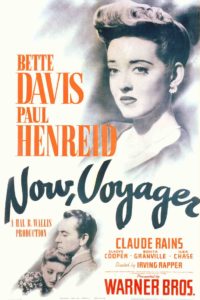

“Oh, Jerry, don’t let’s ask for the moon. We have the stars.” ——Bette Davis to Paul Henreid

Not in Jezebel, certainly not in Dark Victory, nor in Mr. Skeffington, nor in All About Eve, did [intlink id=”228″ type=”category”]Bette Davis[/intlink] appear on screen as anything besides a lovely young lady, usually sophisticated, well-off or famous, or all those things, even, if in the end, there was some kind of retribution. Although much of her early career featured “unattractive” and forgettable roles, it wasn’t until Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, Hush . . . Hush, Sweet Charlotte and The Anniversary, when Bette was no longer in her glory days, that she deliberately allowed herself to be unattractive, either in appearance or in the characters she played, or both.

Now, Voyager came relatively early in those “glory days” when her attractiveness—she was never “beautiful”—was still viable. In this film she does appear shabby, though only briefly. The dowdy appearance is only a setup, for the whole point of the film is her transformation, nay, her metamorphosis.

If one film should be set aside as the ideal of the Davis art—it’s tempting to designate Dark Victory where Death adds poignancy and dramatic challenge—Now, Voyager would be as good a choice as any.

The movie has all the necessary qualities from among the star’s long list of “weepers,” “women’s pictures,” “soapers”—whatever the label—that made her famous. Warner Bros. gives it the full treatment, the top of its A-class films. It was Hal B. Wallis’ first effort as an independent producer and director Irving Rapper’s first Davis film. Rapper would later guide the actress in The Corn Is Green and Deception. Further super-confident support included an appropriately “soapy” script by Casey Robinson, brilliant photography by Sol Polito and a lush score—one of his lushiest—by Max Steiner, Bette’s favorite composer.

Standing in this time for [intlink id=”193″ type=”category”]George Brent[/intlink], her most frequent leading man, is another bland actor, [intlink id=”280″ type=”category”]Paul Henreid[/intlink], just a few months away from the release of Casablanca and his most famous, if not best, role as Nazi fighter Victor Laszlo. Aside from the all-star morale-lifter Hollywood Canteen, Henreid would appear in another Davis film, Deception, and direct her in 1964 in Dead Ringer. He would turn mainly to TV directing in 1957.

Standing in this time for [intlink id=”193″ type=”category”]George Brent[/intlink], her most frequent leading man, is another bland actor, [intlink id=”280″ type=”category”]Paul Henreid[/intlink], just a few months away from the release of Casablanca and his most famous, if not best, role as Nazi fighter Victor Laszlo. Aside from the all-star morale-lifter Hollywood Canteen, Henreid would appear in another Davis film, Deception, and direct her in 1964 in Dead Ringer. He would turn mainly to TV directing in 1957.

Gladys Cooper practically steals the show in a cruelly negative role as a domineering mother, the type of character people love to hate. She artfully avoids the pitfalls of a one-note performance and was justly nominated for a Supporting Oscar. A famous beauty in her youth, she would play, at seventy, another domineering mother to Deborah Kerr in Separate Tables in 1958. In the ’50s and ’60s she did much television, including Playhouse 90, Twilight Zone and The Rogues.

Henreid’s nondescript presence would be offset by the great, always dependable Claude Rains in the sympathetic role of a psychiatrist, dignified, intelligent and humane, practically interchangeable with the one he played almost simultaneously in Kings Row. The supporting cast would include such familiar faces as Mary Wickes, Franklin Pangborn, Lee Patrick, Ian Wolfe and Charles Drake.

All this polish and talent go to create a story about repressed, dowdy spinster Charlotte Vale (Davis), with wire-rimmed glasses, thick eyebrows, hair in skull-hugging marcel waves and wearing cotton dresses and “practical” shoes. She isolates herself in the upstairs bedroom of her mother’s (Cooper) Boston home, compiling scrap books and decorating ivory boxes.

Her sister-in-law (Ilka Chase), unlike the mother, is concerned for Charlotte’s sanity and invites Dr. Jaquith (Rains) to observe her, incognito. In meeting this guest, Charlotte’s descent on the stairs is accompanied by appropriate “descending” music from Steiner, whatever his positives, the master of Mickey-Mousing and tune-borrowing.

Dr. Jaquith asks to be shown around and Charlotte admits him to her room. He engages her in small talk and shows interest in her little boxes. (Disrupting an already interesting scene, the flashbacks of her earlier shipboard romance and the mother’s cruelty, already well established, are somewhat unnecessary.) In Charlotte’s presence, the doctor underplays what he senses and later reveals to her mother the signs of a serious mental illness. He says he believes he can help Charlotte at his sanatorium.

