“Captain Thorpe, if you undertook such a venture, you would do so without the approval of the Queen of England, but you would take with you the grateful affection . . . of Elizabeth.”—— Queen Elizabeth I (Flora Robson)

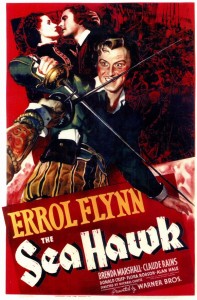

The Sea Hawk, which premiered in 1940, was at least twofold superior to its five-year-earlier predecessor Captain Blood—in sets, script, visual excitement, Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s score, certainly in [intlink id=”34″ type=”category”]Errol Flynn[/intlink]’s acting. Superior except in the presence, nay, the substitution, of Errol Flynn’s love interest. Even among the minor actor-roles, however small, there were some welcomed and familiar carryovers—Fritz Leiber, Pedro de Cordoba, Halliwell Hobbes, Harry Cording, Leonard Mudie and Colin Kenny.

No carryover, unfortunately, in the part of the lovely Doña Maria. [intlink id=”235″ type=”category”]Olivia de Havilland[/intlink] had been scheduled for the role but refused to be yet another wallflower lady-in-waiting for Flynn, and Brenda Marshall filled the vacancy, though hardly “the bill.” At best, Marshall is somewhat tepid and, at times, as in the great reunion love scene in the coach, she appears a little nauseous, as if being cheek to cheek with Flynn was a let-me-get-this-over drudgery. There’s that strange dip in the corners of her mouth. Her performance is the weakest part of the film.

Not to fear. Even with her, The Sea Hawk is one of the great swashbucklers of film history. Director [intlink id=”1579″ type=”category”]Michael Curtiz[/intlink] is perhaps never better in the adventure genre than here, even better than in The Adventures of Robin Hood, also starring Flynn. The original Sea Hawk screenplay by Howard Koch and Seton I. Miller is literate, often moving and humorous, and occasionally poetic.

And this is, hands down, the best of Korngold’s film scores, the last of his four Oscar nominations. His is a key ingredient in the atmosphere of The Sea Hawk, adding appropriate splendor and sweep to the story—the pungent smell of cannon, the pounding horror of a slave galley and the heroic passion the screen lovers sometimes seem hard-pressed to muster.

Unusual for swashbucklers—like comedies, they’ve somehow been judged a lesser breed—The Sea Hawk received three other Oscar nominations besides for score: for sound, special effects and art direction. The sets, like the costumes, were leftovers from The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex the year before. The reuse of the sets was typical of the always cost-conscious Warner Bros., as was the decision to stick with black and white over Technicolor, partly because the recycled battle scenes from several earlier movies, including Captain Blood, were in B&W.

Unusual for swashbucklers—like comedies, they’ve somehow been judged a lesser breed—The Sea Hawk received three other Oscar nominations besides for score: for sound, special effects and art direction. The sets, like the costumes, were leftovers from The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex the year before. The reuse of the sets was typical of the always cost-conscious Warner Bros., as was the decision to stick with black and white over Technicolor, partly because the recycled battle scenes from several earlier movies, including Captain Blood, were in B&W.

The Sea Hawk film bears little resemblance to Rafael Sabatini’s 1915 novel about the Cornish pirate who adopts the name Sakr-el-Bahr, though that character’s servitude on a Spanish slave galley is retained. Rather, apart from the swash and buckle, the film centers on the kind of intrigue in the courts of Spain and England found in Alexander Korda’s Fire Over England(1937). It’s probably because Flora Robson played Queen Elizabeth I so regally in that flick that director Curtiz felt her a natural for his Queen.

Following soon after the heroic main title (Korngold keyed his music to the splashing of the sea against the ship’s prow), Don José Alvarez de Cordoba ([intlink id=”604″ type=”category”]Claude Rains[/intlink]), King Philip II’s ambassador, is sailing to England in a lumbering Spanish galleass. Aboard are his niece, Doña Maria (Marshall), and her maid servant, Miss Latham (Una O’Connor). The oars that help propel the ship are manned by English prisoners. As for the English raiders who menace these waters, Captain Lopez (Gilbert Roland) tells his passenger, “Like hawks, Don Alvarez, they’re on you before you see them.”

