The suspense of a man on the edge of a ledge will keep you on the edge of your seat.

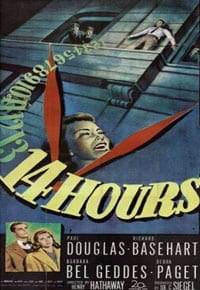

Although he turned more to Westerns toward the end of his career and in the early 1950s displayed his versatility in a cluster of divergent films—a medieval epic that included a sojourn to China, a naval comedy, the obligatory Western, a biography of German general Rommel and a cold war yarn—director Henry Hathaway, in 1951, made a foray into yet another area of motion picture entertainment, the psychological thriller.

The single theme that occupies the entire Fourteen Hours could be summed up in the simple question: Will he or won’t he? Jump, that is.

A young man (Richard Basehart) checks into a room on the fifteen floor of a New York City hotel for the sole purpose of committing suicide. From the ledge outside his room, he keeps busy an array of people working to coax him to come inside.

There is his distraught mother (Agnes Moorehead), not too distraught to reveal her own counterproductive psychoses; the psychiatrist (Martin Gabel) who has Cosick’s problem all figured out, or so he thinks; the over zealous evangelist (George MacQuarrie) who only wants to “save” him, jeopardizing one plan to “save” him in another way; and, most of all, the conscientious and compassionate New York policeman (Paul Douglas) who tries every approach to talk him in, and after he becomes so frustrated he taunts the man to jump, has one last idea.

There is his distraught mother (Agnes Moorehead), not too distraught to reveal her own counterproductive psychoses; the psychiatrist (Martin Gabel) who has Cosick’s problem all figured out, or so he thinks; the over zealous evangelist (George MacQuarrie) who only wants to “save” him, jeopardizing one plan to “save” him in another way; and, most of all, the conscientious and compassionate New York policeman (Paul Douglas) who tries every approach to talk him in, and after he becomes so frustrated he taunts the man to jump, has one last idea.

The tension that saturates the film could have been taken to the extreme, made to last practically forever, with even more characters and any number of contrived subplots—there is, however, one brief and errant foray—but both director Hathaway and screenwriter John Paxton—Murder, My Sweet (1944), Crossfire, (1947), Pickup Alley, (1947), known best for crime dramas and film noirs—maintain a tight rein on the plotting and story.

Those fourteen hours include, of course, what could be called a “night watch” and more clandestine strategies to save the man—search lights, which only frighten him, and a police scheme to lower a man from the roof above in an attempt to grab him, which he spots despite Charlie Dunnigan’s efforts of distraction.

And below, through it all, are the swarm of observers, some who want him rescued and others, typical of the worst in human nature, who want him to jump and provide the entertaining thrill they crave.

Seemingly unconcerned about their duties and unregulated by their bosses, some five NYC cab drivers follow the goings-on, sustained on the sidewalk below with coffee and instantaneous news reports on a portable radio. Bets are even taken on when this guy will jump. The drivers include actors Ossie Davis and Harvey Lembeck.

Seemingly unconcerned about their duties and unregulated by their bosses, some five NYC cab drivers follow the goings-on, sustained on the sidewalk below with coffee and instantaneous news reports on a portable radio. Bets are even taken on when this guy will jump. The drivers include actors Ossie Davis and Harvey Lembeck.

The closest thing to a romance in the film is an accidental meeting in the crowd of two office co-workers, Danny (Jeffrey Hunter, in his film début) and Ruth (Debra Paget). Danny especially works toward some kind of relationship with the initially shy young lady.

Before he first goes to the window, Dunnigan removes his coat, tie and cap, to allay in the man any latent fears of a policeman. Prompted by the psychiatrist, Dunnigan tries unsuccessfully, at least at first, to relate to the man, one human being to another, man to man.

The police discover the nameless stranger is Robert Cosick and locate his mother, who is of little help. The father (Robert Keith) provides only another dead end, as the psychotic mother has instilled in her son a hatred for him. Even when the mother reveals a girl in Cosick’s life, and his estranged fiancée, Virginia (Barbara Bel Geddes), comes to try and talk him in, even this proves fruitless.

The police discover the nameless stranger is Robert Cosick and locate his mother, who is of little help. The father (Robert Keith) provides only another dead end, as the psychotic mother has instilled in her son a hatred for him. Even when the mother reveals a girl in Cosick’s life, and his estranged fiancée, Virginia (Barbara Bel Geddes), comes to try and talk him in, even this proves fruitless.

The one distracting subplot, perhaps the film’s most serious misstep, unfolds in a nearby law office where a woman (Grace Kelly) is about to sign her final divorce papers. After watching the drama on the ledge during the legal proceedings, she decides to reconcile with her husband.

The scene feels “inserted,” a glaring departure from the story line. Kelly’s début in the movies, if that, indeed, was the scene’s sole purpose, went unnoticed by critics. Gary Cooper, on a visit to the set, was sufficiently impressed to suggest Kelly as his wife in the upcoming High Noon (1952).

In the end, Dunnigan does develop the best rapport of any one with his “client,” though at one point frustrated, the policeman says, “I don’t know why I care, but I do.” The rapport is reciprocated. After that hostile encounter with his father, Cosick remarks, “I could never talk to my father the way I’ve talked to you.”

In the end, Dunnigan does develop the best rapport of any one with his “client,” though at one point frustrated, the policeman says, “I don’t know why I care, but I do.” The rapport is reciprocated. After that hostile encounter with his father, Cosick remarks, “I could never talk to my father the way I’ve talked to you.”

Dunnigan seems close to success when he convinces Cosick “to come in, take a shower and think things over. I’ll clear everybody out of the room, give you the key and you can lock yourself in.” When Dunnigan gives his word, Cosick agrees. The room is supposedly cleared, but an overlooked policeman is crouching behind an upholstered chair. Before he can make a move, the evangelist, who has sneaked up the back stairs, rushes into the room. “Kneel and pray! Kneel and pray!” Cosick flees back to the ledge.

By now it is night and once again, somehow, despite the apparent betrayal, Dunnigan has regained Cosick’s trust, now with an invitation to meet his wife—“she’s a good cook”—and take him fishing for flounder on Sheepshead Bay. Cosick is stepping toward the window when a boy on the street below does his impersonation of a skyscraper jumper and accidentally switches on a spotlight. Cosick is distracted, loses his balance and falls. The police had quietly hung a net below the ledge, and Cosick grabs it and is hauled to safety.

While Dunnigan greets his wife and son at the entrance of the hotel, Danny and Ruth, hand in hand, walk away down the dark street.

While Dunnigan greets his wife and son at the entrance of the hotel, Danny and Ruth, hand in hand, walk away down the dark street.

The only musical score heard in the 20th Century-Fox film, by resident composer Alfred Newman, is behind the main title and at the very end, to accompany Hunter and Paget.

Besides Jeffrey Hunter and Grace Kelly, Fourteen Hours provides the film début or second film for many of the extras, including Richard Beymer, John Cassavetes, Joyce Van Patten, Ossie Davis and Harvey Lembeck. Among the up-and-coming stars is Brian Keith, the son of Robert Keith, who plays Cosick’s father.

Like so many Hollywood films, a happy ending replaces the real-life, tragic incident related in Joel Sayre’s story, from which John Paxton fashioned his screenplay. In 1938, a twenty-six-year-old man leaped from the seventeenth floor of the New York City Hotel Gotham. There was no net, no policeman to save him. In a similar tragedy related to the film, the daughter of a Fox executive leaped to her death the day of the film’s preview, prompting a six-month delay in the official release.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rs-dvf0IeeE[/embedyt]