“I’ve always felt that I was destined for some great thing, what I don’t know. . . . The last great opportunity of a lifetime—an entire world at war—and I’m left out of it? God will not permit this to happen! I will be allowed to fulfill my destiny. His will be done.” —— General George Patton, during the hiatus following his relief from the U.S. Seventh Army

“I’ve always felt that I was destined for some great thing, what I don’t know. . . . The last great opportunity of a lifetime—an entire world at war—and I’m left out of it? God will not permit this to happen! I will be allowed to fulfill my destiny. His will be done.” —— General George Patton, during the hiatus following his relief from the U.S. Seventh Army

That quote only partially—and very marginally—encapsulates the enigma, the contradictions, that comprised the personality of General George S. Patton, Jr. Despite a high-pitched voice, he was a surprising athlete, a swordsman, equestrian and long-distance runner, a competitor in the 1912 Summer Olympics. From a youngster who had difficulty in reading and writing, he became an avid reader. A religious man who believed in reincarnation, he used coarse language, especially in addressing his troops. “Give it to ’em dirty,” he said. “Then they’ll remember it.”

He grew up in the atmosphere and tradition of the military. His paternal grandfather was a Confederate infantry commander in the American Civil War and a great uncle died in Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg. Although his father desired a military career, he became a lawyer to support his family. George Patton attended the Virginia Military Institute and West Point, and served in World War I as a proponent of tank warfare, though he saw, it’s reported, only a few days of actual combat. It was World War II that would make him famous.

Enough background on the real George S. Patton. What about that one actor who became almost as real in his attempt to capture the essence of this complex, arrogant, profane but brilliant general?

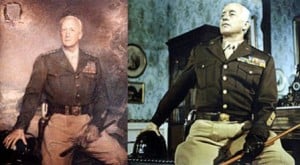

In other instances of perfect casting—the personification of a character in one actor’s performance unimaginable in any other—Vivien Leigh is Scarlet O’Hara, Basil Rathbone becomes Sherlock Holmes and, on a presumed lower level but every bit as masterful, Robert Newton personifies Long John Silver. Some actors wanted the Patton part and were rejected—John Wayne, for one; hard to imagine how Wayne, who proudly boasted he always played himself on screen, could transform and discipline himself into becoming someone else. Burt Lancaster, Rod Steiger and Robert Mitchum were offered the part and turned it down. Imagine, especially, Lancaster in the role, all grinning teeth! Or Steiger: physique wrong, for a start. Mitchum possibly.

With essentially only two exceptional films to his credit at the time, Anatomy of a Murder and Dr. Strangelove, George C. Scott, in hindsight and in up-on-the-screen fact, is the perfect choice, the embodiment of this intense warrior who brought with him, and for the enemy as well, that “terrible swift sword.” Even beyond the full force of the cliché, Scott dominates the screen and—oh, why not another cliché?—he is larger than life. He is in practically every scene, and the screen is his.

With essentially only two exceptional films to his credit at the time, Anatomy of a Murder and Dr. Strangelove, George C. Scott, in hindsight and in up-on-the-screen fact, is the perfect choice, the embodiment of this intense warrior who brought with him, and for the enemy as well, that “terrible swift sword.” Even beyond the full force of the cliché, Scott dominates the screen and—oh, why not another cliché?—he is larger than life. He is in practically every scene, and the screen is his.

The almost three-hour Patton is a true film biography, not a “war movie.” World War II, if anything, is the backdrop for a life, the stage scenery before which moves this exacting, realistic portrait painting come to life. And the life is exactingly “complete” within the relatively brief time scope of the film—no life traversal here—from Patton’s taking command of the defeated and demoralized U.S. II Corps in March, 1943, to his release from command in May, 1945, of the U.S. Third Army. Nothing about earlier—Patton’s command of the Western Task Force that invaded North Africa, nor later—his brief postwar service as Governor of Bavaria and his death on December 21, 1945.

The two screenwriters, Francis Ford Coppola and Edmund H. North, have done an admirable job in transferring to the screen, with basic accuracy and respect, their two literary sources: Ladislas Farago’s Patton: Ordeal and Triumph and General of the Army Omar N. Bradley’s A Soldier’s Story, ghostwritten by his aide de camp Chester B. Hansen.

The two screenwriters, Francis Ford Coppola and Edmund H. North, have done an admirable job in transferring to the screen, with basic accuracy and respect, their two literary sources: Ladislas Farago’s Patton: Ordeal and Triumph and General of the Army Omar N. Bradley’s A Soldier’s Story, ghostwritten by his aide de camp Chester B. Hansen.