Following soon after the heroic main title (Korngold keyed his music to the splashing of the sea against the ship’s prow), Don José Alvarez de Cordoba ([intlink id=”604″ type=”category”]Claude Rains[/intlink]), King Philip II’s ambassador, is sailing to England in a lumbering Spanish galleass. Aboard are his niece, Doña Maria (Marshall), and her maid servant, Miss Latham (Una O’Connor). The oars that help propel the ship are manned by English prisoners. As for the English raiders who menace these waters, Captain Lopez (Gilbert Roland) tells his passenger, “Like hawks, Don Alvarez, they’re on you before you see them.”

Almost at that moment, Captain Geoffrey Thorpe’s (Flynn) ship, the “Albatross,” is sighted (to an impressive blast of a trumpet from EWK). Aided by his fellow privateers—Edgar Buchanan, William Lundigan and Julien Mitchell at the gunwale for a long camera pan—the English defeat the Spaniards in a long, exciting battle. (Please consult a dictionary for the subtle differences between a pirate and a privateer!)

With regal pomp (one of EWK’s finest marches), the sea hawks, including captains played by Robert Warwick and Frank Lackteen, enter the Queen’s throne room. In an argument between Thorpe and Lord Wolfingham (Henry Daniell) over King Philip’s (Montagu Love) cruel treatment of English prisoners, Elizabeth puts on a good show of democratic deference to Spain, but during Thorpe’s private audience, she assumes a quite different posture. Opposed at first, she agrees to his scheme to rob a Spanish gold caravan in Panama. (EWK introduces in the subtlest possible way the Panama march to come.)

With regal pomp (one of EWK’s finest marches), the sea hawks, including captains played by Robert Warwick and Frank Lackteen, enter the Queen’s throne room. In an argument between Thorpe and Lord Wolfingham (Henry Daniell) over King Philip’s (Montagu Love) cruel treatment of English prisoners, Elizabeth puts on a good show of democratic deference to Spain, but during Thorpe’s private audience, she assumes a quite different posture. Opposed at first, she agrees to his scheme to rob a Spanish gold caravan in Panama. (EWK introduces in the subtlest possible way the Panama march to come.)

Doña Maria is by now a little smitten with the captain, though too proud to let him know. When he tells her he will be sailing soon and that he thought he saw “something in your eyes,” she replies that he must be mistaken. (EWK’s music for the rose garden love scene is a jewel, complete with saxophones.)

During a chess game with her uncle (darkly begun by a rising and falling repeated motif in a solo bass clarinet), Doña Maria overhears from spy Kroner (Francis McDonald) a plan to intercept Thorpe in Panama. To warn him, she takes a wild coach ride to Dover—only to be too late: the “Albatross” has sailed on the ebb tide. (EWK gives the two a sumptuous goodbye, recalling a similar moment in Captain Blood, in both cases he gazing back from the ship, she staring out from the dock. Almost the musical climax of The Sea Hawk. But, no, there’s more!)

Thorpe and his men successfully attack the caravan but are later ambushed by the Spanish. The English escape into the swamp. At one point in all this, there’s a short soliloquy from the captain’s first mate (old-time Flynn sidekick Alan Hale) on the irksome mosquito, ending, “The beasts have ears! . . . No, rather have the Spanish.” The crew are captured by Lopez when they reboard the “Albatross.” (For the caravan march, full of percussion beats and taps, EWK uses a theme he had written for a film that never materialized.)

Thorpe and his men successfully attack the caravan but are later ambushed by the Spanish. The English escape into the swamp. At one point in all this, there’s a short soliloquy from the captain’s first mate (old-time Flynn sidekick Alan Hale) on the irksome mosquito, ending, “The beasts have ears! . . . No, rather have the Spanish.” The crew are captured by Lopez when they reboard the “Albatross.” (For the caravan march, full of percussion beats and taps, EWK uses a theme he had written for a film that never materialized.)

The Panama sequences are sepia-toned, which, to some viewers, seems to dull the B&W’s sharpness and soften its contrasts, a choice influenced by the reuse of scenes from the 1924 Sea Hawk, which werealso in sepia.

Back at court, surrounded by the Queen and her ladies in waiting, Doña Maria has finished her song, “My Love Is Far from Me,” when Don José enters to announce that Thorpe and his men have been captured and condemned to the galley. Doña Maria faints. (The German-speaking EWK borrowed from a previous art song, “Das Maedchen,” revising and publishing the film song as “Alt-spanisch,” the third in a set of five art songs, Opus 38.)

