Responding to a movie you’re watching, maybe you’ve asked yourself, “Hey, what’s going on here? That isn’t right. Where did that come from?” A mistake? Very possible. It happens more often than you’d think, and sometimes it requires several viewings of a film to realize that what you’ve seen is there—a mistake.

Out-and-out, on-screen boo-boos come in all forms. They have passed unnoticed by the director, the editor or the studio executive who watches a just-finished film and approves its release. On rare occasions, an error is seen and ultimately left in because of the expense of re-shooting.

A mistake can be the shadow of a microphone boom, the reflection of the crew in a mirror or storefront plate glass, even a worker accidentally caught within camera range.

Easy mistakes to make are the anachronistic ones, understandable considering the speed and sometimes haphazard nature of much film-making. This could be a clothes style not of the time period, an item not invented until centuries later, an edifice yet to be built, distant mountains in a flat country or a shown custom—fruit, animal, could be anything—not native to the country of the movie’s setting. And on and on—the possibilities for inaccuracies are endless.

A mistake that was corrected prior to release—at much expense—occurred in the last half of 1958 during the filming of North by Northwest (1959). In the famous crop-dusting scene, Cary Grant escapes from the attacking bi-plane into a cornfield, whereupon the plane promptly sweeps over with a cloud of insecticidal dust. As the film’s story and screenwriter, Ernest Lehman, relates in his commentary on the DVD, the first time the actor emerges from the cornfield and attempts to flag down a passing motorist, his suit is spotless—no residual dust. Peggy Robertson, the script supervisor and responsible for continuity, was greatly distressed and Alfred Hitchcock had to re-shoot Grant’s emergence from the cornfield, now with the dust.

A mistake that was corrected prior to release—at much expense—occurred in the last half of 1958 during the filming of North by Northwest (1959). In the famous crop-dusting scene, Cary Grant escapes from the attacking bi-plane into a cornfield, whereupon the plane promptly sweeps over with a cloud of insecticidal dust. As the film’s story and screenwriter, Ernest Lehman, relates in his commentary on the DVD, the first time the actor emerges from the cornfield and attempts to flag down a passing motorist, his suit is spotless—no residual dust. Peggy Robertson, the script supervisor and responsible for continuity, was greatly distressed and Alfred Hitchcock had to re-shoot Grant’s emergence from the cornfield, now with the dust.

So much for a continuity error that was caught. What about just two that were not? In Brief Encounter (1945), Celia Johnson runs through a downpour but remains dry. And in Casablanca (1942), after reading Lisa’s (Ingrid Bergman) “dear John” letter in the rain, Humphrey Bogart steps aboard a train—his raincoat completely dry.

Camera and microphone shadows are perhaps the most common of all slip-ups. In that heartwarming Christmas delight, Miracle on 34th Street (1944), Edmund Gwenn and John Payne walk across a square accompanied by a camera shadow. And over a pile of naval officers’ hats in the beginning of In Harm’s Way (1965), a mike boom shadow moves uninvited.

Then when shadows are needed, in The Birds (1963), the special effects crows which attack the children as they flee the school cast no shadows, nor do the carriages in Gone with the Wind (1939) as they pass through the avenue of oaks to the Wilkes barbecue. Jack Cosgrove, the visual effects artist, didn’t have time to add the shadows before the film was dispatched for its Atlanta premiere.

What you wear can trip you up. In The Viking Queen (1967), one actor sports a wrist watch, in One Million Years BC (1966), all the women wear false eyelashes, in Camelot (1967), Richard Harris has a Band-Aid on his neck in one scene and in Fire Maidens from Outer Space (1955), Sydney Tafler, wearing a T-shirt, glances at his wrist watch—on an arm covered by a long sleeve shirt.

And, in the other direction, what the well-undressed man shouldn’t be wearing tripped up Claude Rains in The Invisible Man (1933). In his invisible and stripped state, he should have left footprints in the snow, but he forgot to remove something, leaving shoeprints! He was caught anyway, unable to become what he needed to become—weightless.

And, in the other direction, what the well-undressed man shouldn’t be wearing tripped up Claude Rains in The Invisible Man (1933). In his invisible and stripped state, he should have left footprints in the snow, but he forgot to remove something, leaving shoeprints! He was caught anyway, unable to become what he needed to become—weightless.

Speaking of horror films, during the opening train ride in Son of Frankenstein (1939), Basil Rathbone mentions the desolate countryside passing outside the window, and the same tree appears three times.

It seems impossible to make a war film, especially ones about World War II because so many were made, without an enormous number of mistakes. In the distance a big gun fires or a bomb drops and the flash is always seen simultaneously with the noise of the explosion. This is even replicated in combat newsreels where sound is often added later. As everyone should know, light travels infinitely faster than sound. No matter what the war film—one of the greats (The Longest Day, 1962, Patton, 1970, or otherwise (Night of the Generals, 1967)—the errors abound: flags flying upside-down, wrong military dress ensigns, unconvincing ship models, weapons not yet developed, map inaccuracies, ad infinitum.

