Indolent student, Bore War soldier, prisoner, fugitive and Member of Parliament—all from the life of a young Winston Churchill before the age of 27.

The critically successful Darkest Hour (2017) concentrates on Winston Churchill’s leadership during the Dunkirk retreat and evacuation in World War II. Young Winston, made almost half a century earlier, represents a somewhat broader time span in the great man’s life, from boyhood to his first parliamentary election in 1900.

The release of the British film in 1972 was partly the result of a renewed interest in Churchill’s life, inspired by his passing in January of 1965. Some people saw his death as the last vestige of the glorious British Empire, though, in every practical sense, the Empire had ended with World War I. Then called “the Great War,” who could know there would be one even more catastrophic! To historians and intuitive citizens at the time, the Empire’s decline had already begun by the turn of the twentieth century.

With England’s antiquated film industry in the 1930s, it was Hollywood which championed that country’s past—its mastery of the seas, its imperialistic success (and arrogance), most evident in its abuse of India, and its amassing an empire upon which the sun never set.

Hollywood made Mutiny on the Bounty in 1935 and its remake in 1962. It filmed The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936), climaxed by the infamous British blunder in the Crimean War. The studios seemed fascinated by the British exploits in India: Clive of India (1935), The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (1935) andGunga Din (1936).

In 1940, it was Hollywood which contrived a morale-building script for the Errol Flynn swashbuckler The Sea Hawk, relating its story of King Philip II’s sixteenth-century Armada to England’s current attacks by Hitler’s Luftwaffe. In much the same way, Mrs. Miniver (1942) extolled the bravery of the island’s citizens against Nazi fighters and their courage and national pride during the evacuation from Dunkirk.

From the ’60s to ’80s, before epics became largely too expensive, the British themselves began glorifying their past on film, either on their own or, usually, with American financial backing. They made Lawrence of Arabia in 1962 and remade The Charge of the Light Brigade in 1968. Khartoum (1966), about another Empire misadventure, now in the Sudan, stars an American, Charlton Heston, as Englishman General Charles George Gordon, the central character, but it is a Brit, Laurence Olivier, as Gordon’s nemesis, the Mahdi, the supposed redeemer of Islam, who, in history, does him in and, on screen, out-acts him.

From the ’60s to ’80s, before epics became largely too expensive, the British themselves began glorifying their past on film, either on their own or, usually, with American financial backing. They made Lawrence of Arabia in 1962 and remade The Charge of the Light Brigade in 1968. Khartoum (1966), about another Empire misadventure, now in the Sudan, stars an American, Charlton Heston, as Englishman General Charles George Gordon, the central character, but it is a Brit, Laurence Olivier, as Gordon’s nemesis, the Mahdi, the supposed redeemer of Islam, who, in history, does him in and, on screen, out-acts him.

And there is always the British indulgence in the Edwardian period and its attempted continuance, at least in thought and spirit. Film scholar Leslie Halliwell refers to the E. M. Forster adaptations of A Passage to India (1984), A Room with a View (1985) and Howards End (1991) as “filmed in a mood of nostalgic Edwardiana.” This can also be applied to the milieu of many other British films that relive the past—Chariots of Fire (1981) and The Remains of the Day (1993).

More recently, Edwardian aristocratic life is microscopically detailed in the British TV series Downton Abbey (2011-2016 on PBS). The six-year-long screen diversion begins in 1912 with the sinking of the Titanic and ends in 1926; in between comes World War I, the rude intrusion of the modern age, British estate taxes and the dissolution of most of the landed gentry.

More recently, Edwardian aristocratic life is microscopically detailed in the British TV series Downton Abbey (2011-2016 on PBS). The six-year-long screen diversion begins in 1912 with the sinking of the Titanic and ends in 1926; in between comes World War I, the rude intrusion of the modern age, British estate taxes and the dissolution of most of the landed gentry.