Even more than most “war movies,” Patton has its share of technical errors—post-WWII models of Sherman and German tanks, upside down British flags, incorrect military shoulder patches, rifles not used until the Korean War, mistranslations of German subtitles. To offset this, it has more great lines—often funny or poignant—than a dozen movies combined. The plot of the film can be succinctly related, scene by scene, through its signature lines. There are any number of these scenes, many of them so short that they must have been scripted purely for a punch line, most of them delivered by Patton.

Minus the usual 20th Century-Fox logo and Alfred Newman fanfare, the film opens with a five-minute address by Patton to his troops, actually extracts from a number of speeches the general gave. He stands on a stage with a large, splayed American flag behind him. The movie officially begins as Patton watches a parade of Moroccan troops in Rabat and is medaled for his successful landing in North Africa. When asked if he likes Morocco, he responds, “I love it. It’s a combination of the Bible . . . and Hollywood.”

Minus the usual 20th Century-Fox logo and Alfred Newman fanfare, the film opens with a five-minute address by Patton to his troops, actually extracts from a number of speeches the general gave. He stands on a stage with a large, splayed American flag behind him. The movie officially begins as Patton watches a parade of Moroccan troops in Rabat and is medaled for his successful landing in North Africa. When asked if he likes Morocco, he responds, “I love it. It’s a combination of the Bible . . . and Hollywood.”

General Omar Bradley (played by Karl Malden in staunchly low-key fashion appropriate for the subdued character of the man) surveys the battleground after the U.S. II Corps’ defeat at Kasserine Pass, then arrives at his headquarters. To his aid, Colonel Carver (Michael Strong), he says, “Up against Rommel, what we really need is someone tough enough to pull this outfit together.” “Patton?” the aid wonders. “Possibly.” “God help us!”

Patton duly arrives—through the dead of night, with a siren wailing, and finds his new headquarters in drastic need of discipline. Here occurs Patton’s/Scott’s first great line. He rounds a corner and stumbles over a soldier asleep on the floor. The man staggers to attention, saying he was trying to get some sleep. “Well, get back down there, son,” Patton declares. “You’re the only son of a bitch in this headquarters who knows what he’s trying to do.”

Patton duly arrives—through the dead of night, with a siren wailing, and finds his new headquarters in drastic need of discipline. Here occurs Patton’s/Scott’s first great line. He rounds a corner and stumbles over a soldier asleep on the floor. The man staggers to attention, saying he was trying to get some sleep. “Well, get back down there, son,” Patton declares. “You’re the only son of a bitch in this headquarters who knows what he’s trying to do.”

One especially exciting, and at moments comical, scene occurs when General Harry Buford (David Bauer) and the Englishman Air Vice-Marshal Arthur Coningham (John Barrie) meet with Patton. Patton wants to know why there has been no air cover and Coningham assures him he will see no more German planes. At that moment, two Heinkel bombers strafe the upstairs room, and the three men dive under a table. Patton says, “You were discussing air supremacy, Sir Arthur——”

Besides the outside area, the bombers repeatedly strafe the room. While Buford and Coningham are frantic to exit the room—“Damn door won’t open!”—Patton draws his pistol—“By God, that’s enough!”—goes to a window balcony, climbs down to the ground and fires as the planes make further passes. There are several technical and continuity errors in the scene—Patton firing more rounds than his Colt pistol could hold, the bomber passes coming too close together (the planes would need more time to turn around), Buford and Coningham twice dashing to the balcony and Patton’s staff, in the same building, failing to come and check on the safety of their superior.

Besides the outside area, the bombers repeatedly strafe the room. While Buford and Coningham are frantic to exit the room—“Damn door won’t open!”—Patton draws his pistol—“By God, that’s enough!”—goes to a window balcony, climbs down to the ground and fires as the planes make further passes. There are several technical and continuity errors in the scene—Patton firing more rounds than his Colt pistol could hold, the bomber passes coming too close together (the planes would need more time to turn around), Buford and Coningham twice dashing to the balcony and Patton’s staff, in the same building, failing to come and check on the safety of their superior.

After reorganizing his unit, Patton defeats Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s (Karl Michael Vogler) army at the Battle of El Guettar. Looking through his binoculars, he grins and says, “Rommel, you magnificent bastard—I READ YOUR BOOK!” The book had been lying on his cot the night before; an error, Rommel’s never-finished book wasn’t published until much later. After the battle, Patton is told that Rommel was actually in Berlin with an ear infection.

