“Another woman once thought she owned me. Don’t drive me too far!” —Stephen Lowry to Lily Watkins

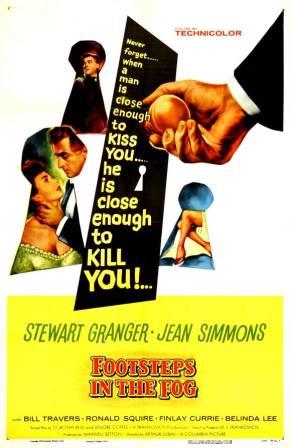

Stephen Lowry (Stewart Granger) is in deepest grief, face ashen, head bowed during the funeral of his wife. Around the grave in the interminable Victorian drizzle are his friends and acquaintances, solidly supporting the upstanding, much-admired Lowry—David MacDonald (Bill Travers), the girl of his infatuation, Elizabeth Travers (Belinda Lee), and her father Alfred (Ronald Squire).

Death has its fascinations, and any number of films open with a funeral—in Witness (1985) for the Amish husband of Kelly McGillis, in the comedy Mouse Hunt (1997) for the father of two sons who drop his coffin, in Chariots of Fire(1981) for Olympic runner Harold Abrahams and in The Big Chill (1983) for a body (Kevin Costner’s only appearance) being dressed for burial during the opening credits and whose mourners gather after the funeral to reminisce and review their past lives. A mortuary corpse is also seen behind the credits in Moonstruck (1987); here the central theme is death itself, with the one funeral deferred because an Italian mother refused to die.

In still other films the funeral occupies a more central position, sometimes influencing the whole mood of what follows, or at the least contributing a best-remembered scene. The macabre highlights of the comedy Death at a Funeral(2007) include a body falling out of its coffin and a second, later added and thought dead, leaping out alive. Friends gather to bury and remember Tom Doniphon in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) and discover who actually shot the outlaw Valance.

In Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994), though it’s only a small part of the movie, the funeral of the title is actually one of the few serious incidents in the film, certainly the most moving. While Charade (1963) may begin immediately with a body falling from a high-speed French train, the one funeral stands out. Only three people attend at first, the widow, her girlfriend and an apathetic police inspector; it’s the late “mourners” who make it special: the first suffers a sneezing fit, the second holds a hand mirror to the corpse’s mouth and the third pricks the departed with a straight pin.

Yes, death is so often . . . final !

In Footsteps in the Fog, after the carriage has stopped at Lowry’s home that is within the sound of Big Ben, Elizabeth and her father suggest he stay with them a while. “No,” he says, “I must face that empty house—and learn to be . . . alone.” His grief seems palatable to those in the carriage. He enters his plush London living room, fills a glass from the wine decanter and steps to a portrait of his late wife, a brooch watch on her bodice, a black cat on her lap. Lowry lifts the glass to the portrait and smiles. On his lips is smug satisfaction.

Moments later the attractive maid of the household, Lily Watkins (Jean Simmons), enters, compliments her master on how he alone attended his wife and asks what she can do. He suggests she remove the black cat, which had cowered at his approach.

“Well, it’s strange, sir,” she says, staring up at the portrait. “Whenever I look at her picture, I get this queer feeling—it’s almost as if she’s trying to tell me something.”

During the filming of Footsteps in the Fog, Granger and Simmons were midpoint in their ten-year marriage. He had proposed to her after seeing her in Black Narcissus (1947), and, besides Footsteps, they made three other films together: Caesar and Cleopatra (1945), Adam and Evelyne (1949) and Young Bess (1953).

He as the most popular male star of the British public in the ’40s and she as one of the ravishing beauties of both Britain and Hollywood, together they are a charismatic couple on screen, even through the variant moods and motives in Footsteps. As Lily, Simmons always conveys a sincere love for her master but with a woman’s cunning ambition. He presents whichever mood suits the occasion, whether anger, vengeance or a pretended love, and each is convincing—to Lily and to the audience.

Again in the presence of his wife’s portrait, when Stephen asks Lily why she is wearing his wife’s jewelry, she replies that she gave them to her. “Do you think for a moment,” he barks, “any one would believe that?”

“They all believe she died of gastroenteritis, don’t they?” she answers. “One’s as true as the other.” Stephen allows Lily to keep the jewelry.

Later, Lily relates to him her experiment with some unfortunate rats in the cellar, feeding them from the wife’s prescription bottle, which she had seen him hide in a potted plant. “I don’t think,” she says, “the police would believe they died of gastroenteritis.” She forces him to appoint her housekeeper over the nasty Mrs. Park (Marjorie Rhodes).

In Benjamin Frankel’s fittingly moody score, aside from the main title, which includes a lovely tune for Lily, a high-pitched ostinato—hardly a melody, only a fragment—is first introduced with a close-up of the medicine bottle in the cellar. This becomes a motif for the darker actions of the outwardly appealing Lowry and will sometimes be cleverly combined with other themes.