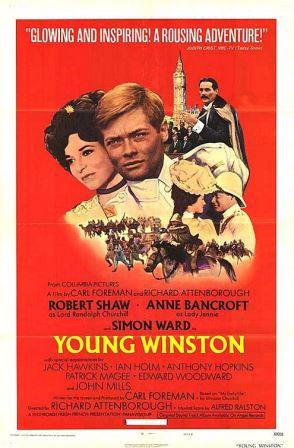

Young Winston, which takes places in both the Victorian and Edwardian periods, has a fine ensemble cast—all British save American Anne Bancroft as Churchill’s beautiful mother, Jennie. It can only be assumed that John Gielgud was otherwise occupied, reason he didn’t join the impressive cast of Robert Shaw, Jack Hawkins and John Mills and Patrick Magee as two generals.

There is also Edward Woodward, Robert Hardy (who would play Churchill in five separate British TV series), Laurence Naismith, Colin Blakely (a reliable Dr. Watson to Robert Stephens’ detective in The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, 1970), Jane Seymour, Anthony Hopkins (here as Lloyd George), Nigel Hawthorne and Ian Holm (the athletic trainer in Chariots of Fire).

Relative newcomer at the time, Simon Ward is the mature, mid-twenties Churchill. Two other child actors play Churchill at seven and thirteen, and Ward dubbed the voice of the thirteen-year-old (Michael Audreson). Ward was deprived, for whatever the reasons, of any great movie success, and the small part in the poorly drawn Hitler: The Last Ten Days (1973) somehow symbolizes his career.

Relative newcomer at the time, Simon Ward is the mature, mid-twenties Churchill. Two other child actors play Churchill at seven and thirteen, and Ward dubbed the voice of the thirteen-year-old (Michael Audreson). Ward was deprived, for whatever the reasons, of any great movie success, and the small part in the poorly drawn Hitler: The Last Ten Days (1973) somehow symbolizes his career.

The story line of the film moves from 1881 to 1901, the year the namesake of that age, Edward VII, came to the throne. When the movie opens, for it is a flashback with a reflective Winston narrating, it is already 1897 and the twenty-four-year old is in India. As a journalist for London’s Daily Telegraph, he craves battlefield glory and a writer’s fame.

While he is annoying the commander, Lord Kitchener (Mills), who cries out, “Who’s that bloody fool on the gray?,” Winston recalls his life in a boarding school. Lonely, he writes his parents fallacious letters that everything is jolly fine. He repeatedly asks them to come and visit, but they rarely do. (At about the same time, an unhappy fifteen-year-old Franklin Roosevelt is also writing home, he from Groton School, about the “wonderful” time he, too, is having. In the 1940s, the two men’s lives would cross in a way that, some say, “saved the world.”)

While he is annoying the commander, Lord Kitchener (Mills), who cries out, “Who’s that bloody fool on the gray?,” Winston recalls his life in a boarding school. Lonely, he writes his parents fallacious letters that everything is jolly fine. He repeatedly asks them to come and visit, but they rarely do. (At about the same time, an unhappy fifteen-year-old Franklin Roosevelt is also writing home, he from Groton School, about the “wonderful” time he, too, is having. In the 1940s, the two men’s lives would cross in a way that, some say, “saved the world.”)

When Winston is physically abused in the boarding school, it is “Wommy,” as the child calls his beloved nurse, Mrs. Everest (Pat Heywood), who insists to his mother, Lady Randolph, that he must be removed. Later, at the British military academy of Sandhurst, he proves a poor student.

His father, Lord Randolph (Shaw), while highly disappointed in his son’s performance yet professing love for him, begins acting erratically and becomes unreasonably angry toward him. Soon after he resigns as Chancellor of the Exchequer over an issue in Parliament, two doctors (Clive Morton and Robert Flemyng)—in a frank discussion, even for 1972—inform Lady Randolph that her husband is suffering from syphilis.

