“I’m impatient with stupidity. My people have learned to live without it.” —— Klaatu (Michael Rennie)

War is always with us, it seems, despite the horrors of its continuance, how little it accomplishes and that one war usually results in another. “If we do not end war,” H. G. Wells wrote, “war will end us.” The much earlier British writer Jonathan Swift penned, “War!—that mad game the world so loves to play.” An American, one Mark Twain, wrote, “Man is the only animal that deals in that atrocity of atrocities, War.” Debate, deplore, discourage—it’s all useless: war, like greed and jealousy, is the nature of the beast. The Bible warns that war will always be with us: “Ye shall hear of wars and rumors of wars . . . ”

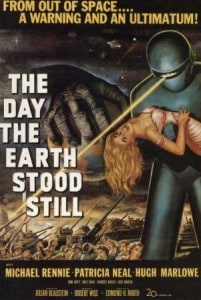

But in a movie anything can happen—and in a movie this dream of a war-free world can come true, or offer that possibility, for The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) is an open-ended film. A representative from a planet that is never identified—only “250 million of your miles away”—arrives in a flying saucer to give the leaders of Earth an ultimatum: “It is no concern of ours how you run your own planet, but if you threaten to extend your violence, this Earth of yours will be reduced to a burned-out cinder.”

Pretty direct, pretty frank.

Patricia Neal, the film’s tentative romantic lead, with a dubious choice between her current beau, an essentially selfish, unpleasant man, and one who is, let’s say, “unattainable,” remarked during filming that she had no idea the movie would become such a hit, have such a cult following or become one of the best science fiction films of all time. It was, perhaps she thought, just one of those space-themed flicks born of the 1950’s, with threats from mutant insects and crustaceans, nuclear radiation, robots gone amok and space aliens.

Patricia Neal, the film’s tentative romantic lead, with a dubious choice between her current beau, an essentially selfish, unpleasant man, and one who is, let’s say, “unattainable,” remarked during filming that she had no idea the movie would become such a hit, have such a cult following or become one of the best science fiction films of all time. It was, perhaps she thought, just one of those space-themed flicks born of the 1950’s, with threats from mutant insects and crustaceans, nuclear radiation, robots gone amok and space aliens.

Director Robert Wise was the film editor on Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons and had to his credit since 1942 a number of wide-ranging directorial efforts: horror (The Body Snatcher, The Curse of the Cat People, with Gunther von Fritsch), film noir (Born to Kill, The House on Telegraph Hill), Westerns (Two Flags West) and straight drama (Three Secrets), though a first comedy, never a favorite genre, would be postponed until Something for the Birds in 1952.

Wise immediately liked the screenplay for The Day the Earth Stood Still when it was submitted to him by Edmund H. North, later one of the screenwriters on Patton. Harry Bates’ original story was first published in Astounding Science-Fiction, as the pulp magazine was titled in 1940. The anti-war theme of the screenplay appealed to Wise, and he believed in intelligences beyond Earth.

Wise immediately liked the screenplay for The Day the Earth Stood Still when it was submitted to him by Edmund H. North, later one of the screenwriters on Patton. Harry Bates’ original story was first published in Astounding Science-Fiction, as the pulp magazine was titled in 1940. The anti-war theme of the screenplay appealed to Wise, and he believed in intelligences beyond Earth.

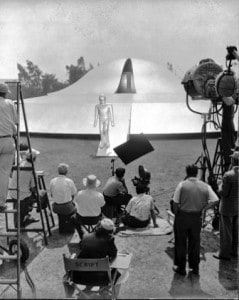

With a few character name changes—the all-powerful robot from Gnut to Gort—and a few plot adjustments, Wise set about to make the film. He was ably assisted by black-and-white cinematographer Leo Tover (The Farmer’s Daughter, The Heiress), film editor William Reynolds (it’s hard to believe Wise himself didn’t help a little!), famous art director Lyle Wheeler, with Addison Hehr, and, not to be forgotten, composer Bernard Herrmann.

Wise had the enthusiastic support of 20th Century-Fox studio head Darryl F. Zanuck, who suggested for the role of the intergalactical messenger Klaatu the British actor Michael Rennie. Because Rennie at the time was unknown to American audiences, Zanuck believed the actor would be most convincing as an alien. Spencer Tracy had been considered, even Claude Rains, who at the time had a Broadway commitment, but both would present familiar faces and greatly diminish the desired effect of a mysterious and exotic extraterrestrial.

Earth producer Julian Blaustine, along with Wise, succeeded in defending Sam Jaffe for the role of Professor Jacob Barnhardt, who is sympathetic to Klaatu’s earthly mission of peace. At the time, the actor was being blacklisted due to the current communist witch-hunts, and after Earth he would be ostracized from motion pictures for some years. Earlier, Jaffe had made a mark as the High Lama in Frank Capra’s Lost Horizon and, at the other extreme of human kind, as master criminal “Doc” Riedenschneider in John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle. Jaffe’s most famous role would come later as Doctor Zorba in the TV medical series Ben Casey, from 1961-1965.