In the first of several references to reincarnation, Patton takes Bradley to an ancient Carthaginian battlefield, describes the two-thousand-year-old battle in great detail and says he was there. Later, while Patton is proposing his strategy against the Germans in Sicily, British general Sir Harold Alexander (Jack Gwillim) suggests, “You know, George, you’d have made a great marshal for Napoleon, if you’d lived in the eighteenth century.” Patton grins and says, “Oh, but I did, Sir Alex, I did.” Everyone laughs.

In the first of several references to reincarnation, Patton takes Bradley to an ancient Carthaginian battlefield, describes the two-thousand-year-old battle in great detail and says he was there. Later, while Patton is proposing his strategy against the Germans in Sicily, British general Sir Harold Alexander (Jack Gwillim) suggests, “You know, George, you’d have made a great marshal for Napoleon, if you’d lived in the eighteenth century.” Patton grins and says, “Oh, but I did, Sir Alex, I did.” Everyone laughs.

Patton is now commanding the U.S. Seventh Army in Sicily and besides the Germans, he is up against that other prima donna of WWII and his rival, Sir Bernard Montgomery (Michael Bates). Patton and the British field marshal—“What, we now have Germans in our army?,” referring to the German military nomenclature—are each in a race for his own fame and glory.

Patton beats him to the city of Palermo, on Sicily’s northwestern coast. At German headquarters, an aid says, “Sir, the Americans have taken Palermo!” General Alfred Jodl (Richard Münch), exclaims, “Damn!” Next shot: a British messenger pulls up to Monty’s command trailer in an American Jeep. “Sir,” he says, “Patton’s taken Palermo!” “Damn!”Montgomery responds. Another vignette obviously included for its humor.

Even Malden as Bradley gets in his best comic line. Under attack from German aerial strafing and losing his helmet, he takes cover moments before a common foot soldier crouches beside him. “What silly son of a bitch is in charge of this operation?” the soldier asks. “I don’t know,” Bradley replies, “but they oughta hang him.”

Even Malden as Bradley gets in his best comic line. Under attack from German aerial strafing and losing his helmet, he takes cover moments before a common foot soldier crouches beside him. “What silly son of a bitch is in charge of this operation?” the soldier asks. “I don’t know,” Bradley replies, “but they oughta hang him.”

In another film snip for the sake of a punch line, Patton is interviewed by a clergyman (David Healy): “I was interested to see a Bible by your bed. You actually find time to read it?” Clearly to shock, but also to further that public image he was cultivating of himself, Patton replies, “I sure do—every goddamn day.”

Patton then beats the British field marshal to Messina, on the eastern side of Sicily. Monty leads his bagpipers into the captured city, only to find Patton and his parade band already there. The two exchange salutes. “Don’t smirk, Patton,” Montgomery says. “I shan’t kiss you.” “Pity,” follows the other. “I shaved very close this morning in preparation for getting smacked by you.”

Patton then beats the British field marshal to Messina, on the eastern side of Sicily. Monty leads his bagpipers into the captured city, only to find Patton and his parade band already there. The two exchange salutes. “Don’t smirk, Patton,” Montgomery says. “I shan’t kiss you.” “Pity,” follows the other. “I shaved very close this morning in preparation for getting smacked by you.”

It is at this time that the famous slapping incident occurs; actually two soldiers were slapped and the episodes were kept hush-hush until broken by journalist Drew Pearson. About the slapped soldier (Tim Considine) shown in the film, Patton yells to the hospital staff, “Take him up to the front! You hear me?! You God-damned coward! I won’t have cowards in my army!” The Nazis, who feared Patton more than any other Allied general, and understood his worth, were amazed that such a successful leader could be censured over, as they saw it, such a trivial matter. The general was relieved of the Seventh Army.

Patton, at first without a command, is finally placed in charge of a fictional army to mislead the Germans into believing the Allied invasion of continental Europe—the D-Day everyone, including the enemy, knew was coming—would be at the Pas de Calais. When Patton is first secreted into London and asks what he is to do in his new command, General Bedell Smith (Edward Binns), one of the planners of the Overload invasion, tells him, “Nothing. Absolutely nothing.”

Patton, at first without a command, is finally placed in charge of a fictional army to mislead the Germans into believing the Allied invasion of continental Europe—the D-Day everyone, including the enemy, knew was coming—would be at the Pas de Calais. When Patton is first secreted into London and asks what he is to do in his new command, General Bedell Smith (Edward Binns), one of the planners of the Overload invasion, tells him, “Nothing. Absolutely nothing.”

