“[Hal] Wallis’ notion that [a certain action scene] could be depicted solely through the use of stock footage was emblematic of the difference between the executive producer, who viewed movies as the product of an assembly line, and the director, who considered every film a personal artistic statement.” — Chapter 22

Directors come and go, much like the films they make and the stars who appear in them. Some directors, well known and respected, say, in the 1920s, remain in the remembered forefront of film history, sometimes for a single film—Sergei Eisenstein because of Battleship Potemkin(1925), or Erich von Stroheim and Greed (1925), or F. W. Murnau and Nosferatu (1922).

In other cases, films themselves, more often the stars, survive while the directors are forgotten. In the milestone The Mark of Zorro (1920) which launched the swashbuckling career of Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., who recalls the director’s name? Fred Niblo, wasn’t it?

Perhaps it’s unfair to look back so far. The ’30s, then. The Thin Man (1934) stars William Powell and Myrna Loy—well known stars—but the director, who helmed this and three of the six subsequent films in the series, is far less well known to the average movie-goer, though not, perhaps, to the true film buff. Clearly better remembered than Niblo, W. S. Van Dyke was known as “One-Take Woody.”

Although some of the great directors were more diverse in their subject matter than others—William Wyler, Henry King and John Huston, for example—a larger number have entered the pantheon of greats because of a specific genre—Frank Capra for social comedy, Fritz Lang for film noir, Henry Hathaway, Sergio Leone and John Ford for Westerns, Roger Corman for horror and, of course, the most one-genre-centered director of all, Alfred Hitchcock for suspense.

Still, another director, one of the most diverse of all, is also, unfortunately, one of the most underestimated and overlooked. He was able—not a supposition but a fact—to do any and everything equally well, from Westerns (Dodge City, 1939) to swashbucklers (The Adventures of Robin Hood, 1938, and The Sea Hawk, 1940), fromfilm noir (Casablanca, 1942) to comedies (Life with Father, 1947), from social reform (20,000 Years in Sing Sing, 1932) to, yes, even horror (The Walking Dead, 1936), from detective capers (The Kennel Murder Case, 1933) to musicals (Yankee Doodle Dandy, 1940, and White Christmas,1954).

He received best-director Oscar nominations for Captain Blood (1935) (placing second as a write-in), Four Daughters and Angels with Dirty Faces (both 1938) and Yankee Doodle Dandy. He took home the statuette for Casablanca, regarded by many as, if not the greatest, then the most popular, most-loved film ever made. He directed over 170 movies during his career, which included those between 1917 and 1926 in his native Hungary and in Germany.

He received best-director Oscar nominations for Captain Blood (1935) (placing second as a write-in), Four Daughters and Angels with Dirty Faces (both 1938) and Yankee Doodle Dandy. He took home the statuette for Casablanca, regarded by many as, if not the greatest, then the most popular, most-loved film ever made. He directed over 170 movies during his career, which included those between 1917 and 1926 in his native Hungary and in Germany.

The man who became famous for mangling the English language—“Bring on the empty horses,” which David Niven used as the title of a Hollywood memoir—was born Manó Kaminer in 1886 in Budapest, then a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Screen-credited in Europe either as Kertész Mihály or as Mihály Kertész, in his first American film (The Third Degree, 1926) and thereafter, he became Michael Curtiz.

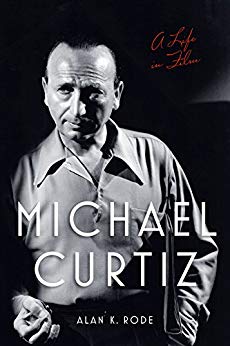

Written in 2017, Alan K. Rode’s Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film provides the most complete biography of the film director to date. Thorough and detailed, with numerous revelations of heretofore unknown facts and anecdotes, Rode’s style remains easily readable, approaching can’t-put-down status. While the bibliography and index are exactingly complete, the avid film buff would have liked a few more stills.

Curtiz was known to have fathered several children out of wedlock, divorced a first wife, Lucy Doraine, and a second, Lili Damita (Errol Flynn’s first wife), after less than a year of marriage, before marrying Bess Meredyth, a New Yorker. Despite the more or less typical Hollywood private interests—philandering and partying with Hollywood’s elite—most of A Life in Film is devoted to the director’s art of movie-making, as it should be.

Curtiz was known to have fathered several children out of wedlock, divorced a first wife, Lucy Doraine, and a second, Lili Damita (Errol Flynn’s first wife), after less than a year of marriage, before marrying Bess Meredyth, a New Yorker. Despite the more or less typical Hollywood private interests—philandering and partying with Hollywood’s elite—most of A Life in Film is devoted to the director’s art of movie-making, as it should be.

