“Love’s got to stop sometime, short of suicide.”— Sam Dodsworth

It’s rather early in the history of Hollywood—1936 to be exact—and your memory, if you’re awfully, awfully young, might not go back far enough to recall when this movie was new, or, if you have a meager appreciation of that Golden Age, you may be totally unaware of its existence. The popularity of Dodsworth has, if anything, grown with the years. Oscar-nominated (among ten titles) for Best Picture, it has stood the test of time better than the winner, The Great Ziegfeld. For that matter, Walter Huston’s nominated performance as Sam Dodsworth would now seem, in retrospect, a better choice than the emoting Paul Muni who won for The Story of Louis Pasteur.

Walter Huston was, after all, a “distinguished” actor—how I hate that ambiguity—of some accomplishment. Besides, he was good, great in fact, having played the title role in D. W. Griffith’s Abraham Lincoln, Wyatt Earp in Law and Order, an upright banker in American Madness, a missionary in Rain and an attorney in Star Witness—all performances superior to their respective films, and all before Dodsworth in 1936.

Even the simplicity and openness of his first name, Sam, reveals the nature of the man Dodsworth, a just-retired automobile tycoon. Some of his friends would call him boring, too homespun, not intellectually curious; as once the president of a successful car manufacturing firm, he can’t be dumb. By contrast, his wife, Fran (Ruth Chatterton), to repeat Frank S. Nugent’s adjective-heavy but apt description in the New York Times in 1936, is “a silly, shallow, age-fearing woman of ingrained selfishness and vulgarity.” Sam hasn’t seemed to notice this in twenty years of marriage, perhaps because he’s been a workaholic until now. Suddenly being in close quarters with his wife for long periods, though, might begin to open his eyes.

Even the simplicity and openness of his first name, Sam, reveals the nature of the man Dodsworth, a just-retired automobile tycoon. Some of his friends would call him boring, too homespun, not intellectually curious; as once the president of a successful car manufacturing firm, he can’t be dumb. By contrast, his wife, Fran (Ruth Chatterton), to repeat Frank S. Nugent’s adjective-heavy but apt description in the New York Times in 1936, is “a silly, shallow, age-fearing woman of ingrained selfishness and vulgarity.” Sam hasn’t seemed to notice this in twenty years of marriage, perhaps because he’s been a workaholic until now. Suddenly being in close quarters with his wife for long periods, though, might begin to open his eyes.

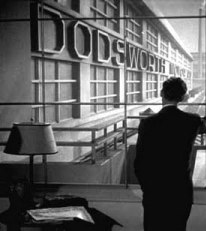

He joins her on an Atlantic cruise to Europe, a second honeymoon. “First time we’ve started out as lovers,” he says, quite excited by the prospects. He discovers the beauty of ocean sunsets and, as they approach England on the last night of the voyage, the Bishop’s Light, which reminds him of his English heritage. Fran hasn’t time or feelings for such, though she reluctantly lets Sam drag her away from her upper crust friends to witness topside the lighthouse beam that swings across the night sky. She can only complain about the cold and her wind-tossed hair.

At about this time Sam enjoys the brief company of fellow passenger Edith Cortright (Mary Astor), recently divorced. Unpretentious and self-assured, she gains Sam’s attention, in an innocent way, a refreshing contrast to Fran. After docking, Mrs. Cortright returns to her home in Italy, while Sam and Fran take a detour to France, since going to England, their original destination, would embarrass the wife after an unfortunate fling with an Englishman, Captain Lockert (David Niven).

At about this time Sam enjoys the brief company of fellow passenger Edith Cortright (Mary Astor), recently divorced. Unpretentious and self-assured, she gains Sam’s attention, in an innocent way, a refreshing contrast to Fran. After docking, Mrs. Cortright returns to her home in Italy, while Sam and Fran take a detour to France, since going to England, their original destination, would embarrass the wife after an unfortunate fling with an Englishman, Captain Lockert (David Niven).

Fran’s “fling” with the captain is limited to her making goo-goo eyes at him and dancing, but when he kisses her she is surprisingly offended, too naïve, perhaps, to realize she has been leading him on. He indignantly responds, “You think you’re a woman of the world and you’re nothing of the sort.”

Sam, who knows both he and Fran are, indeed, unsophisticates, seems strangely unaware, dismissive almost, of his wife’s dalliance. He even calmly refers to Lockert as “fresh but he’s not so bad.” In Sam’s reaction to Fran’s confided humiliation over her romantic melee, he accepts what his wife can’t. “You know,” he tells her, “you and I aren’t up to this sort of thing. Makes us look like the hicks we are.”

Sam, who knows both he and Fran are, indeed, unsophisticates, seems strangely unaware, dismissive almost, of his wife’s dalliance. He even calmly refers to Lockert as “fresh but he’s not so bad.” In Sam’s reaction to Fran’s confided humiliation over her romantic melee, he accepts what his wife can’t. “You know,” he tells her, “you and I aren’t up to this sort of thing. Makes us look like the hicks we are.”