Earth producer Julian Blaustine, along with Wise, succeeded in defending Sam Jaffe for the role of Professor Jacob Barnhardt, who is sympathetic to Klaatu’s earthly mission of peace. At the time, the actor was being blacklisted due to the current communist witch-hunts, and after Earth he would be ostracized from motion pictures for some years. Earlier, Jaffe had made a mark as the High Lama in Frank Capra’s Lost Horizon and, at the other extreme of human kind, as master criminal “Doc” Riedenschneider in John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle. Jaffe’s most famous role would come later as Doctor Zorba in the TV medical series Ben Casey, from 1961-1965.

For the most unusual role of all, though never seen as such, someone tall was needed to be inside the Gort suit, and Lock Martin, at seven feet, seven inches, doorman at Grauman’s Chinese Theater, was recruited. There were problems, though. Martin, not a strong man, was unable to lift and carry the actors the script required and could not remain in the foam rubber suit for more than thirty minutes before experiencing body spasms. My short-term research failed to discover the cause of his unusual height or early death at forty-two. Possibly acromegaly, a disease of the pituitary gland which afflicted actor Rondo Hatton, or possibly Marfan syndrome, which was thought, now generally refuted, to have affected Abraham Lincoln, due to his extremely long limbs.

The Gort suit has its own story. First, there were two suits, one with the zipper in the front and one with the zipper in the back, one or the other suit used depending upon whether Gort is photographed from the front or back. At one point, toward the end of the film when Gort is carrying Neal, actually a dummy, to the spaceship, the seam and zipper can be seen briefly.

The Gort suit has its own story. First, there were two suits, one with the zipper in the front and one with the zipper in the back, one or the other suit used depending upon whether Gort is photographed from the front or back. At one point, toward the end of the film when Gort is carrying Neal, actually a dummy, to the spaceship, the seam and zipper can be seen briefly.

To lend authenticity to this alien invasion, the newscasters who keep the public informed of an incoming flying saucer are played by some well-known personalities of the time: Drew Pearson, H. V. Kaltenborn and Gabriel Heatter.

The alien Klaatu is dressed in a silver suit and a globe helmet when he emerges from the spaceship and announces he has come in peace. When he extends a gift, he is shot in the hand by a nervous soldier, part of a U.S. Army unit that has surrounded the alien machine, and taken to Walter Reed hospital. To Mr. Harley (Frank Conroy), an envoy from the U.S. government, he announces that he wishes to talk to representatives of all the nations of Earth, not to the American president alone or any single government. Harley soon returns—rather soon for so large a task—and declares that, not surprisingly, the nations of the world cannot agree on a single meeting place.

The alien Klaatu is dressed in a silver suit and a globe helmet when he emerges from the spaceship and announces he has come in peace. When he extends a gift, he is shot in the hand by a nervous soldier, part of a U.S. Army unit that has surrounded the alien machine, and taken to Walter Reed hospital. To Mr. Harley (Frank Conroy), an envoy from the U.S. government, he announces that he wishes to talk to representatives of all the nations of Earth, not to the American president alone or any single government. Harley soon returns—rather soon for so large a task—and declares that, not surprisingly, the nations of the world cannot agree on a single meeting place.

Klaatu escapes from the hospital, dons an ordinary business suit, adopts the name Carpenter and takes a room at a boarding house run by Mrs. Barley (Frances Bavier, best known as Aunt Bee in The Andy Griffith Show). The residents include the widow Helen and her son Bobby (Billy Gray from Father Knows Best). After a few visits, Helen’s boyfriend Tom Stevens (Hugh Marlowe) becomes suspicious—and jealous—of Mr. Carpenter, whose intelligence, courtesy and modesty impresses everyone else, including Helen.

When Helen and Tom are away for the day, Bobby gives Carpenter a tour of Washington, D.C. Carpenter is both impressed by the spirit of the Gettysburg Address at the Lincoln Memorial and shocked that most of the graves at Arlington National Cemetery are those of men and women killed in wars. When he asks to meet a great person, Bobby takes him to the home of Professor Barnhardt. The scientist is away, but the visitors easily walk into the house and Carpenter adds an equation to the professor’s blackboard mathematics.

After returning to the boarding house, Carpenter leaves that night and enters the space craft, unaware that Bobby has followed him. Helen and Tom doubt Bobby when he tells them that he saw their new resident disappear inside the flying saucer. When Tom finds a diamond-like rock in Carpenter’s room, he takes it to a jeweler and is told it’s unlike any substance found on earth. Immediately seeing a way to both advance himself and eliminate any possible romantic competition, Tom alerts the authorities and a manhunt is on for the alien.

