If for some soldiers the Battle of the Bulge raged on, World War II still continued for others, only now in a POW camp.

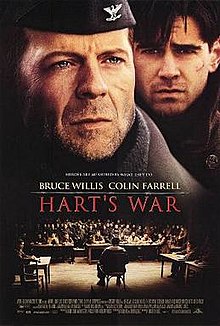

This early in its history, Hart’s War isn’t a classic, and in the years to come it probably won’t become one, but it has a strange appeal, especially for those who might come upon it for the first time, unwarned. The acting is uniformly competent—no complaint there.

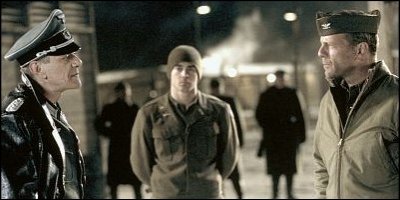

Set in a German POW camp, there is, however, something about the general milieu of the visuals that, if possibly depressing on first viewing, on another examination this seems ideally in keeping with the rest of the film, even a key ingredient in the intended dark and depressing plot and script. Somehow, all put together, everything works.

Of course, in late 1944 Adolf Hitler’s last-ditch Ardennes Counteroffensive—the Battle of the Bulge to most historians—occurred in December, so there is snow on the ground and overcast skies, the ideal “Hitler weather” the madman knew would ground the planes of the RAF and the U.S. Army-Air Force.

So if snow isn’t falling, it’s on the ground and the skies are perpetually gray throughout the film—until the very end. For sure, not an accident.

Not achievable with normal, straightforward cinematography, the film underwent an “adjustment,” possibly a dye transfer, a more than subtle suppression of bright colors, resulting in a consistent, ever-present blue-gray tint. Canadian cinematographer Alar Kivilo’s colors are reminiscent of Russell Boyd’s almost steel-blue hues in Master and Commander (2003) or, in another nautical movie, Moby Dick (1956), where director John Huston deliberately desaturated the colors, then countered the lackluster results by reinforcing the black.

Into this POW camp, with its ambiance of gray melancholy, arrives a freshman soldier. Lt. Thomas Hart (Colin Farrell) was recently captured during the early days of the battle when the Germans were winning, suffering a severe, though short interrogation by the Nazis, short because he gave in to the abuse and pointed to a place on a map, the location of a vital Allied supply site.

Into this POW camp, with its ambiance of gray melancholy, arrives a freshman soldier. Lt. Thomas Hart (Colin Farrell) was recently captured during the early days of the battle when the Germans were winning, suffering a severe, though short interrogation by the Nazis, short because he gave in to the abuse and pointed to a place on a map, the location of a vital Allied supply site.

Hart is greeted, along with a few thousand other American prisoners, by the camp commandant, Col. Werner Visser (Marcel Iures). Speaking perfect English, he demonstrates what happens to prisoners who attempt escape—by hanging several recaptured Russians.

And when Visser refers to them as “dogs” and “animals,” the American officer in charge, Col. William McNamara (Bruce Willis), counters with “My country doesn’t make those kinds of distinctions.” This establishes a racist subplot that, by film’s end, will show that, oh, yes, “his country” does make such distinctions.

In one of the dark and cold barracks—everyone is cold and wears heavy jackets—Hart meets McNamara who asks if he cooperated with the Nazis during his capture. Hart says no; he was interrogated, yes, but only for three days. Although he doesn’t let on, McNamara is suspicious. Only three days? He notices, too, that Hart limps, signs of cruel abuse; McNamara also limps from his own month of torture—but he knows he revealed nothing and wears that as a badge of honor.

In one of the dark and cold barracks—everyone is cold and wears heavy jackets—Hart meets McNamara who asks if he cooperated with the Nazis during his capture. Hart says no; he was interrogated, yes, but only for three days. Although he doesn’t let on, McNamara is suspicious. Only three days? He notices, too, that Hart limps, signs of cruel abuse; McNamara also limps from his own month of torture—but he knows he revealed nothing and wears that as a badge of honor.

McNamara assigns Hart to bunk in a barracks for enlisted men, hardly likely since the Germans assign the prisoners their billeting, and clearly officers and enlisted would not have been mixed.

Into the enlisted men’s barracks come two captured African-American Tuskegee pilots (Tuskegee airmen did not fight in the Ardennes). Immediately hostility erupts in an all-white environment, especially for Sgt. Vic Bedford (Cole Hauser), an open racist. With a planted knife, Bedford frames Lt. Lamar Archer (Vicellous Shannon) who is summarily executed by the Germans, a clear violation, McNamara reminds Visser, of the Geneva Convention. The Nazi counters, “This is not Geneva.”

When Bedford is himself found dead, the second African-American, Lt. Lincoln Scott (Terrence Howard), is accused of the killing.