When Patton is called to General Bradley’s headquarters in France—this after the successful landings in Normandy—his superior gives him command of the U.S. Third Army. And Patton promptly distinguishes himself and his army, running beyond available maps, leaving his superiors wondering where he is and accomplishing more feats than any other American army in history. “Give George a headline,” Bradley remarks, “and he’s good for another thirty miles.”

During the Battle of the Bulge, Patton asks a chaplain (Lionel Murton) for a “weather prayer” to disperse the inclement weather that has grounded Allied air forces. “I can assure you, sir,” Patton tells the confused clergyman, “because of my intimate relations with the Almighty, if you write a good prayer, we’ll have good weather.”

During the Battle of the Bulge, Patton asks a chaplain (Lionel Murton) for a “weather prayer” to disperse the inclement weather that has grounded Allied air forces. “I can assure you, sir,” Patton tells the confused clergyman, “because of my intimate relations with the Almighty, if you write a good prayer, we’ll have good weather.”

While planning to relieve the pinned-down 101st Airborne Division at Bastogne, a frustrated Patton addresses his staff: “We’re gonna attack all night. We’re gonna attack tomorrow morning. If we are not victorious, let no man come back alive!” When his aid Codman (Paul Stevens) tells him that the men never know when he’s acting, Patton replies, “It’s not important for them to know. It’s only important for me to know.” (Patton was known to practice his anger and scowls before a mirror.)

At one point when Patton is deprived of sufficient gasoline to make what he believes would be a ten-day dash for Berlin, he surveys a desolate battlefield and again reveals his belief in reincarnation. In what amounts to a soliloquy, as Codman mostly nods, he says, “You know how I’m sure [the Germans are] finished out there? The carts—they’re using carts to move their wounded and supplies. Carts came to me in my dream. . . . Now I remembered—that nightmare in the snow, the endless, agonizing retreat from Moscow, how cold it was. . . . Napoleon was finished.” Looking out over the scene, like the climax of a Shakespearian soliloquy, he confesses, “I love it. God help me, I do love it so. I love it more than my life.”

At one point when Patton is deprived of sufficient gasoline to make what he believes would be a ten-day dash for Berlin, he surveys a desolate battlefield and again reveals his belief in reincarnation. In what amounts to a soliloquy, as Codman mostly nods, he says, “You know how I’m sure [the Germans are] finished out there? The carts—they’re using carts to move their wounded and supplies. Carts came to me in my dream. . . . Now I remembered—that nightmare in the snow, the endless, agonizing retreat from Moscow, how cold it was. . . . Napoleon was finished.” Looking out over the scene, like the climax of a Shakespearian soliloquy, he confesses, “I love it. God help me, I do love it so. I love it more than my life.”

At the end of the war, Patton is relieved of the Third Army, in this case for an offhand remark to reporters suggesting that Americans join their political parties much as Germans joined the Nazi Party. After a brief and rather awkward farewell to his staff, he is walking with General Bradley, his bull terrier Willie on a leash, when the wheel of a farm wagon crushes its rock brake and careens toward the men. Bradley pulls him to safety. “After all I’ve been through,” Patton muses, “imagine getting killed by an oxcart. . . . There’s only one proper way for a professional soldier to die—that’s from the last bullet of the last battle of the last war.”

This incident, whether based on fact or not, hints at another vehicle accident that would, indeed, lead to the general’s death. While en route to a pheasant hunt in Germany, Patton was injured in an accident between his 1938 Cadillac staff car and a military truck. His injuries included a broken neck and cervical spinal damage, which caused paralysis below the neck. He died after twelve days in spinal traction and was buried in the Luxembourg American Cemetery, among soldiers of his Third Army, as he had wished.

This incident, whether based on fact or not, hints at another vehicle accident that would, indeed, lead to the general’s death. While en route to a pheasant hunt in Germany, Patton was injured in an accident between his 1938 Cadillac staff car and a military truck. His injuries included a broken neck and cervical spinal damage, which caused paralysis below the neck. He died after twelve days in spinal traction and was buried in the Luxembourg American Cemetery, among soldiers of his Third Army, as he had wished.

George C. Scott would return in 1986 for the TV movie The Last Days of Patton, dealing solely with the general’s dying. A rather depressing, gruesome and pointless drama, Eva Maria Saint portrayed his wife.

