I’m suggesting Mr President, there’s a military plot to take over the Government of these United States, next Sunday…

The novel (1962) begins in the parking lot of the Pentagon. The movie, released two years later, begins in the rooms of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. But before suspicions of a conspiracy start to unfold, director John Frankenheimer decided to open with some action and improvised a demonstration, which quickly grows into a riot, in front of the White House.

Seven Days In May, based on Fletcher Knebel and Charles W. Bailey II’s novel of the same title, concerns a military plot to take over the United States government, sometime on Sunday, Saturday in the novel.

The film was all too real at the time. The McCarthy scare, with its Congressional hearings and blacklisting, was in the recent past. The Korean War was not that distant a memory, and the Vietnam conflict and the Cold War were ongoing, with the Cuban missile crisis coming in 1962. And still a real threat in the minds of many concerned and knowledgeable citizens was the growing power of the U. S. military.

“Right now the government of the United States is sittin’ on top of the Washington Monument, right on the very point, tippin’ right and left,and ready to fall off and break up on the pavement.”—— Senator Clark

Frankenheimer and screenwriter Ron Serling, having ended his Twilight Zone TV series earlier in 1963, created a dark and realistic scenario, more elaborate and intense than the book. One of the best soliloquies—and the film is full of dramatic speeches—is Serling’s own, of President Lyman identifying the enemy, not the individuals planning to overthrow the government, but “ . . . a nuclear age. It happens to kill man’s faith in his ability to influence what happens to him.”

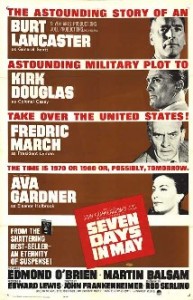

The cast is a high-powered one, the kind of assembly that was waning toward the end of what might be called Hollywood’s post-Golden Age. Burt Lancaster (Elmer Gantry, Birdman of Alcatraz), severe of countenance and with an iron resolve, is Air Force General James Mattoon Scott, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He, along with other military men, a member of Congress and a TV commentator, plans to remove the President due to opposition to a nuclear disarmament treaty.

The cast is a high-powered one, the kind of assembly that was waning toward the end of what might be called Hollywood’s post-Golden Age. Burt Lancaster (Elmer Gantry, Birdman of Alcatraz), severe of countenance and with an iron resolve, is Air Force General James Mattoon Scott, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He, along with other military men, a member of Congress and a TV commentator, plans to remove the President due to opposition to a nuclear disarmament treaty.

Clues suggest that something is amiss—the mention of an unfamiliar military acronym, ECOMCON, an almost indecipherable note, a mysterious Site “Y,” a jittery colonel and, perhaps above all, the seemingly unwarranted importance given to Scott’s request for bets on the upcoming Preakness. These and other irregularities arouse the suspicions of Colonel “Jiggs” Casey (Kirk Douglas, Lust for Life).

Clues suggest that something is amiss—the mention of an unfamiliar military acronym, ECOMCON, an almost indecipherable note, a mysterious Site “Y,” a jittery colonel and, perhaps above all, the seemingly unwarranted importance given to Scott’s request for bets on the upcoming Preakness. These and other irregularities arouse the suspicions of Colonel “Jiggs” Casey (Kirk Douglas, Lust for Life).

“We seem to spend more time training for seizure than for prevention, like the Commies already have the stuff and we have to get it back.”—— Colonel “Mutt” Henderson (Duggan)

Fredric March (The Best Years of Our Lives) plays honest President Jordan Lyman, who is pushing for the treaty. Frankenheimer, bemoaning the drastic change in the country’s values since the days of John F. Kennedy, said he doubted that such an idealistic President could be elected now or, on screen, have much audience sympathy.

Fredric March (The Best Years of Our Lives) plays honest President Jordan Lyman, who is pushing for the treaty. Frankenheimer, bemoaning the drastic change in the country’s values since the days of John F. Kennedy, said he doubted that such an idealistic President could be elected now or, on screen, have much audience sympathy.

Edmond O’Brien (Oscar winner for The Barefoot Contessa) is Raymond Clark, senator from Georgia, accent and folksiness in tact. He struggles to defend his President/friend’s campaign for peace, even going undercover to find that secret base, Site “Y.” When asked by a girl in a desert bar if he wanted to dance, he replies, “No thank you, honey, I just had a hernia operation.”

The love interest—ex-love of General Scott, to be exact—is provided by Ava Gardner, still beautiful at 42, but “sometimes hard to work with,” complained Frankenheimer. Eleanor Holbrook has the general’s love letters which “Jiggs” seeks for the President to use against Scott. (In the final confrontation with the general, however, Lyman has too much integrity to use them, even, it seems, at the possible expense of his presidency.)

The love interest—ex-love of General Scott, to be exact—is provided by Ava Gardner, still beautiful at 42, but “sometimes hard to work with,” complained Frankenheimer. Eleanor Holbrook has the general’s love letters which “Jiggs” seeks for the President to use against Scott. (In the final confrontation with the general, however, Lyman has too much integrity to use them, even, it seems, at the possible expense of his presidency.)

The supporting cast is enriched by Martin Balsam (A Thousand Clowns, Psycho), George Macready (Paths of Glory), Whit Bissell (Hud), Hugh Marlowe (Twelve O’Clock High), Andrew Duggan (Margaret Houlihan’s father in a 1980 M*A*S*H episode) and Richard Anderson (also Paths of Glory). The famous theater/film producer John Houseman makes his acting début as Vice Admiral Farley Barnswell. He alone among the Joint Chiefs declined to place a bet for the Preakness, but attests to his knowledge of the conspiracy in a signed document, which is later temporarily jeopardized.