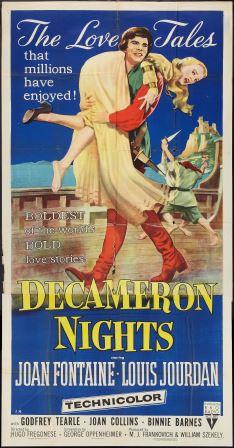

Automobiles, TV antennas, telephone poles—anything modern—in period-set films are never intentional, but, of course, they do sometimes appear. In Decameron Nights (1953), Louis Jourdan stands on the deck of a fourteenth-century pirate ship, and on a hill in the distance lumbers a large white truck. A modern car lies abandoned beside the road in Hello, Dolly! (1969), set in the early 1900s. During a battle sequence In The Alamo (1960)—this supposedly 1836—production trailers are clearly seen.

Automobiles, TV antennas, telephone poles—anything modern—in period-set films are never intentional, but, of course, they do sometimes appear. In Decameron Nights (1953), Louis Jourdan stands on the deck of a fourteenth-century pirate ship, and on a hill in the distance lumbers a large white truck. A modern car lies abandoned beside the road in Hello, Dolly! (1969), set in the early 1900s. During a battle sequence In The Alamo (1960)—this supposedly 1836—production trailers are clearly seen.

Which brings up Westerns. Like war films, they are especially prone to mistakes, from airplane vapor trails in the sky to rubber tire tracks on the ground, as in Stagecoach (1939) when the Indians chase the coach across the salt flats. It’s correctly taken for granted when Indians play Indians, assuming they aren’t played by white men, they are rarely of the tribe depicted. Not because it’s a Western—this error could occur in any genre film—in The Scalphunters (1968), Ossie Davis mentions the planet Pluto, which wasn’t discovered until 1930.

Simple geography can also be a problem. In Dracula (1932), Bela Lugosi refers to Whitby as “so close to London,” when, in fact, it’s over 240 miles away. Also inLondon, in 23 Paces to Baker Street (1956), Van Johnson’s apartment in Portman Square offers a river view of the Savoy Hotel, two miles away. In Knock on Wood(1954), Danny Kaye walks down London’s Oxford Street and turns the corner onto Ludgate Hill, three miles away.

Seemingly harmless, inert building can also cause trouble. In 1804, the time period of Emma Hamilton (1969), Big Ben is heard to strike—fifty years before its tower, recently renamed the Elizabeth Tower, was built. In The Lodger (1944), Tower Bridge is shown ten years before it was built. Errors befall New York, too. InRound Midnight (1998), set in the 1950s, a scene shows the World Trade Center towers, opened in 1973.

During an exterior scene In The Robe (1953), in which Victor Mature is being manhandled by some Roman centurions, sitting on the railing of a distant balcony, along with what appears to be other replicas of great Renaissance statuary, is a copy of Michelangelo’s famous David, carved fourteen centuries later.

During an exterior scene In The Robe (1953), in which Victor Mature is being manhandled by some Roman centurions, sitting on the railing of a distant balcony, along with what appears to be other replicas of great Renaissance statuary, is a copy of Michelangelo’s famous David, carved fourteen centuries later.

Objects which disappear and reappear or change position easily cause chuckles, and usually result from the numerous set-ups during filming. In Tea and Sympathy (1956), starring Deborah Kerr and John Kerr, a pair of china dogs on a mantel are back-to-back in one cut, face-to-face in another. When Yul Brynner sings his soliloquy “A Puzzlement” in The King and I (1956), sometimes he’s wearing an earring in his left ear—he wears only the one—sometimes not.

In Desk Set (1957), Katharine Hepburn leaves her office carrying a bouquet of white flowers and when she reaches the outside, they have become pink. A policeman rushes up a flight of stairs wearing a helmet in Knock on Wood and into the room wearing a peaked cap. During the banquet in the forest in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), Errol Flynn takes a bite out of a whole leg of mutton and in the next shot only the bone remains.

And beware of what’s seen in print in the movies. In Triple Cross (1966), a World War II newspaper headline laments the increasing price of the Concorde. In another newspaper, this in Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942), a photograph accompanying a story about the torpedoing of the “Lusitania” shows a vessel with two funnels; the liner had four. In Bette Davis’ The Corn is Green (1945), the supposedly illiterate villagers gather around to read a poster, much as citizens, also presumed to be illiterate, do in The Mark of Zorro (1940).

Songs and when they were written can be troublesome. In the 1904 setting of The Eddie Cantor Story (1953), Eddie sings “Meet Me in Dreamland,” written in 1909. “Baby Face,” sung in 1922 in Thoroughly Modern Millie (1967), wasn’t written until 1926. For that matter, a number of the songs heard in the 1883 period ofLife with Father (1947) were written later, most conspicuously Will F. Denny’s “Sweet Marie,” written ten years later.

When it’s all said and done, what does it matter, these boo-boos? As Alfred Hitchcock said, “It’s only a movie,” although said in the context of an actress’s concern for how to play a part.

“The first take, even with fluffs, is always the best,” remarked the great John Ford, who was less concerned about screen mistakes than most directors. He appreciated the spontaneity in shooting a scene, ever-ready for the unexpected. If a dog wandered into a shot, as one did in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), or if Ward Bond’s revolver went off prematurely, as happened in The Searchers (1956), that was fine—they were left in.

During the filming of a favorite Ford set-up, a column of approaching cavalry, this time in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, a lightning storm suddenly erupted. Cinematographer Winton C. Hoch called a halt, but Ford said to continue shooting. It became a celebrated Ford scene and contributed to Hoch winning an Oscar.