Dr. Jaquith asks to be shown around and Charlotte admits him to her room. He engages her in small talk and shows interest in her little boxes. (Disrupting an already interesting scene, the flashbacks of her earlier shipboard romance and the mother’s cruelty, already well established, are somewhat unnecessary.) In Charlotte’s presence, the doctor underplays what he senses and later reveals to her mother the signs of a serious mental illness. He says he believes he can help Charlotte at his sanatorium.

Recovering quickly, Charlotte becomes an attractive, sophisticated woman—without screen transition, miraculously, like another Immaculate Conception, even. Instead of returning home to her mother, she takes a cruise at Dr. Jaquith’s suggestion. He encourages her with a quote from Walt Whitman: “Now, voyager, sail forth to seek and find.” Aboard ship, she meets Jerry Durrance (Henreid), and from his two traveling companions (Patrick and James Rennie) learns that he is in an unhappy marriage and would divorce his controlling, jealous wife were it not for his love of his young daughter Tina (Janis Wilson, strangely uncredited). (Interestingly, in Bette’s earlier “women’s picture” The Old Maid of 1939, her daughter is named Tina.)

Naturally, Charlotte and Jerry fall in love when, in the ways of these soapers, they are fittingly stranded in Rio de Janeiro and miss their ship, spending time together for several days. Although very sanitized by the Production Code of the day—this was, after all, the early ’40s—they agree not to see each other again. They part at the Rio airport, kissing between cigarette puffs (as everyone smoked in the movies in those days), a rehearsal for the final scene of the movie.

Naturally, Charlotte and Jerry fall in love when, in the ways of these soapers, they are fittingly stranded in Rio de Janeiro and miss their ship, spending time together for several days. Although very sanitized by the Production Code of the day—this was, after all, the early ’40s—they agree not to see each other again. They part at the Rio airport, kissing between cigarette puffs (as everyone smoked in the movies in those days), a rehearsal for the final scene of the movie.

Charlotte’s return home and the dramatic “coming out” of her new persona to family and friends is one of the highlights of the film. Everyone is shocked, surprised and amazed, especially her mother, who is unnerved that her daughter has taken charge of her own life. Desperate to regain control and resentful of her daughter’s new-found independence, Mrs. Vale deliberately falls down the stairs. Even bedridden, she threatens to withdraw Charlotte’s monthly allowance—and inheritance.

Charlotte, not intimidated, becomes engaged to a widower (John Loder, another stiff actor); it is undisclosed if his late wife, or perhaps mother, is also of the dominating persuasion. Their relationship is handled rather perfunctorily, since everyone knows it won’t take. Sure enough, Charlotte, by chance, meets Jerry at a party, and she cancels her engagement, causing another quarrel with her mother, who dies from a heart attack.

Charlotte, not intimidated, becomes engaged to a widower (John Loder, another stiff actor); it is undisclosed if his late wife, or perhaps mother, is also of the dominating persuasion. Their relationship is handled rather perfunctorily, since everyone knows it won’t take. Sure enough, Charlotte, by chance, meets Jerry at a party, and she cancels her engagement, causing another quarrel with her mother, who dies from a heart attack.

Feeling guilty—the power of possessive mothers often endures beyond the grave!—Charlotte returns to the sanatorium and here, again, with the coincidences inherent in these weepers and in the manner of much fiction, she meets Tina. Charlotte sees her former self in the young girl, lonely and with an unloving mother, and takes an interest in her welfare and recovery. She is, after all, Jerry’s child. (If the similarities aren’t obvious enough, the script gives Tina horn-rimmed glasses.)

With Dr. Jaquith’s approval, Charlotte takes Tina home, and when Jerry visits, he is surprised by the change in his daughter and realizes she has found her rightful place with Charlotte. Although the couple cannot ever be together, Charlotte says that Tina is his gift to her, a way she can be close to him. In one of filmdom’s famous scenes, with the two exchanging cigarettes, Jerry asks if she is happy, and she replies with an equally famous line: “Oh, Jerry, don’t let’s ask for the moon. We have the stars.”

Bette Davis, even as the dowdy recluse in need of a makeover, is, well—Bette Davis. Her trademark walk is not so obvious this time, but the arm gestures are. The nervous hands, though no clawing fingers here, recall her queenly role in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex. The typical Davis emerges in the hysterical speech during her first scene with Rains, first, beside the chest-of-drawers and, then, before the rain-dripping window, interestingly with her back to the camera.

Bette Davis, even as the dowdy recluse in need of a makeover, is, well—Bette Davis. Her trademark walk is not so obvious this time, but the arm gestures are. The nervous hands, though no clawing fingers here, recall her queenly role in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex. The typical Davis emerges in the hysterical speech during her first scene with Rains, first, beside the chest-of-drawers and, then, before the rain-dripping window, interestingly with her back to the camera.