrow (1943) and two of his best, The Spiral Staircase (1946) and Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946). Interwoven with these noirs of that decade are Webb’s more famous horror film scores, including The Curse of the Cat People (1942), The Body Snatcher (1945) and Bedlam (1946).

Webb’s music is intrinsically a part of Murder, My Sweet. It captures the nocturnal atmosphere, the unending night scenes, the fog, mist and general gloom, a palette of sometimes bitonal austerity, sometimes quasi-Impressionist clarity, sometimes an occasional contrasting lyrical calm (as in the love theme, again “tenuous,” never blatantly passionate), sometimes dense orchestration, sometimes airy and thin scoring.

Webb’s music is intrinsically a part of Murder, My Sweet. It captures the nocturnal atmosphere, the unending night scenes, the fog, mist and general gloom, a palette of sometimes bitonal austerity, sometimes quasi-Impressionist clarity, sometimes an occasional contrasting lyrical calm (as in the love theme, again “tenuous,” never blatantly passionate), sometimes dense orchestration, sometimes airy and thin scoring.

Some of Webb’s music was unfortunately cut from the final picture, in particular at least one segment that underpinned a Marlowe/Chandler narration. Sadly, Webb is silent more often than not—and any number of moments in the film would have benefited from more underscoring.

Imagine, though, being dropped into a film whose script and screen reflect all the bizarre moods, textures and undercurrents that the music patently suggests. The traditional RKO trademark fanfare, with its accompanying “Transmitter” logo, is abruptly followed by quiet trills in the orchestra—neither ominous nor anxious, merely neutral, bland.

Dim lighting, as always in the film, engulfs and sets the mood for the opening. Sitting at a table, two police detectives interrogate private detective Philip Marlowe, under suspicion for possibly two murders. From overhead, a camera descent on the table soon evolves into a full screen of white, then a view of a solitary ceiling light. Hovering shadows all about. Through the door, comes the police lieutenant, Randall (Donald Douglas), Marlowe’s nemesis, tormentor and verbal abuser. Sam Spade’s counterpart harassers in The Maltese Falcon are Barton MacLane and Ward Bond.

Dim lighting, as always in the film, engulfs and sets the mood for the opening. Sitting at a table, two police detectives interrogate private detective Philip Marlowe, under suspicion for possibly two murders. From overhead, a camera descent on the table soon evolves into a full screen of white, then a view of a solitary ceiling light. Hovering shadows all about. Through the door, comes the police lieutenant, Randall (Donald Douglas), Marlowe’s nemesis, tormentor and verbal abuser. Sam Spade’s counterpart harassers in The Maltese Falcon are Barton MacLane and Ward Bond.

The viewer won’t know why Marlowe has a bandage around his head and over his eyes until the end. He begins to tell his story. The film is a flashback. “Some of it you know . . . ” he says. The camera moves to a bare, uncovered window and, beyond, the city at night, neon signs, moving cars. The view is held for sometime, as Marlowe continues with a terse Chandler simile: “ . . . my mind felt like a plumber’s handkerchief . . . ”

Like so many noirs, this one begins with a search for a woman. A giant of a man, Moose Malloy (Mike Mazurki) hires Marlowe to find a long-lost girlfriend, Velma Valento. Throughout, the detective is led a merry chase, sidetracked more than once and always, always, from the darkness he encounters sinister, desperate characters with ulterior motives, most of them either wishing to use him or do him harm. The complexity of the plot—perhaps a little vague after a first viewing—puzzles even Marlowe, who admits it more than once during the proceedings.

At a nightclub where Velma once worked, the detective describes the outside: “The joint looked like trouble, but that didn’t bother me. Nothing bothered me. The two twenties [from Moose] felt nice and snug against my appendix.”

At the apartment of an old woman, Jessie Florian (Esther Howard, in a scene-stealing role), the one “with a face like a bucket of mud,” says she doesn’t know what became of Velma.

At the apartment of an old woman, Jessie Florian (Esther Howard, in a scene-stealing role), the one “with a face like a bucket of mud,” says she doesn’t know what became of Velma.