It seems he assumes Fran is as much in love with him as he is with her—and his love for her is reinforced throughout the picture; he more than meets her half way despite her complaining, rudeness toward others, ridicule of him and affectations of culture, flaunting the two French words she knows. So fearful is she of aging that when her daughter has a baby, she asks Sam not to mention it, wishing no one to know she’s a grandmother!

Fran goes further, the film implies, in her next relationship, now with Arnold Iselin (Paul Lukas), living with him beside a Swiss lake. This doesn’t last, but her third affair lands her a marriage proposal from a member of the supposed aristocracy, none other than a baron (Gregory Gaye), and the social status she has craved. She demands a divorce and Sam agrees.

Sam takes a world tour by himself, so much so that every place looks like every other place. In Naples, coincidence of coincidences, he meets again Mrs. Cortright, who invites him to her villa—as she suggests, to fish and sail. Nothing more is suggested, but, well into the twenty-first century, much can be assumed.

As Fran sadly discovers, the baron is not a “free agent.” He must obtain permission to marry from his mother, the baroness (Maria Ouspenskaya), who does not give it. Reasons: for one, the impending divorce and, for another—wouldn’t you know!—the reality Fran has been trying to avoid, deny and camouflage all these years. She’s too old. For what about children, the baroness asks?

As Fran sadly discovers, the baron is not a “free agent.” He must obtain permission to marry from his mother, the baroness (Maria Ouspenskaya), who does not give it. Reasons: for one, the impending divorce and, for another—wouldn’t you know!—the reality Fran has been trying to avoid, deny and camouflage all these years. She’s too old. For what about children, the baroness asks?

Fran finally gets through on the telephone at the Italian villa. Edith had been ignoring and concealing from Sam the persistent calls, but then the maid answers and announces that Mr. Dodsworth has a call from Vienna. Both Sam and Edith know Fran is there. Sam says his wife has dropped the divorce. She needs him and he must go to her. . . . But does he go?

This was Ouspenskaya’s first Hollywood role, and she was nominated for Best Supporting Actress, possibly because of her exotic, diminutive appearance and thick Russian accent. But she lost that year to one of the most bizarre Oscar wins in Hollywood history, to Gale Sondergaard for her grimacing, leering over-acting in Anthony Adverse. Ouspenskaya would be nominated again in 1939 for Love Affair. She does her Maria Ouspenskaya imitation. Aside from the dying grandmother in Kings Row, I remember her best in The Wolf Man, as the gypsy woman who foretells Lon Chaney, Jr.’s transformation into a werewolf.

Director William Wyler was known for both timely and hard-biting pictures, the likes of Dead End, The Best Years of Our Lives, The Heiress, Detective Story, Mrs. Miniver and The Little Foxes. Here as well, Wyler has delivered a highly sophisticated and mature film for its time, one that retains its relevance today. Sidney Howard, who adapted Sinclair Lewis’ novel, was nominated for Best Screenplay. Nominated once before for his work on Arrowsmith (also by Lewis), Howard would not win until 1939 for Gone With the Wind, and then posthumously.

Director William Wyler was known for both timely and hard-biting pictures, the likes of Dead End, The Best Years of Our Lives, The Heiress, Detective Story, Mrs. Miniver and The Little Foxes. Here as well, Wyler has delivered a highly sophisticated and mature film for its time, one that retains its relevance today. Sidney Howard, who adapted Sinclair Lewis’ novel, was nominated for Best Screenplay. Nominated once before for his work on Arrowsmith (also by Lewis), Howard would not win until 1939 for Gone With the Wind, and then posthumously.

Nineteen thirty-six was the second of the great years for Hollywood, following the first, 1935; the pinnacle would come in 1939. Wyler had some justifiably stiff competition among the nominated directors of films that included My Man Godfrey and The Great Ziegfeld, and Frank Capra’s win for Mr. Deeds Goes to Town cannot be contested, wholly different from Dodsworth and more sympathetic to a country deep in the then long-running Great Depression. After all, how many people in 1936 could relate to rich folks who could sail on the “Queen Mary” and live in European villas?

After unsuccessful nominations for Best Actor in 1941 for Mr. Scratch (the Devil) in The Devil and Daniel Webster and for Best Supporting Actor the next year as the father of George M. Cohan in Yankee Doodle Dandy, Walter Huston would have to wait until 1948 for his first and only Oscar. As the grizzly old prospector in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, he was directed by his son John, who also won for Best Director and Best Screenplay.

After unsuccessful nominations for Best Actor in 1941 for Mr. Scratch (the Devil) in The Devil and Daniel Webster and for Best Supporting Actor the next year as the father of George M. Cohan in Yankee Doodle Dandy, Walter Huston would have to wait until 1948 for his first and only Oscar. As the grizzly old prospector in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, he was directed by his son John, who also won for Best Director and Best Screenplay.

The father made one of the most memorable acceptance speeches: “Many years ago . . . , I brought up a boy, and I said to him, ‘Son, if you ever become a writer, try to write a good part for your old man sometime.’ Well, by cracky, that’s what he did!” Memorable acceptance speech or not, it was an even more memorable moment for father and son.