“She was a charming middle-aged lady with a face like a bucket of mud. I gave her a drink. She was a gal who’d take a drink, if she had to knock you down to get the bottle.” —a sample of Philip Marlowe’s narration

“She was a charming middle-aged lady with a face like a bucket of mud. I gave her a drink. She was a gal who’d take a drink, if she had to knock you down to get the bottle.” —a sample of Philip Marlowe’s narration

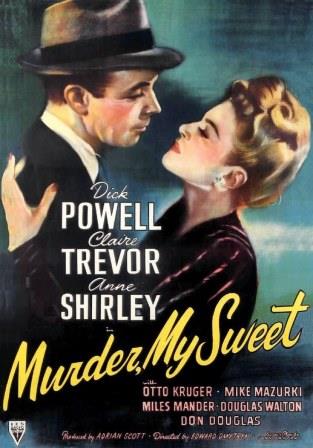

Imagine Humphrey Bogart’s 1941 The Maltese Falcon with Raymond Chandler’s sardonic, hard-boiled narration, with the similes, metonyms and personifications, and you have another classic, almost as good. Murder, My Sweet (1944) may not have Bogart as Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade, but it has Dick Powell as Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, another private detective who walks a fine line between the law and the criminal, also hard, impersonal and unemotional, also viewing the world and the people in it with a certain esoteric cynicism.

Bogart’s status is well known, a screen icon, and The Maltese Falcon ranks high in the litany of cinema greats. In a sense, much like Bogart, who would evolve from the typecast, malevolent gangster into the private detective who, instead of dying at the end of the last reel, now silently gloats over the criminal who does expire, Powell practically reinvented himself, becoming an entirely new man, escaping the musical for a totally different screen genre.

In the 1930s, Powell was well established—too established, he felt—as the romantic, bright-eyed singing lead in countless musicals, also at Bogart’s studio, Warner Bros.—in Gold Diggers of 1933, Footlight Parade, Flirtation Walk and, best of all, 42nd Street. When the studio refused to give him dramatic roles, Powell bought his way out of his contract, first lobbying for the killer of Barbara Stanwyck’s husband in Double Indemnity (1944). Fred MacMurray, making his own image shift away from nice guys, got the part of Walter Neff.

That same year Powell was awarded the lead in Murder, My Sweet as Philip Marlowe, the first actor to play the private eye on screen. The source was Farewell, My Lovely, Raymond Chandler’s second novel about Marlowe—the first was The Big Sleep—but the studio, now RKO, changed the title, fearing audiences might stay away thinking it was a musical.

Although Humphrey Bogart became the quintessential Philip Marlowe in his one and only appearance as the detective in The Big Sleep (1946), Powell holds his own among the best actors who subsequently played the role, including Bogart—among them Robert Montgomery in The Lady in the Lake (1947), James Garner in Marlowe (1969), even Philip Carey in a 1959-60 TV series and, of course, perhaps second only to Bogart, Robert Mitchum in remakes of both the correctly titled Farewell, My Lovely (1975) and The Big Sleep (1978).

Technically, the first Marlowe character appeared in the guise of the Falcon (George Sanders) in The Falcon Takes Over, an adaptation of Farewell, My Lovely. This was in 1942, two years before Powell’s “official” début of the character. Less well known, also in ’42, Lloyd Nolan had stood in for Marlowe, this time pseudonymed as Michael Shayne, in Time to Kill, from Chandler’s The High Window.

Technically, the first Marlowe character appeared in the guise of the Falcon (George Sanders) in The Falcon Takes Over, an adaptation of Farewell, My Lovely. This was in 1942, two years before Powell’s “official” début of the character. Less well known, also in ’42, Lloyd Nolan had stood in for Marlowe, this time pseudonymed as Michael Shayne, in Time to Kill, from Chandler’s The High Window.

Powell, now permanently forsaking singing, takes on dramatic roles and, though, like Bogart, he played Marlowe only once, he maintains his noir image. In 1945, he is reunited with his Murder, My Sweet director, Edward Dmytryk, in Cornered, still a film noir, but now about Nazis in Argentina. Two years later, Powell becomes the title character, a gambling house operator, in Johnny O’Clock, though less of a film than its two predecessors. With director André De Toth, Pitfall (1948) would be another near-great film noir, Powell now an insurance executive who tires of family life and falls under the wiles of a femme fatale (Lizabeth Scott).

One of the actor’s last films, another noir, is Cry Danger (1952), with Powell’s screen wife (Rhonda Fleming) as the woman of suspicion. Soon after, he becomes a director (The Enemy Below [1957], The Hunters [1958]), appears on television and then becomes a TV producer.

One of the actor’s last films, another noir, is Cry Danger (1952), with Powell’s screen wife (Rhonda Fleming) as the woman of suspicion. Soon after, he becomes a director (The Enemy Below [1957], The Hunters [1958]), appears on television and then becomes a TV producer.

The stylish noir quality of Murder, My Sweet has a revealing counterpart—perhaps as a source of inspiration?—in The Maltese Falcon. Dmytryk’s tight and dead-serious direction in Murder, My Sweet is akin to Huston’s, cold and often depressing, the love scenes tenuous and mildly tortured. Harry J. Wild’s cinematography in the Powell film has, too, the same economy of Arthur Edeson’s in Falcon, with only the occasional camera flourish. Read More