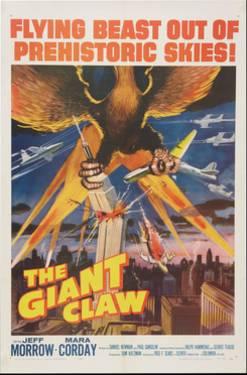

“Something, he didn’t know what, but something as big as a battleship has just flown over and past him.” — Narrator

They all should’ve known better. But how were the actors to know? None of them had seen the film’s special effects until after the theatrical release. No careers, however, seemed to have suffered.

Jeff Morrow, the only star approaching first tier status among the otherwise supporting players, saw the finished film for the first time at a hometown theater. Horrified by the first sight of the ridiculous birdlike creature belonging to the claw—claws, actually—Morrow sneaked out of the theater, hoping, and perhaps praying, that no one recognized him.

Not a standard-bearer for ’50s horror films, Columbia studios, which did produce the outstanding Curse of the Demon in 1957, should have been ashamed of The Giant Claw. Too cheap apparently to utilize the available talents of Ray Harryhausen’s stop animation, which they had employed two years earlier for It Came from Beneath the Sea, producer Sam Katzman employed a Mexican company, with hilariously unterrorizing results.

For almost the first half hour of The Giant Claw, the story-line fairly well maintains the suspense and craftily suppresses any premature revelations of the signature monster. All the actors are thoroughly “with it,” giving sincere performances, especially the reliable Morris Ankrum as an Army general anxious for Morrow’s help in saving the world from this deadly menace.

Mara Corday as Morrow’s almost girlfriend—the script stops short of moving their relationship beyond the I-think-I-kinda-like-you stage—is quite convincing, as well as attractive. She’s the standard girl Friday of the horror films who shares Morrow’s encounters with danger.

Mara Corday as Morrow’s almost girlfriend—the script stops short of moving their relationship beyond the I-think-I-kinda-like-you stage—is quite convincing, as well as attractive. She’s the standard girl Friday of the horror films who shares Morrow’s encounters with danger.

Mitch MacAfee (Morrow), a civil aeronautics engineer at a North Pole Air Force base, is testing the accuracy of his new radar system. In flight, he’s aware of something large flying over his aircraft the “size of a battleship,” an expression which becomes a tedious wordplay-cliché among others, and quickly outstays its welcome. Strange, the presence of any aircraft or object other than his own plane doesn’t register on the radar.

When one of the three U.S. Air Force planes dispatched to the area becomes lost, the base commander (Clark Howat) claims it’s just a misreading by Mitch’s new radar. Then a commercial airline pilot reports seeing a UFO just before his plane disappears.

On a flight to New York, Mitch and Sally Caldwell’s (Corday) plane encounters an assumed UFO—still nothing more than a fast-moving blur. The pilot (Frank Griffin) is killed in the attack and the craft crashes and explodes. Mitch and Sally survive unscathed and are befriended by a nearby farmer, Pierre (Louis Merrill) who takes them in.

That night, hearing a noise, Pierre goes outside to check on his animals but soon screams. Mitch and Sally find a terrified man, who says he saw a monstrous bird, “with wings bigger than I can tell.” Mitch pacifies him, suggesting it was probably just an eagle. No, Pierre says it was la Carcagne, a mythical bird, a legend of his people and seeing it means death (the actual la Carcagne is quite different in appearance).

That night, hearing a noise, Pierre goes outside to check on his animals but soon screams. Mitch and Sally find a terrified man, who says he saw a monstrous bird, “with wings bigger than I can tell.” Mitch pacifies him, suggesting it was probably just an eagle. No, Pierre says it was la Carcagne, a mythical bird, a legend of his people and seeing it means death (the actual la Carcagne is quite different in appearance).

On another flight to New York, after Mitch and Sally have exchanged some romantic banter, Mitch recognizes a pattern in the creature’s sightings that indicate a supersonic speed.

For twenty-seven minutes the audience has been spared. No longer. The next day the plot of a plane transporting a Civil Aeronautics team to investigate the earlier plane crash reports a UFO, now revealed for the first time as a creature-bird. Clearly a puppet. It has a chicken body, two claws and an ostrich neck, head and beak, as frightening as a badly drawn cartoon. Its unaerodynamic shape makes impossible its supposed supersonic speed. The narrator (Fred F. Sears), whose voice had prefaced the film, recycles that cliché, now “a bird as big as a battleship.”

The aeronautics team, obviously pessimistically expecting the worst, are already wearing parachutes and quickly exit the plane, which the bird now grabs in its beak. It devours one of the parachutists as he floats toward earth, all the while emitting an irritating one-note squawk, about as frightening as a barnyard rooster’s crow.

The aeronautics team, obviously pessimistically expecting the worst, are already wearing parachutes and quickly exit the plane, which the bird now grabs in its beak. It devours one of the parachutists as he floats toward earth, all the while emitting an irritating one-note squawk, about as frightening as a barnyard rooster’s crow.

The bird soon wreaks havoc, destroying the Empire State and U.N. buildings, populations flee cities and armies gather in defense, the usual plot procedure in monster films of this ilk.

Mitch, with the help of Sally and a fellow scientist (Edgar Barrier), works on a gun using isotopes to neutralize the bird’s antimatter shield, which has made it indestructible. First, firing the isotopes from the tail of a B-25 successfully collapses the creature’s protection, then with the plane’s rockets the bird is brought down, dead into the sea.

If the stars had seen the bird-creature during filming, perhaps their performances would have been less convincing. Certainly the film would have been more expensive, with all those retakes to eliminate the irrepressible, uproarious laughter. Some critics have defended The Giant Clawbased on the competent performances, that without the poor special effects, the film isn’t all that bad.

No! The bird puppet negates the film as a whole. It’s not supposed to be a comedy, after all.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9zBllkB04TI[/embedyt]