Frankel’s music takes center place in a scene when David takes Elizabeth for a ride in his horseless carriage. This jaunty, yet lyrical theme has never existed outside the film track, i.e. published separately; perhaps the composer felt it was too similar to his Carriage and Pair, which had already achieved public success. Frankel was part of the British tradition of quality light music, so popular in the early decades of the twentieth century and best exemplified by such composers as Ronald Binge, Armstrong Gibbs, Robert Farnon and, most famous, Albert Ketèlbey, for his “narrative music,” the exotic sound paintings of such miniatures as Bells Across the Meadow and In the Mystic Land of Egypt.

The horseless carriage scene begins as David, a barrister, warns his passenger that his motor car goes “jolly fast—twelve miles an hour.” His pursuit of Elizabeth suffers a setback when she confesses her attraction to Stephen Lowry. David warns that he is not the man for her, and further: “There’s something I can’t quite put my finger on. I don’t know what.”

Lily fails to take her master’s suggestion that she go to America or Canada for the greater opportunities. So when she goes out on a foggy evening, he grabs a heavy walking stick and follows her. Catching up to her violet coat and hood, he bludgeons the figure several times. Seen by two patrons emerging from a pub, he escapes back to the house.

The suspense of this scene is heightened, not only by Frankel’s music, which once again utilizes that demented ostinato, but by the cinematography of Englishman Christopher Challis. A specialist in color photography, he was an apprentice technician for a Technicolor lab in his early career, and his work is ideally represented in A Shot in the Dark(1964), The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1977) and The Deep (1977).

Lowry, back at home and still a bit ruffled from his “night out,” is surprised by a noise at the front door and the slow turning of the knob. Lily enters! She says if she hadn’t gone out she would have missed all the excitement—the wife of Constable Burke (Barry Keegan) had been killed. When straightening Stephen’s damp coat hanging on its rack, she finds blood. The two stare at one another, the otherwise silence filled with the clanging of the ambulance bell as the sound nears, then gradually fades. Lily remarks that she could have been in the ambulance, but that he should know she wouldn’t do anything to harm him.

Identified by the two men from the pub, Lowry is placed on trial, reluctantly defended by David. He is acquitted, however, when it’s revealed the two witnesses were drunk and when Lily testifies that Stephen was home during the murder, that the cane with his initials had been stolen several months earlier.

Stephen asks Lily if she isn’t afraid to be in the house alone with him, and she says she had written her sister a letter, to be opened if anything should happen to her.

In Footsteps in the Fog, there is that somewhat implausible personal relationship between master and servant and a number of plot improbabilities—certainly the one to come, Lowry’s last scheme against Lily. But with its craft and enthralling scenario, this Victorian drawing room drama/mystery holds together superbly. Although thoroughly British and made at Shepperton Studios in Surrey, the film has the slick production values of Hollywood at its height.

There is the credible acting by all involved, especially from the principals (Granger always seems his best in period pictures and Simmons is a delight in anything), but also stalwart contributions from each minor player. The Victorian interiors are plush and authentic, the settings atmospheric, with a hefty veneer of gloom—rain, fog, night scenes. Rich Technicolor. With a far better score than most accorded this genre, it is one of Frankel’s best, probably surpassed only byThe Seventh Veil (1945), his most famous and complex The Battle of the Bulge (1965) and preeminent, The Night of the Iguana(1964).

When Stephen and Elizabeth announce their engagement, Lily tells him she won’t allow it. He has no intention of marrying her he counters and, instead, proposes to Lily, kisses her and confesses his love. They’re going to America! But what about that letter? Taken in, Lily says she’ll write and tell her sister to burn it.

In truth, Lowry has a quite different plan. He frames her, placing in her room his wife’s jewelry and the bottle of poison. Over time, he takes small doses of the poison, requiring the convincing calls of a doctor (Frederick Leister). When Lowry grows worse—as, indeed, he is—Lily goes for the doctor. She assures him she’ll be back in five minutes. He takes a little more of the poison.

In the meantime, Lily’s sister’s husband Herbert (William Hartnell) reads the letter and approaches David MacDonald, mistaking him for Lowry—a bit far-fetched. His attempt to blackmail David puts him in jail. Inspector Peters (Finlay Currie) reads the letter and Lily is detained at the police station. Under watchful eyes, she is able to alter her handwriting from that in the letter, but on her way out she forgets and signs a release for false arrest in her natural handwriting.

Lily returns to the house and finds the doctor and Constable Burke. The evidence has been found in her room and Lowry, sprawled nearly unconscious in an armchair, accuses her of poisoning him and his wife. The doctor says it’s too late, he’s dying and the ambulance has been called.

“I timed it,” Lowry mumbles. “You said you’d be only five minutes!”

At that moment the sound of the clanging bell is heard again. “Remember that other ambulance,” Lily asks him, “and I said it could have been me?— I wish it had been.”