“Admiral, you’re a very lucky sailor. That’s exactly what I’ve got for you—a sure thing.”—— Paul Girard (Balsam)

The one remaining consummate player in this thoroughly believable and expert film is composer Jerry Goldsmith. David Amram, who had scored Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate, prepared what was unacceptable music and Goldsmith was called in at the last moment. His score adds an unsettling undertow—steel-like chords, fortissimo, for dramatic accent (just one from Law and Order suffices here!) and staccato underpinning for suspense, as when “Jiggs” follows Senator Prentice (Bissell) to the general’s Fort Myer residence and when Clark approaches Site “Y” in his white car across the white sands of the desert.

The one remaining consummate player in this thoroughly believable and expert film is composer Jerry Goldsmith. David Amram, who had scored Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate, prepared what was unacceptable music and Goldsmith was called in at the last moment. His score adds an unsettling undertow—steel-like chords, fortissimo, for dramatic accent (just one from Law and Order suffices here!) and staccato underpinning for suspense, as when “Jiggs” follows Senator Prentice (Bissell) to the general’s Fort Myer residence and when Clark approaches Site “Y” in his white car across the white sands of the desert.

The orchestra, strictly percussion, includes snare drums (the instrument, par excellence, of the military?), xylophones, timpani, orchestral bells and, by all means, one of Jerry’s favorite instruments, the piano, here definitely treated percussively. Goldsmith was to take this hard, metallic approach to the ultimate—less an “undertow,” more a centerpiece—in Planet of the Apes (1967), though thoroughly appropriate to the film, as are all his scores.

As for the Preakness on “Sunday” (it’s always held on Saturday), Frankenheimer relates, in his excellent commentary to the DVD, how he came to near disaster. In starting his film, not on Sunday but with the riot on Monday, he lost a day. “My God!,” he said, “I had a picture suddenly called Six Days In May.” He confided in a friend who suggested that, since the story is set in the future, he photograph a poster advertising “First Running of the Preakness on Sunday,” the new seventh day. Frankenheimer added, “In all the critical analyses that have been written on this picture, that has never come up.”

As for the Preakness on “Sunday” (it’s always held on Saturday), Frankenheimer relates, in his excellent commentary to the DVD, how he came to near disaster. In starting his film, not on Sunday but with the riot on Monday, he lost a day. “My God!,” he said, “I had a picture suddenly called Six Days In May.” He confided in a friend who suggested that, since the story is set in the future, he photograph a poster advertising “First Running of the Preakness on Sunday,” the new seventh day. Frankenheimer added, “In all the critical analyses that have been written on this picture, that has never come up.”

“We’ve all got to stay on the alert these days, Casey—especially on Sunday, right?”—— Senator Prentice

To accommodate the futuristic setting of the film, teleconferencing screens had to be created before they were actually invented. When “Jiggs” sees, on a monitor, his general-boss coming down a hall and Scott suddenly enters the room, all is done in real time, with a second camera feeding the image from the hall. A later teleconference between Lyman and Scott employs the same setup. The backs of the tilted TV sets, for that’s all they were in 1963, are embedded in the table tops.

The sense of “future” cars was accomplished by using only European cars and eliminating American ones. “No one could say,” Frankenheimer commented, “there’s a ’63 Buick.” Well, this approach is not all that convincing, as, for one, Clark’s white car in the desert appears to be a 1963 Chevrolet Nova.

The cinematographer is Ellsworth Fredricks (Friendly Persuasion, the original Invasion of the Body Snatchers). Under the guidance of the director, he achieves some quite impressive shots using wide angle lenses, depth of focus and low angles. Whenever possible, Frankenheimer is keen to keep all the actors in long shots on camera, sometimes “stacking” them, as he said. Close-ups are used sparingly, as they should be. The most effective is the zoom close-up when Casey announces to Lyman, “I’m suggesting, Mr. President, there’s a military plot to take over the government,” followed immediately by the closest possible close-up of the President.

The film is replete with biting, succinct dialogue, refined beyond the book and often created anew by Serling. Casey’s visit with Holbrook to retrieve the love letters is one scene Serling couldn’t get right, and, for a rewrite, the director called in Ned Young (Oscar winner for the original screenplay of The Defiant Ones, 1958). Still, the scene remains somehow unsettlingly, the dialogue awkward. Frankenheimer recalled that here appeared the worst line in any of his films. Holbrook says to Casey, “I’ll make you two promises—a very good steak, medium rare, and the truth, which is very rare.” As an added distraction, the apartment is over lit, without shadows and contrasts, indicative that this is, indeed, a set.

One of the most memorable scenes, however, is the last between Scott and “Jiggs”—pure Serling and not in the novel. The general knows the colonel is the President’s spy who helped bring down his power play.

“You’re a night crawler, a peddler,” Scott says. “You sell information. Are you sufficiently up on your Bible to know who Judas was?”

“I suggest you read that letter, sir,” Casey tells him stoically. “It’s from the President.”

“I asked you a question!” barks the general.

“Are you ordering me to answer, sir?”

“I am!”

“Yes, I know who Judas was. He was a man I worked for and admired until he disgraced the four stars on his uniform.”