After returning to the boarding house, Carpenter leaves that night and enters the space craft, unaware that Bobby has followed him. Helen and Tom doubt Bobby when he tells them that he saw their new resident disappear inside the flying saucer. When Tom finds a diamond-like rock in Carpenter’s room, he takes it to a jeweler and is told it’s unlike any substance found on earth. Immediately seeing a way to both advance himself and eliminate any possible romantic competition, Tom alerts the authorities and a manhunt is on for the alien.

Carpenter and Helen are meanwhile caught in a stalled elevator. He explains that he is responsible, for this and a thirty-minute, world-wide electrical failure, except in instances involving human life—hospitals, planes in flight, etc. (Pretty convincing—done in a montage of still photos of the world’s great capitals—but why, pray tell, is that one traffic light lit?!) Carpenter reveals his identify to Helen and asks for help, saying if anything happens to him to alert Gort with the words “Klaatu barada nikto.”

When Carpenter is killed by the military, Helen goes to Gort, who has been standing guard for days beside the saucer. The giant awakens, disintegrates the two guards—only two men guarding the first alien space craft ever to land on earth?!—and is about to turn his deadly ray on Helen when she repeats the three words. He picks her up and takes her inside the saucer, then finds Klaatu and lays him on a device that resurrects him. Klaatu tells Helen that his rebirth is only temporary, though not elaborating on any possible forty-day extension, only that “That power is reserved for the Almighty Spirit.”

When Carpenter is killed by the military, Helen goes to Gort, who has been standing guard for days beside the saucer. The giant awakens, disintegrates the two guards—only two men guarding the first alien space craft ever to land on earth?!—and is about to turn his deadly ray on Helen when she repeats the three words. He picks her up and takes her inside the saucer, then finds Klaatu and lays him on a device that resurrects him. Klaatu tells Helen that his rebirth is only temporary, though not elaborating on any possible forty-day extension, only that “That power is reserved for the Almighty Spirit.”

Before a gathering of the world’s scientists, Klaatu delivers a long speech, ending, “Your choice is simple: join us and live in peace, or pursue your present course and face obliteration. We shall be waiting for your answer. The decision rests with you.” He enters the spaceship for the last time, the craft lifts off and streaks away through the sky.

Robert Wise admitted that, only years later, did he become aware of the Christian overtones in the film. This is more than a little hard to comprehend. Here is this man, Klaatu, who gives himself the name Carpenter—the vocation of Jesus Christ—and arrives to tell the world to do as he says or else, who gives a demonstration of his power and who returns from the dead. Further, surely the religious aspects would have been even more obvious when the Hollywood censors insisted to Wise and screenwriter North that Klaatu’s resurrection, permanent in the original story, now must be only temporary and a line added that any greater power is “reserved for the Almighty Spirit,” which limits the power of Klaatu’s race.

Robert Wise admitted that, only years later, did he become aware of the Christian overtones in the film. This is more than a little hard to comprehend. Here is this man, Klaatu, who gives himself the name Carpenter—the vocation of Jesus Christ—and arrives to tell the world to do as he says or else, who gives a demonstration of his power and who returns from the dead. Further, surely the religious aspects would have been even more obvious when the Hollywood censors insisted to Wise and screenwriter North that Klaatu’s resurrection, permanent in the original story, now must be only temporary and a line added that any greater power is “reserved for the Almighty Spirit,” which limits the power of Klaatu’s race.

The year of Earth, 1951, was a fair year for film scores. That most neglected of Hollywood composers, Alex North—fifteen unsuccessful Oscar nominations—composed that year a groundbreaking jazz score for A Streetcar Named Desire and Dimitri Tiomkin scored The Thing from Another World, a movie similar to Earth in its tie to science fiction, if also in the horror genre. Franz Waxman, a more traditional composer than either North or Tiomkin, wrote that same year some rock-solid dramatic music for A Place in the Sun and won the Oscar.

For years, like North, Bernard Herrmann was overlooked by Academy voters, only in a different way: while North was nominated repeatedly without success, Herrmann was rarely nominated. North’s denial of an Oscar win is still a mystery; Herrmann’s problem may well be his abrasive, indifferent, even rude personality and, most sensitive to those in Hollywood, he made no bones about his dislike for the whole movie crowd.

For years, like North, Bernard Herrmann was overlooked by Academy voters, only in a different way: while North was nominated repeatedly without success, Herrmann was rarely nominated. North’s denial of an Oscar win is still a mystery; Herrmann’s problem may well be his abrasive, indifferent, even rude personality and, most sensitive to those in Hollywood, he made no bones about his dislike for the whole movie crowd.

