A pair of charlatans proves P.T. Barnum quip that there’s a sucker born every minute.

Con artists, tricksters, flim-flam men—examples abound in the movies. Paul Newman, with a vicious pool stick, is one in The Hustler (1961). To determine the reigning con artist of a French Riviera resort, Steve Martin and Michael Caine compete to be first to deprive rich woman Genne Headly of her money in Dirty Rotten Scoundrels (1988). The film was a remake of Bedtime Story (1964) when Marlon Brando and David Niven try much the same with Shirley Jones.

The shyster game works best with partners, as the pairs above prove, and nowhere better than when Michael Sarrazin, AWOL from the U.S. Army, unites with professional swindler George C. Scott in The Flim Flam Man(1967). To suggest that perhaps threesomes aren’t always the best, a lady, Lindsay Crouse, joins Joe Mantegna and Mike Nussbaum in a pigeon drop that goes wrong in House of Games (1987).

But a child as a partner? Sure, why not?

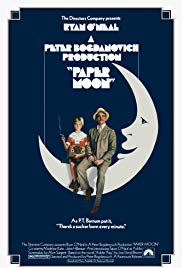

It works in Paper Moon. In Depression-era Kansas, at a funeral for her mother, nine-year-old Addie Loggins (Tatum O’Neal) meets charlatan Bible salesman Moses Pray (Ryan O’Neal). Many of the mourners think he’s the little girl’s fugitive father—and it’s never certain he isn’t. He denies it, but offers to deliver Addie to her aunt in St. Joseph, Missouri.

Thus begins a series of what are more than mere adventures, rather a cavalcade of con slights of hand, wily escapes from the law and, along the way, encounters with a series of odd strangers—a true “road movie” with a different slant.

Thus begins a series of what are more than mere adventures, rather a cavalcade of con slights of hand, wily escapes from the law and, along the way, encounters with a series of odd strangers—a true “road movie” with a different slant.

Paper Moon is among a brief burst of excellent movies in the first half of the ’70s by director Peter Bogdanovich—The Last Picture Show (1971), What’s Up, Doc? (1972) and Nickelodeon (1976). For the director, also a fanatic moviegoer, film historian and interviewer of great directors, these creative explosions were brief indeed. Thereafter, his directorial career was dramatically downhill, concurrent with personal problems. Since the ’70s he has turned more to TV movies.

As an interviewer, Bogdanovich has made friends with any number of the great directors—Roger Corman, Orson Welles and the famously cantankerous John Ford—and done more than his share in illuminating, even stimulating re-evaluations of their careers.

In The Last Picture Show, he made a star of Cybil Shepherd, as well as having an affair with her which ended his first marriage, and directed Ben Johnson toward a Best Supporting Actor Oscar. Ford had seen Johnson’s potential, casting him in at least six of his films, including She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) and Rio Grande(1950), but Bogdanovich used him a little differently.

Before leaving town, Moses stops to convince the brother of the man who accidentally killed Addie’s mother to contribute $200 in support of the new orphan Addie—at first, he had connived unsuccessfully to obtain $2,000. Addie overhears the conversation and later demands her money. Having spent most of the money on repairing the used Model A convertible, Moses agrees for them to travel together until they raise the $200.

Before leaving town, Moses stops to convince the brother of the man who accidentally killed Addie’s mother to contribute $200 in support of the new orphan Addie—at first, he had connived unsuccessfully to obtain $2,000. Addie overhears the conversation and later demands her money. Having spent most of the money on repairing the used Model A convertible, Moses agrees for them to travel together until they raise the $200.

The first of the scams, Moses knocks on several widow’s doors, offering to sell personalized Bibles the late husbands had supposedly ordered before they died. Addie elaborates on the trick, claiming to be his daughter. Her smiling, innocent-girl face works well at deception and Moses thinks she would make a fine partner. In this guise, however, she does refrain from smoking her cigarettes (made from lettuce).

In one masterly collaboration, Moses buys an inexpensive item, gives the clerk (Dejah Moore) $20 and receives his change. Later, Addie as a third or fourth customer, buys some toilet water for twenty-five cents, gives the clerk $5, receives change, then claims she gave the clerk a $20. To prove her assertion, she says her Aunt Helen had written “Happy birthday, Addie” on the bill. When the manager (Ralph Coder) has the clerk check her register drawer, there’s such a bill—the one Moses had left moments ago—and the manager says, “Give the child her $20 bill!”