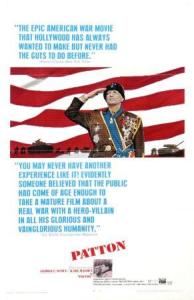

There were three Oscar-nominated war films for 1970. Both Patton and Tora! Tora! Tora! glorified war, while Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H made fun of it. Patton emerged with seven Oscar wins, three at the expense of M*A*S*H. Patton won for Picture, Director (Franklin J. Schaffner), Actor (Scott famously refused the statuette), Adapted Screenplay, Film Editing (Hugh S. Fowler), Art/Set Decoration and Sound.

Jerry Goldsmith’s score, with its sometimes triumphant, sometimes mystically echoing march, was nominated, but strangely lost to Francis Lai for Love Story. That injustice would be partially rectified in 1976 with a win for The Omen, the composer’s only Oscar among eighteen nominations.

Jerry Goldsmith’s score, with its sometimes triumphant, sometimes mystically echoing march, was nominated, but strangely lost to Francis Lai for Love Story. That injustice would be partially rectified in 1976 with a win for The Omen, the composer’s only Oscar among eighteen nominations.

Fred Koenekamp was nominated for his cinematography, but lost to David Lean’s favorite cameraman, Freddie Young, for Ryan’s Daughter.

Patton was the last of two movies photographed in Dimension-150 (the other being John Huston’s The Bible), that is, a 70 mm image with a ratio of 2.2:1, much like the earlier Todd-AO, only with an improved depth of focus and an ultra wide angle. The superiority of this short-lived process is especially impressive in the landscape vistas in Patton—the battlefields at Kasserine and El Guettar, the strafing of the column when Patton shoots the two mules, the tank convoy through the mountain snow and the general’s walk in the desert graveyard, with his confession, “How I hate the twentieth century.”

The idea for Patton had been bounced around Hollywood for a number of years before it finally made the screen, thanks to a number of persistent individuals. The film proved highly successful, making $50,000,000 beyond its initial costs. By contrast, 20th Century-Fox lost $10,000,000 on its Tora! Tora! Tora!, prompting the ousting of studio head Darryl F. Zanuck.

The idea for Patton had been bounced around Hollywood for a number of years before it finally made the screen, thanks to a number of persistent individuals. The film proved highly successful, making $50,000,000 beyond its initial costs. By contrast, 20th Century-Fox lost $10,000,000 on its Tora! Tora! Tora!, prompting the ousting of studio head Darryl F. Zanuck.

Personally—and aren’t all reviews “personal” to a large extent?—Patton has been a difficult film to approach, both objectively as well as with the satisfaction of having done it justice, which I admit I haven’t: I’ve only skimmed the surface. (One omission—now included, obviously!—is the creative use of archival newsreels with the voice of Lowell Thomas, some footage even “recreated” to show, complete with sepia tones and projector streaks, the actor Montgomery saluting and encouraging his troops.)

From among the films that followed after the “glory span” of Hollywood, those unusually extraordinary films between the 1930s and the 1960s, Patton is one of my “most favorite,” if that is grammatically correct. From any decade, Patton is one of the greats, and has all the trappings of “the kinds of films they used to make.”

From among the films that followed after the “glory span” of Hollywood, those unusually extraordinary films between the 1930s and the 1960s, Patton is one of my “most favorite,” if that is grammatically correct. From any decade, Patton is one of the greats, and has all the trappings of “the kinds of films they used to make.”

Besides the qualities that make the film a celluloid masterpiece, some of which I’ve touched upon only marginally, I never forget that Patton it is one of a number of films I watched in a movie theater with my father. Each time I view it, I sense, somehow, being close to him, knowing he saw what I am now seeing. A gentle and decent man, he never swore, or used the slightest off-color language. I had warned him ahead of time that there would be in this film a lot of what he would call “foul language,” but that I wanted him to see it, that it was a stupendous film, that it had a great performance by this actor named George C. Scott.

Dad said something only when it was important, and even sometimes out of desperation, when words became absolutely necessary, so I don’t recall that he passed any specific judgment, certainly not a learned one, for that was not who he was, but I think he thoroughly enjoyed Patton. At least I’ve always believed so.

Dad said something only when it was important, and even sometimes out of desperation, when words became absolutely necessary, so I don’t recall that he passed any specific judgment, certainly not a learned one, for that was not who he was, but I think he thoroughly enjoyed Patton. At least I’ve always believed so.