Then Lindsay Marriott (Douglas Walton) offers the detective $100 to accompany him as a bodyguard to an isolated canyon. Marriott is to meet someone and buy back a stolen necklace. Marlowe is knocked unconscious. “I caught the blackjack right behind my ear,” he describes to the audience. “A black pool opened up at my feet. I dived in. It had no bottom. I felt pretty good, like an amputated leg.”

As he’s regaining consciousness, a flashlight beam shines in his face. He hears a voice: “What happened? Are you all right?” He sees a girl’s face for a split second before she runs off. Back at the car, he finds a dead Marriott.

After being picked up by the police, Marlowe screams at Randall that he’s told him all he knows. He leans over the desk and shouts, “I’m tired of listening to your bum guesses. Either book me or let me go home to bed.” This should sound similar, for Spade also tells off the authorities in Falcon: “I don’t want any more informal talks. I’ve nothing to say to you . . . If you want to see me, pinch me or subpoena me, I’ll come down with my lawyer.”

After being picked up by the police, Marlowe screams at Randall that he’s told him all he knows. He leans over the desk and shouts, “I’m tired of listening to your bum guesses. Either book me or let me go home to bed.” This should sound similar, for Spade also tells off the authorities in Falcon: “I don’t want any more informal talks. I’ve nothing to say to you . . . If you want to see me, pinch me or subpoena me, I’ll come down with my lawyer.”

Marlowe is released and returns to his office where he finds a Miss Allison. She says she’s a reporter from The Post. That she asks him, “Did Marriott tell you who owned the jade he was buying back?,” shows she’s involved in the case. From the contents of her purse he abruptly dumps on his desk her bank book indicates she’s Ann Grayle (Anne Shirley in her last film, though she would live another fifty years). Ann says the necklace belonged to her father.

She drives Marlowe to her father’s house. Marlowe narrates: “It was a nice little front yard. Cozy. Okay for the average family, only you’d need a compass to go to the mailbox. The house was okay, too, but it wasn’t as big as Buckingham Palace. I had to wait until she sold me to the old folks. It was like waiting to buy a crypt in a mausoleum.”

Marlowe meets Ann’s elderly father, Leuwen Grayle (Miles Mander, good enough here and in other movies to have been given larger, better roles), and her mother-in-law, the young wife, Helen (Claire Trevor, drink in hand, yes, but not the drunk of Key Largo [1948]).

Marlowe meets Ann’s elderly father, Leuwen Grayle (Miles Mander, good enough here and in other movies to have been given larger, better roles), and her mother-in-law, the young wife, Helen (Claire Trevor, drink in hand, yes, but not the drunk of Key Largo [1948]).

Leuwen asks Marlowe to find the jade necklace for him, then excuses himself and he and his daughter leave. Marlowe and Helen sit on the sofa, sharing drinks as well as Chandler’s brittle, direct dialogue:

“Who could have known,” Marlowe asks, “you were going to wear the necklace this particular night?”

“My maid perhaps, but she’s had a hundred chances—besides, I trust her.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know,” she replies slowly. “I trust some people. I trust you.”

“Did you trust Marriott?”

“Not in some things—in others, yes. There are degrees.”

Marlowe puts down his drink.

“I thought,” she says, “detectives were heavy drinkers.”

“Some of them are. Some just encourage other people to drink.”

And on and on the plot, becoming more and more convoluted as Marlowe’s investigation becomes progressively more murky. When Ann turns up unexpectedly at a nightclub, he has one of his best lines: “I seem to remember you from my dreams—one of the better ones.”

He meets Jules Amthor (Otto Kruger, once again, the urbane, soft-spoken, acid-tongued villain of Hitchcock’s Saboteur). Moose, his cohort as it turns out, gives Marlowe a pistol whipping and sinister Dr. Sonderborg (Ralf Harolde) administers a hallucinogenic drug. Amthor wants to know where the necklace is, but Marlowe doesn’t know.