Back at court, surrounded by the Queen and her ladies in waiting, Doña Maria has finished her song, “My Love Is Far from Me,” when Don José enters to announce that Thorpe and his men have been captured and condemned to the galley. Doña Maria faints. (The German-speaking EWK borrowed from a previous art song, “Das Maedchen,” revising and publishing the film song as “Alt-spanisch,” the third in a set of five art songs, Opus 38.)

Thorpe and his men escape their chains and take over the galleass and seize the dispatches to Lord Wolfingham about Spanish plans to send an armada against England. They set sail in one of the film’s trademark sequences: “Aloft there! Clear you leech lines . . . clear away your mizzen banks . . . heave tuck your halyards . . . take away your true lines.” (This segues into another Korngoldian climax, now with a male chorus, beginning, “Pull on the oars/Freedom is yours/Strike for the shores of Dover.”)

Arriving at Dover, Thorpe surprises Doña Maria in the coach, and she confesses her love. He must warn the Queen about the armada but is challenged by Wolfingham. Daniell’s ineptitude with the rapier forced the use of a double except in close-ups, and the faster than normal film speed makes for unnatural movement, though it is Flynn’s best fencing sequence. (The supporting music is an EWK tour de force, longer and more complicated than that in The Adventures of Robin Hood.)

Wolfingham dispatched, Captain Thorpe has a reward in store—besides the waiting love of the onlooking Doña Maria, there’s a knighting from the Queen. The scene on the crowded deck of the “Albatross” with the Queen’s canopy might remind some of Peter Paul Rubens’ painting “The Arrival of Mary of Medici at Marseilles.” Like a Baroque painting, the B&W could almost turn to color!

Wolfingham dispatched, Captain Thorpe has a reward in store—besides the waiting love of the onlooking Doña Maria, there’s a knighting from the Queen. The scene on the crowded deck of the “Albatross” with the Queen’s canopy might remind some of Peter Paul Rubens’ painting “The Arrival of Mary of Medici at Marseilles.” Like a Baroque painting, the B&W could almost turn to color!

But abruptly the Queen raises her left hand to still the cheers. The story direction takes a detour. The final, joyous hooray is postponed. First——

The Sea Hawk was released eighteen months before the U.S. entered World War II and while England, already at war, was awaiting an expected onslaught by Adolf Hitler. Warner Bros. was the first Hollywood studio to release an anti-Nazi film, Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939), and the studio wanted to give England whatever encouragement it could. In Elizabeth’s war-time speech just substitute “Hitler” and “Luftwaffe” whenever appropriate: “ . . . to prepare our nation for a war that none of us wants . . . the ruthless ambition of a man threatens to engulf the world . . . we shall make ready to meet this great armada that Philip sends against us . . . ” The speech was cut in the film’s first post-war release but has been subsequently restored.

——The final hurrah from the crowd on the “Albatross” is resumed, not because of Thorpe’s knighthood but, now, because of the Queen’s stirring speech. Everyone is in accord—damn that scoundrel Hitler . . . er . . . Philip. The shouts are then joined by an upsurge from Korngold—the male chorus with “Hail to the Queen!” End cast.

The chunk of Korngold which tends to capture the attention and imagination of the viewer, perhaps because of its length and kaleidoscopic themes, is the sea engagement in the early part of the film. From the sound of that trumpet announcing the sighting of Thorpe’s ship to another trumpet signaling the surrender of the Spanish vessel, the sequence is a dense, ever-changing ten minutes of music. Themes are introduced, they come and go, they are varied. Even the later duel music for Wolfingham and Thorpe is previewed in the brief sword fight between Lopez and Thorpe. Perhaps Thorpe’s theme (the theme that opens the main title) is a bit overused with little variation.

Huh! For a composer who had, at first, turned down The Adventures of Robin Hood because there was too much action—fast tempo requiring so many more notes than slow—Korngold had accepted in The Sea Hawk the most complex, time-consuming assignment of his Hollywood career. So much so that four orchestrators worked day and night to realize EWK’s detailed specifications of instrumentation and effects.