In one masterly collaboration, Moses buys an inexpensive item, gives the clerk (Dejah Moore) $20 and receives his change. Later, Addie as a third or fourth customer, buys some toilet water for twenty-five cents, gives the clerk $5, receives change, then claims she gave the clerk a $20. To prove her assertion, she says her Aunt Helen had written “Happy birthday, Addie” on the bill. When the manager (Ralph Coder) has the clerk check her register drawer, there’s such a bill—the one Moses had left moments ago—and the manager says, “Give the child her $20 bill!”

Along the way, Moses is captivated by a so-called “exotic dancer,” Miss Trixie Delight (Madeline Kahn), and invites her and her African-American maid Imogene (P.J. Johnson) to join them. Addie becomes friends with Imogene, but is jealous of Moses’ interest in Trixie and is able to frame her in a tryst with the hotel clerk (Burton Gilliam). Moses leaves Trixie and Imogene behind.

At another hotel along the way, Moses finds some bootleg whisky and sells it back to the bootlegger (John Hillerman), unaware that he is the brother of the sheriff (also Hillerman), who arrests them. She steals the keys to their car and using the ruse of having to go to the bathroom, and with Moses to accompany her, and the two escape.

At another hotel along the way, Moses finds some bootleg whisky and sells it back to the bootlegger (John Hillerman), unaware that he is the brother of the sheriff (also Hillerman), who arrests them. She steals the keys to their car and using the ruse of having to go to the bathroom, and with Moses to accompany her, and the two escape.

In a mad chase through country roads, the sheriff in pursuit, Moses takes a detour and discovers a shack and five hillbillies. To elude the sheriff and after a wrestling match with the number one hillbilly (Randy Quaid), Moses exchanges his car for a Model T farm truck.

Finally reaching Missouri, Moses drops Addie off at her aunt’s house in St. Joseph. But, standing on the front porch, Addie realizes she already misses Moses and catches up with him. When he first refuses her company, she reminds him that he still owes her the $200. When their truck begins rolling down the hill, he catches it and helps Addie aboard. They drive off together through a long vista of the unending road, reminiscent of a John Ford scenic landscape.

No coincidence, another Ford admirer, Orson Welles, suggested Bogdanovich shoot in black and white, using a red filter for sharper contrasts.

Behind the main title, “It’s Only a Paper Moon,” sung by Peggy Healy and backed by Paul Whiteman and his orchestra, sets the mood for the era of the 1930s. There are countless songs of the period in the soundtrack, and different radios are tuned to The Jack Benny Program and Fibber McGee and Molly, both big hits in their day. “I have more affection, more affinity for the past,” the director said. “Since I am more interested in it, it comes easier for me.”

Behind the main title, “It’s Only a Paper Moon,” sung by Peggy Healy and backed by Paul Whiteman and his orchestra, sets the mood for the era of the 1930s. There are countless songs of the period in the soundtrack, and different radios are tuned to The Jack Benny Program and Fibber McGee and Molly, both big hits in their day. “I have more affection, more affinity for the past,” the director said. “Since I am more interested in it, it comes easier for me.”

Paper Moon is the second of Bogdanovich’s black and white films—the first was The Last Picture Show, and the second with Ryan O’Neal, after What’s Up Doc?

All the stars do their roles justice. Ryan O’Neal, usually a rather bland actor, is quite effective as the charismatic hustler, Tatum, ten at the time, is a charming little imp and Madeline Kahn uses well her usual shtick of little-girl voices and vocal inflections. John Hillerman, whose first major motion picture had been The Last Picture Show, was required to gain weight for the second dual role as the sheriff.

The apparent on-screen spontaneity and naturalness of the performance of Ryan’s daughter Tatum was not achieved easily. Some scenes required as many as fifty takes. Although she won Best Supporting Actress, Bogdanovich said working with her was “one of the most miserable experiences of my life.”

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ORTv3jORX-I[/embedyt]