Familiar words as the detective says, “A black pool opened at my feet again. I dived in. . . . ” Webb’s sometimes dissonant and bitonal music comes into its own, reinforcing the swirling, spinning screen images as Marlowe literally dives into the nightmarish torture of the drug. On screen, his body falls into a whirlpool. He sees, if only in his frenzied imagination, distorted, screaming faces, extended clawing hands, rows of endless doors. And cobwebs. “The window was open, but the smoke didn’t move. It was a gray web woven by a thousand spiders. I wondered how they got them to work together.” A white-coated man approaches with a hypodermic, close-up of a needle, another whirlpool, more cobwebs, a revolving white light which turns out to be a chandelier.

Familiar words as the detective says, “A black pool opened at my feet again. I dived in. . . . ” Webb’s sometimes dissonant and bitonal music comes into its own, reinforcing the swirling, spinning screen images as Marlowe literally dives into the nightmarish torture of the drug. On screen, his body falls into a whirlpool. He sees, if only in his frenzied imagination, distorted, screaming faces, extended clawing hands, rows of endless doors. And cobwebs. “The window was open, but the smoke didn’t move. It was a gray web woven by a thousand spiders. I wondered how they got them to work together.” A white-coated man approaches with a hypodermic, close-up of a needle, another whirlpool, more cobwebs, a revolving white light which turns out to be a chandelier.

Marlowe gradually regains consciousness and escapes. Knowing Randall is watching his apartment, he goes to Ann’s. Still groggy from his ordeal, he stretches out on the sofa. She looks down at him, concerned, for the two have become close. “What happened? Are you all right?”

That voice! The girl in the canyon! Marlowe, in clearly a delayed revelation, realizes Ann Grayle and that girl are one and the same. For those who have paid special attention to the score, and haven’t already noticed the physical similarity, the clever Mr. Webb has linked the two with a single theme, first played in the canyon and later when the girl appears as Ann.

That voice! The girl in the canyon! Marlowe, in clearly a delayed revelation, realizes Ann Grayle and that girl are one and the same. For those who have paid special attention to the score, and haven’t already noticed the physical similarity, the clever Mr. Webb has linked the two with a single theme, first played in the canyon and later when the girl appears as Ann.

The climax and resolution of Murder, My Sweet comes at a favorite venue of film noirs, the beach house—Humoresque (1946), A Stolen Life (1946), Scream of Fear (1961) and Kiss Me Deadly (1955) where the house even explodes. The previous convolutions are here resolved—well, reasonably resolved, anyway. At this gathering of the “clans,” so to speak, the players enter one at a time or in pairs—Moose, Leuwen, Ann, Helen, who is revealed to be Moose’s lost girlfriend Velma, and, of course, Marlowe. And Amthor? Oh, he was found earlier with a broken neck.

There are arguments, revelations. Helen had killed Marriott in the canyon and was about to kill Marlowe when Ann appeared. Now a jealous Leuwen kills his faithless wife Helen, aka Velma, and also Moose, who tries to attack him. In Marlowe’s attempt to intervene, his eyes are seared by the blast from Leuwen’s gun.

Finally the present, the flashback concluded. Marlowe, his eyes still bandaged, is cleared and leaves the police station. Ann is there, but she motions for the detectives not to mention her presence. He is led to a taxi by one detective and Ann slips in beside him. He smells her perfume. They kiss, but not before Marlowe has removed his revolver from his inside coat pocket. After an embrace In an earlier scene, Helen had suggested he not wear his gun when kissing girls—the weapon could be felt.

Finally the present, the flashback concluded. Marlowe, his eyes still bandaged, is cleared and leaves the police station. Ann is there, but she motions for the detectives not to mention her presence. He is led to a taxi by one detective and Ann slips in beside him. He smells her perfume. They kiss, but not before Marlowe has removed his revolver from his inside coat pocket. After an embrace In an earlier scene, Helen had suggested he not wear his gun when kissing girls—the weapon could be felt.

Dick Powell was among the stars and crew whose cancers were suspected of coming from filming The Conqueror (1956), which Powell directed, downwind of the atomic bomb test grounds in southwestern Utah. The cancer deaths include John Wayne, Agnes Moorehead, Susan Hayward and Pedro Armendáriz, though Armendáriz shot himself rather than die a slow death. Both Powell and Wayne, however, were heavy smokers.