Another rousing, quite different sequence, also with continuous music, is the slaves’ escape from the galley. It’s an exciting nine minutes from the moment Thorpe dislodges the chain that binds the oarsmen to their benches until the sailors finally set sail. All is subtlety, variety and masterful orchestration. It’s actually a suspenseful, long crescendo, disrupted by dramatic outbursts.

Another rousing, quite different sequence, also with continuous music, is the slaves’ escape from the galley. It’s an exciting nine minutes from the moment Thorpe dislodges the chain that binds the oarsmen to their benches until the sailors finally set sail. All is subtlety, variety and masterful orchestration. It’s actually a suspenseful, long crescendo, disrupted by dramatic outbursts.

The orchestra begins quietly, a timid rustling, with only suggestions of a variation on the Thorpe theme. More instruments and other themes are added—now tremolo strings, now an isolated sforzando, now a sustained chord, now a two-note motif in the woodwinds, now brutal fight music—as the slaves loosen their chains, knock out the timekeeper (Art Miles), subdue the guards, struggle with the Spanish messenger (Gerald Mohr). Finally, now with a long-held, major-key chord, a sudden resolution. All the suspense is broken and the men prepare the ship for sea, climaxed by a sailors’ chorus.

Despite these two exciting sequences, perhaps a better, certainly more nuanced scene is Captain Thorpe’s audience with the Queen. First, jokes about his pet monkey (represented, principally, by a xylophone), then some relaxed, almost intimate dialogue, then a gift of a West Indian pearl for the Queen. Their guarded affection is best exemplified in this exchange: “Have you any other scruples?” she asks. “One only, madam—that is to never willfully displease you.” “Have you?” “I trust not. One could be mistaken.”

Despite these two exciting sequences, perhaps a better, certainly more nuanced scene is Captain Thorpe’s audience with the Queen. First, jokes about his pet monkey (represented, principally, by a xylophone), then some relaxed, almost intimate dialogue, then a gift of a West Indian pearl for the Queen. Their guarded affection is best exemplified in this exchange: “Have you any other scruples?” she asks. “One only, madam—that is to never willfully displease you.” “Have you?” “I trust not. One could be mistaken.”

The obvious respect the screen characters have for one another comes from the same mutual esteem the two actors had in real life. In a 1975 interview with Korngold authority Brendan Carroll, Dame Robson remarked, “Errol Flynn was utterly charming . . . I found him to be a total professional, punctual and letter-perfect.” The usually insensitive actor, who hid vodka in skin cleanser bottles and had girls waiting in his dressing room, was aware that Robson’s scenes were being filmed first to accommodate her opening on Broadway, and, as she said, “he had made a special effort on my account.”

Which leads to the inevitable observation: In this scene, there is more charisma, more warmth between these two stars than in any moment between Flynn and Brenda Marshall; in fact, Marshall seems to act better without her co-star—with O’Connor in the rose garden, with Rains after learning of Thorpe’s capture, with Robson in whether to “love” a man or “rule” him.

The Adventures of Robin Hood, it seems,is usually touted as Flynn’s best swashbuckler, giving it an edge over The Sea Hawk, perhaps because of the knowledge, subconsciously, that all those exploits in Sherwood Forest are in Technicolor. No, the best of all Flynn’s films, period, is The Sea Hawk. In each instance, the movie goes a step further than Robin Hood—a superior script, Flynn’s more subtle and nuanced acting, Korngold’s even more expansive music and Sol Polito’s more dynamic cinematography (he did share the camera with Tony Gaudio in the earlier film).

The Adventures of Robin Hood, it seems,is usually touted as Flynn’s best swashbuckler, giving it an edge over The Sea Hawk, perhaps because of the knowledge, subconsciously, that all those exploits in Sherwood Forest are in Technicolor. No, the best of all Flynn’s films, period, is The Sea Hawk. In each instance, the movie goes a step further than Robin Hood—a superior script, Flynn’s more subtle and nuanced acting, Korngold’s even more expansive music and Sol Polito’s more dynamic cinematography (he did share the camera with Tony Gaudio in the earlier film).

Color notwithstanding, the final could-have-been clincher in The Sea Hawk’s supremacy over Robin Hood—perhaps many people would agree—would have been, had Fate deemed otherwise, the inclusion of the greatly missed . . . what was her name? . . . oh, yes: Olivia de Havilland.