True, as a beginner in the movie business, he had been nominated in 1941, for two scores, Citizen Kane and All That Money Can Buy, a.k.a. The Devil and Daniel Webster, winning for the latter, and in 1946 for Anna and the King of Siam. For the next twenty years, however, the best of his scores were denied even a nod, much less an award—The Ghost and Mrs. Muir in 1947, The Trouble With Harry in 1955, Vertigo in 1958, Journey to the Center of the Earth in 1959 and, most dumfounding of all, Psycho in 1960, to name a few. In 1977, in an unexpected turnabout, though at the end of his career and his life, he would once again be nominated fortwo scores, Obsession and Taxi Driver. Both lost to Jerry Goldsmith’s The Omen.

Herrmann strove to make each score different from all his others. He sought to assimilate his music into a film by using motifs, four- or five-notes phrases repeated endlessly—all to reflect, almost subliminally, the senses and emotions of the screen, rather than up front with luscious love themes or those stretches of nineteenth-century, pseudo-Germanic complexity characteristic of many European émigrés then working in Hollywood. With this style of thematic economy, simple, if any, counterpoint and limitless repetition, he was one of the earliest minimalist composers, though unrecognized at the time, possibly anteceding Philip Glass, John Adams and their compatriots.

Herrmann strove to make each score different from all his others. He sought to assimilate his music into a film by using motifs, four- or five-notes phrases repeated endlessly—all to reflect, almost subliminally, the senses and emotions of the screen, rather than up front with luscious love themes or those stretches of nineteenth-century, pseudo-Germanic complexity characteristic of many European émigrés then working in Hollywood. With this style of thematic economy, simple, if any, counterpoint and limitless repetition, he was one of the earliest minimalist composers, though unrecognized at the time, possibly anteceding Philip Glass, John Adams and their compatriots.

The Day the Earth Stood Still is clearly Herrmann’s most minimalist score, and his choice of unusual instruments—certainly by Hollywood conventions—would be adopted as among the favorites of the minimalists. The Earth music is most characteristically represented in the use of two theremins, four pianos, two harps, electric organs and amplified strings, including electric guitar, augmented with the more traditional vibraphones, percussion and brass. Besides the absence of woodwinds, also missing is the warmth of violins, violas, cellos and unelectrified double basses.

As Herrmann has said, “My goal was to characterize a man from another world, and the music had to reflect an unearthly feeling of outer space without relying on gimmicks.”

Many of the cues in the score are memorable, to say the least. The main title consists of that very “unearthly feeling” the composer sought. The view of planets, stars and galaxies in endless space is supported by sounds of the signature instruments to follow: the unsettling oscillation of the two theremins, piano arpeggios and the juxtaposition of strange partners, tubas and harps.

The sequence for the radar station that tracks the approaching spacecraft is concentrated mainly in two pianos answering one another in fragments, one in the high treble, the other in the low bass. The latter is reminiscent of a passage in the first movement of Tchaikovsky’s famous Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-Flat Minor.

For Gort the robot, Herrmann wrote for heavy, buzzing brass, erratic timpani rhythms and those ever-present theremins. The musical cues are generally short, but perhaps the longest supports Klaatu’s nocturnal visit to the spaceship. With a flashlight lifted from the boarding house, he signals the silent, motionless Gort, which suddenly comes to life.

For Gort the robot, Herrmann wrote for heavy, buzzing brass, erratic timpani rhythms and those ever-present theremins. The musical cues are generally short, but perhaps the longest supports Klaatu’s nocturnal visit to the spaceship. With a flashlight lifted from the boarding house, he signals the silent, motionless Gort, which suddenly comes to life.

More than thirty years after the film was made, Robert Wise remarked, “I didn’t quite understand what Bernie was talking about [in relation to his music]. But when we got on the music stage and he started to record the cues, I was thrilled. It was beyond anything I had anticipated.” The total music on screen is perhaps little more than twenty-five minutes, but how effective it is! It cannot be underestimated what this score adds to the film.

The visuals and music of The Day the Earth Stood Still are so captivating that the ultimate message of the movie, the end to mindless wars, can be easily overlooked. “If we do not end war, war will end us.” So said that fellow H. G. Welles. But he also added, “Everybody says that, millions of people believe it, and nobody does anything.” Charles Dudley Warner said much the same about another topic, often mistakenly attributed to Mark Twain: “Everybody talks about the weather, but no one does anything about it.”

The visuals and music of The Day the Earth Stood Still are so captivating that the ultimate message of the movie, the end to mindless wars, can be easily overlooked. “If we do not end war, war will end us.” So said that fellow H. G. Welles. But he also added, “Everybody says that, millions of people believe it, and nobody does anything.” Charles Dudley Warner said much the same about another topic, often mistakenly attributed to Mark Twain: “Everybody talks about the weather, but no one does anything about it.”

While mankind, at least as of this writing, cannot change the weather, he could end war—if he wanted to, and had the common sense and humanitarian strength to do so.