“This is called a training circle, a master’s wheel. This circle will be your world, your whole life. Until I tell you otherwise, there is nothing outside of it.”—Don Diego de la Vega to Alejandro Murrieta

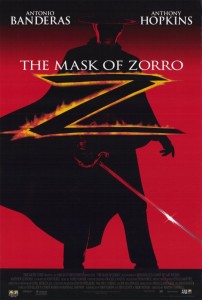

Appearing here, in a website devoted to the “The Golden Age of Hollywood,” the 1998 Mask of Zorro might seem out of place. In certain aspects it is; in other regards it has moments, sparks and intimations of that long-past age of the tongue-in-cheek, over-the-top, make-believe swashbuckler, best exemplified in Errol Flynn’s The Adventures of Robin Hood, Stewart Granger’s Scaramouche and the obvious equivalent, Mask’s seventy-year-old predecessor, Tyrone Power’s The Mark of Zorro.

This latest incarnation of the Mexican Robin Hood legend is a ripsnorter, no doubt about it, with action from the start. Don Diego de la Vega, alias Zorro (Anthony Hopkins), the champion of the peons, harasses his old enemy Don Rafael (Stuart Wilson) during one of his executions. Wilson is a fine villain, with a subtle—very subtle—streak of decency, or maybe it’s only a suspected decency; that subtlety is part of his perverted charm.

Foiled at the firing squad, Don Rafael, however, next invades Don Diego’s hacienda and arrests him, and in the fracas his men accidentally kill Don Diego’s wife and abscond with his baby girl. Don Diego is imprisoned for many years but manages to escape, taking the place of a dead prisoner, being sewn into a shroud sack and buried. Fortunately the grave, per the script, is shallow!

In another part of the forest, or in this case a prickly scrub plain, Alejandro Murrieta (Antonio Banderas) and his brother Joaquin (Victor Rivers) are out thieving, which is their trade, when they are ambushed by a cohort of Don Rafael, Captain Love (Matt Letscher), and his men. Alejandro is taken prisoner and Joaquin is decapitated by Love, who bags the head as a souvenir. Alejandro eventually escapes.

In another part of the forest, or in this case a prickly scrub plain, Alejandro Murrieta (Antonio Banderas) and his brother Joaquin (Victor Rivers) are out thieving, which is their trade, when they are ambushed by a cohort of Don Rafael, Captain Love (Matt Letscher), and his men. Alejandro is taken prisoner and Joaquin is decapitated by Love, who bags the head as a souvenir. Alejandro eventually escapes.

Some time later, at a cantina, Alejandro meets a long- and gray-haired stranger who, after a brief swordfight that Alejandro clumsily loses, says, “When the pupil is ready the master will appear.” The stranger of course is Don Diego, who decides to make a swordsman of the vagrant, teaching him in a hideaway cave. This new Zorro acquires enough of the basics to invade a soldiers’ barracks, masquerade as a priest long enough to take confession from Elena, Don Rafael’s more than lovely daughter (Catherine Zeta-Jones), and do general derring-do. But, with an ulterior motive, Don Diego believes Alejandro needs what he doesn’t have, charm.

Some time later, at a cantina, Alejandro meets a long- and gray-haired stranger who, after a brief swordfight that Alejandro clumsily loses, says, “When the pupil is ready the master will appear.” The stranger of course is Don Diego, who decides to make a swordsman of the vagrant, teaching him in a hideaway cave. This new Zorro acquires enough of the basics to invade a soldiers’ barracks, masquerade as a priest long enough to take confession from Elena, Don Rafael’s more than lovely daughter (Catherine Zeta-Jones), and do general derring-do. But, with an ulterior motive, Don Diego believes Alejandro needs what he doesn’t have, charm.

Don Diego’s idea is to pass off Alejandro as a urbane, Old World aristocrat who seems familiar with the Spanish court and can dazzle the guests at one of Don Rafael’s formal entertainments. Don Diego, complete with serape, Benjamin Franklin glasses and a pigtail, poses as his servant. Alejandro impresses Don Rafael’s vanity enough that the Don welcomes him into his inner circle and its plans to establish the Independent Republic of California—for himself and other would-be aristocrats at the expense of the downtrodden peons. Beyond this, and much to Alejandro’s liking, he also impresses Elena with his dancing—and, yes, with that newly learned charm.