After Lord Randolph dies, money lost in the American stock market leaves the family destitute. Thanks to Jennie’s connections, Winston receives a commission in the British Army, which enables him to continue as a reporter, now for The Daily Mail.

After Lord Randolph dies, money lost in the American stock market leaves the family destitute. Thanks to Jennie’s connections, Winston receives a commission in the British Army, which enables him to continue as a reporter, now for The Daily Mail.

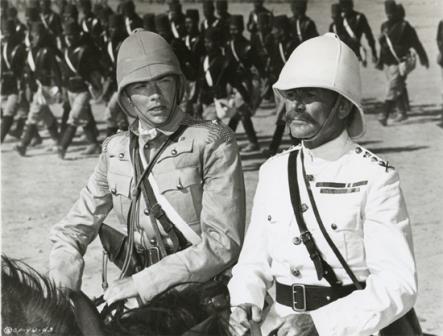

His later transfer to the Sudan satisfies, at least for the moment, his appetite for action and bravery. When he warns Kitchener of advancing Muslim warriors, the Dervishes, he is regarded as more than a naive nuisance.

Back in England, thanks to pressure from Jennie, Winston runs for Parliament, but lack of experience and a stuttering speech impediment lead to defeat. At the start of the Boer War in 1899, Winston receives another military commission, now in South Africa. He is captured by the Boers and imprisoned, but miraculously escapes, hides on a train and eventually returns to England.

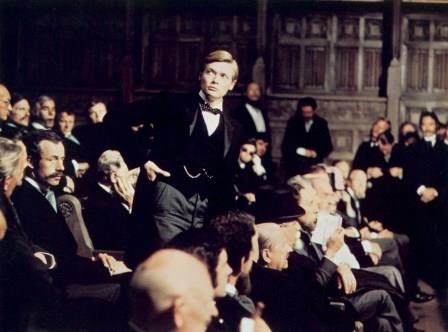

He is hailed as a hero and wins a seat in Parliament where he gives a resounding speech in the House of Commons. Soon afterward, Jennie, in discussing his future, happens—not so coincidentally, perhaps?—to introduce him to a young lady, soon-to-be wife Clementine Hozier.

Young Winston’s musical score, by Alfred Ralston, basically an arranger, is saved by the use of music of Sir Edward Elgar, the Edwardian composer par excellence. The Caractacus and Imperial marches enliven some battle scenes, the Pomp and Circumstance March No. 4 is fortunately substituted for the famous No. 1, everyone’s graduation march, and “Nimrod” from the Enigma Variations serves well whatever a composer needs a bit of ready-made British solemnity.

Young Winston’s musical score, by Alfred Ralston, basically an arranger, is saved by the use of music of Sir Edward Elgar, the Edwardian composer par excellence. The Caractacus and Imperial marches enliven some battle scenes, the Pomp and Circumstance March No. 4 is fortunately substituted for the famous No. 1, everyone’s graduation march, and “Nimrod” from the Enigma Variations serves well whatever a composer needs a bit of ready-made British solemnity.

As a final footnote, actors who have played Winston Churchill over the years are copious, and a complete list is far beyond the limits here. One of the earliest names, Dudley Field Malone, is attached to Hollywood’s now notorious, pro-Russian propaganda, Mission to Moscow (1943).

Later come Patrick Wymark in Operation Crossbow (1965), Leigh Dilley in The Eagle Has Landed (1976), Howard Lang in the TV series Winds of War (1983), Albert Finney in the TV movie The Gathering Storm(2002)—title of the first of Churchill’s six-volume The Second World War, Timothy Spall in The King’s Speech(2010) and, most recently, Gary Oldman in Darkest Hour.

While these titles represent the Winston Churchill of World War II, Young Winston provides glimpses into the earlier life of this soldier, writer, historian and statesman. Already a full, exciting life at twenty-seven, Churchill’s next sixty-three years would make him world famous, with his unheeded warnings of the menace of Hitler and his defiant leadership of the British people during World War II.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LxoOiTgFHPI[/embedyt]