Perhaps most essential in a biography, the life revealed is straightforward and unadorned by any softening of the subject’s character, for Curtiz—how does the cliché go?—worked in the tradition of “the good old days.” Then, like those autocratic German conductors of yore, directors, Curtiz included, were often tyrants—not that there aren’t still some of that breed making movies today.

A list of three such tyrants would have to include Otto Preminger, John Ford and Cecil B. DeMille. Preminger was nasty, Ford mean and DeMille shared Curtiz’ disregard for the safety of the actors, feeling that they were expected to risk their lives for the sake of a film.

Raymond Massey and Ronald Reagan can attest to an incident which occurred during filming of Santa Fe Trail (1940). A minor supporting actor playing a minister stepped back out of the way as the director was framing a camera shot and promptly fell down an empty water tank. According to Massey, “Before he hit bottom, Mike muttered, ‘Get another parson!’ ”

Fay Wray recalled one example of Curtiz’ cruelty. “Looking through the finder one day at a group of extras, he called out to one, ‘Move to your right . . . more . . . more . . . more . . . Now you’re out of the scene. Go home!’So wicked, it was almost funny.”

Hitchcock might have said, “It’s only a movie,” but to Michael Curtiz that image up on the screen was more, much more. He was the ideal artist, who, as Rode wrote, “ . . . considered every film a personal artistic statement.” It was not uncommon for Curtiz to drive cast and crew long beyond the normal work day—ten, twelve, even eighteen hours straight. And what was this big deal about breaking for lunch? “Why should they eat? I don’t eat! Why should we be wasting this time?”

Hitchcock might have said, “It’s only a movie,” but to Michael Curtiz that image up on the screen was more, much more. He was the ideal artist, who, as Rode wrote, “ . . . considered every film a personal artistic statement.” It was not uncommon for Curtiz to drive cast and crew long beyond the normal work day—ten, twelve, even eighteen hours straight. And what was this big deal about breaking for lunch? “Why should they eat? I don’t eat! Why should we be wasting this time?”

Starring in Cabin in the Cotton (1932), the first of her seven films with Curtiz, Bette Davis said he was more concerned about camera and lighting set-ups than about the actors. “Mike must have hated his wife,” remarked actor Lyle Talbot, star of the director’s The Big House (1930), “because he never wanted to go home.” Truth was, Michael Curtiz loved to make movies.

Curtiz was a workhorse and expected everyone else to be one as well. On the one hand, he made an extra effort to please penny-pinching studio head Jack Warner, especially in his first years in America when his immigration status was tenuous (he became a citizen in 1936).

On the other hand, he added any number of scenes and extemporized with elaborate and expensive, time-delaying set-ups. He took nearly eight hours to shoot a close-up of Boris Karloff’s face in The Walking Dead. For The Sea Hawk, he added thirty-four unscripted scenes! Unlike Ford and Hitchcock who cut in the camera, Curtiz shot a scene from several angles, resulting inover-coverage.

On the other hand, he added any number of scenes and extemporized with elaborate and expensive, time-delaying set-ups. He took nearly eight hours to shoot a close-up of Boris Karloff’s face in The Walking Dead. For The Sea Hawk, he added thirty-four unscripted scenes! Unlike Ford and Hitchcock who cut in the camera, Curtiz shot a scene from several angles, resulting inover-coverage.

He was always changing and adding dialogue, which, along with everything else, continually irritated the scholarly Warner Bros. producer of the time, Hal B. Wallis. Almost as prolific as David O. Selznick in his memos, Wallis would cajole, threaten and beg the director to curve his autocratic behavior. “What in the hell is the matter with you and why do you insist on crossing me on everything I ask you not to do?” And each time Curtiz would completely ignore the memo.

Curtiz was the money-maker for Warner Bros., directed eight Humphrey Bogart and twelve Errol Flynn films (making a star of Flynn) and discovered John Garfield, Doris Day, Alexis Smith, Walter Slezak, Danny Thomas and Ann Blyth, among others.

Only half way through the biography, author Rode has ideally encapsulated the artist: “His technical acumen was complemented by an acute awareness of the background details of the stories he was putting on film. . . . Whether it involved a metropolitan newsroom, a small town or an urban slum, his desire to absorb U.S. history and culture would be reflected in the sensibility as well as the reality of his work. Despite his battles with the English language, Curtiz had become a quintessentially American film director.”

Film critic Leonard Maltin concurred: “When one speaks of a typical Warners film in the ’30s and ’40s, one is generally speaking of a typical Curtiz film of those periods.”

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tj7OyiPAyCo[/embedyt]