Things round out nicely—nicely in swashbuckler fashion. Don Diego learns that Elena is his own daughter. The big showdown comes at a gold mine. Alejandro kills Captain Love in a long, extravagantly choreographed duel (reminiscent of the 2009 Sherlock Holmes), thus avenging his brother’s death. Although Don Diego and Don Rafael engage in a duel of their own, the villain’s end comes in a macabre death typical of current movies, even those craving a rank with the classics. He is dragged helplessly down a ramp behind a mine cart full of gold, plunging several stories. Splat!

Things round out nicely—nicely in swashbuckler fashion. Don Diego learns that Elena is his own daughter. The big showdown comes at a gold mine. Alejandro kills Captain Love in a long, extravagantly choreographed duel (reminiscent of the 2009 Sherlock Holmes), thus avenging his brother’s death. Although Don Diego and Don Rafael engage in a duel of their own, the villain’s end comes in a macabre death typical of current movies, even those craving a rank with the classics. He is dragged helplessly down a ramp behind a mine cart full of gold, plunging several stories. Splat!

An unavoidable instinct is to compare the film with The Mark of Zorro, putting aside for the moment Douglas Fairbanks, Sr.’s original Mark of Zorro (1920), an outstanding achievement even now. Director Rouben Mamoulian’s pace in the black-and-white 1940/Power version is quick-tempoed—when Zorro is in action: high jacking carriages, posting ultimatums, robbing the tax collectors or, in the end, dueling Captain Pasquale (Basil Rathbone).

In between the action, however, a greater portion of the time than in Mask is devoted to domestic scenes and to humor. The humor, mainly centering around Tyrone Power, is droll but excellent—when Don Diego shows his parents the slight-of-hand tricks he has learned in Madrid, or when he idles away his time waiting to play chess with the good padre (Eugene Pallette)—“It’s a dull game, but what can one do?”—or when he explains to Lolita (Linda Darnell) why he’s late for a dinner: “They heated the water for my bath too early. By the time more water was brought and properly scented—— Life can be trying, don’t you think?”

Tyrone Power, in a sense, is playing three roles—his real character in the beginning, studying horsemanship and fencing in Spain when he is called home by his father; the disguised Zorro defending the peasants and frustrating the authorities; and that other disguise, the foppish idler flourishing scented handkerchiefs instead of swords.

Tyrone Power, in a sense, is playing three roles—his real character in the beginning, studying horsemanship and fencing in Spain when he is called home by his father; the disguised Zorro defending the peasants and frustrating the authorities; and that other disguise, the foppish idler flourishing scented handkerchiefs instead of swords.

Although there is an equal amount of humor in Mask, if a bit more sophisticated, Banderas’ role does not call for the slightly suggestive homosexual façade Power employs. It’s just possible that assuming such a role would not come easily to Banderas, nor that he could play it as well as Power does.

The photography (Phil Meheux) in Mask is excellent, the staging of the stunts as dazzling as any seen on the screen and James Horner’s score is as good, if not better, than Alfred Newman’s for the 1940 version. The one instance, however, where Newman has the edge, hands down, over anything Horner can muster is the romantic, delicately scored music for the scene in the chapel when Lolita begins to suspect that the kindly padre beside her is someone else. Further, the music is equaled by the dramatic chiaroscuro of a truly great cinematographer, Arthur Miller. Yes, so often in that Golden Age everything came together!

Si, the Mask of Zorro and the Mark of Zorro are excellente films, excellente. I watched the Power version in a San Francisco revival…. although I had seen in on TV it was fun to watch on the medium (not big — it was a small theatre) screen. The swordfight finale is, of course, perhaps the best ever filmed. It seemed that many in the audience had never seen it before, because that sequence made they gasp (actually, one guy said, “That’s bad!” And yes, Power’s super fop is very much fun, with classic lines I happen to have forgotten at present; however, I do remember the lines, “Do you think you can handle his sword?” and “Be careful, my dear, or I will have to send you to a convent!” The romance in this film is more appealing than the newer film. However, Banderas makes a fine Zorro, it’s too bad they couldn’t make a third one. I recall that the fencing instructor was the same who had worked with Flynn and all the others, even Rathbone. He said that Banderas was the best natural swordsmen of all the stars, and that he would’ve made a fine one in real life. The score is a great surprise, since movies nowadays don’t seem to have memorable themes. Finally, I must put in a plug for my favorite Zorro, Guy Williams. He had the best costume, had the best physical look and he pronounced “Tornado” as Tor-nah-do, and not Tor-NAY-do like Banderas did (unforgiveable, Senor!) … plus, he had beautiful theme music. Although it was limited by the small screen budget, Guy Williams (Armand Catalano) is the best sst! sst! SST!