When Bedford is himself found dead, the second African-American, Lt. Lincoln Scott (Terrence Howard), is accused of the killing.

Hart, a law student before the war, insists to Colonel Visser that the body cannot be moved until photographs are taken and that a court-martial must be held. Visser agrees and ever consents to the use of a barracks for the trial. Impressed with Hart’s legal acumen, McNamara appoints him to defend the pilot.

During a most properly conducted trial—even Nazi guards and Visser are called to testify—Scott speaks eloquently from the stand of the racism he has encountered, how every effort was made to wash him out of flight school, how German POWs in his Alabama hometown were able to eat in diners while he was not. Even Colonel Visser says at one point, “I think your Lieutenant Scott might have been better off in Alabama. A lynching is over in minutes. The kind of justice he’s suffering here is far crueler.”

Hart reveals that Bedford, knowing the guards would kill Archer, had told them of the planted gun, and also about a hidden radio tuned to the BBC, and that he was planning an escape with money and clothes.

McNamara admits to Hart that he killed Bedford, first, to prevent him from escaping and, second, for revealing to the Nazis that an escape is planned. The trial, he says, is a sham, a mere subterfuge to conceal the planned escape and an intended attack on a nearby munitions factory.

McNamara admits to Hart that he killed Bedford, first, to prevent him from escaping and, second, for revealing to the Nazis that an escape is planned. The trial, he says, is a sham, a mere subterfuge to conceal the planned escape and an intended attack on a nearby munitions factory.

Hart is shocked that McNamara would sacrifice Scott for the sake of a military attack. McNamara defends himself, that in war sometimes one man has to die to save many, and that Hart knows nothing about duty, having revealed a military secret after only a three-day interrogation.

At the end of the court-martial, Hart confesses to Bedford’s murder to save Scott. In the meantime, the munitions plant destroyed, McNamara accepts responsibility, volunteering to take the place of the remaining prisoners Visser proposes to execute in retaliation. The Nazi colonel agrees and shots him on the spot.

The Battle of the Bulge won, the war over and the camp liberated, the survivors, including Hart and Scott, depart for home. The camera pans up to what is, finally, for the first time in two hours, a clear, bright sky.

The Battle of the Bulge won, the war over and the camp liberated, the survivors, including Hart and Scott, depart for home. The camera pans up to what is, finally, for the first time in two hours, a clear, bright sky.

Hart’s closing narrative about his learning about duty and honor falls a little flat after all the cross-purposes and deceptions shown by both the Americans and the Germans. While the theme of honor is a little muddled and the plot over-complicated and unclear, the sub-theme of racism is much more forceful, if a bit blunt and uncomfortable at times—as it should be.

Bruce Willis, the uncontested star of Hart’s War, is strong, determined and humorless—as expected. Colin Farrell is excellent, conflicted as his character is. Most of the other actors merge indistinguishably into that shadowy, steel-blue background.

It is Marcel Iures, a Romanian by birth, who is the most fascinating character of the film, perhaps because he isn’t that well known to American audiences.

The screenwriters it seems have tried to make him decent—well, if not that then perhaps . . . likable? He’s certainly intelligent, cultured and well-educated. He holds up a volume of Mark Twain to Hart. “It’s wonderful,” he says. In a number of scenes he appears more than civilized. In one, he emerges from the shadows, and, far from threatening, offers to Hart the body photos he requested. Later, he invites Hart into his office, where it is warm, he says, and gives him a U.S. Army courts-martial manual to assist him in the trial. “We keep a library,” Visser says, “of all American military manuals.”

The screenwriters it seems have tried to make him decent—well, if not that then perhaps . . . likable? He’s certainly intelligent, cultured and well-educated. He holds up a volume of Mark Twain to Hart. “It’s wonderful,” he says. In a number of scenes he appears more than civilized. In one, he emerges from the shadows, and, far from threatening, offers to Hart the body photos he requested. Later, he invites Hart into his office, where it is warm, he says, and gives him a U.S. Army courts-martial manual to assist him in the trial. “We keep a library,” Visser says, “of all American military manuals.”

In another scene, McNamara casually wanders into Visser’s office—impossible that he would have such unguarded freedom (this isn’t Hogan’s Heroes, after all)—and finds the Nazi near-drunk. They talk and Visser puts on the phonograph a shellac recording of Sidney Becker, an African-American saxophonist, playing Gershwin’s “Summertime.” McNamara picks up a revolver from the desk and threatens Visser, then puts it down. All most civilized. But realistic? . . .

Visser delivers one of the best lines in the film: “Strange thing about war wounds—the older you get, the less proud of them you become.” For he, too, limps. And as Leonard Maltin said, “There’s still no villain quite like an urbane, educated Nazi.”

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yOBPV_r4_hs[/embedyt]

Compare ad contrast this flick with : La Grande Illusion”! Almost a century old!

\