“You wanted an ornament, something nice looking to go with the rest of the furniture, brought up the river with great difficulty. Just keep it dusted and see that the termites don’t get at it.” -Joanna Leiningen on being a proxy bride

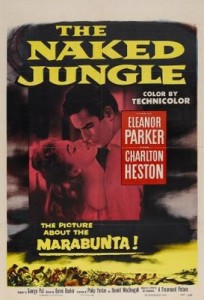

The Naked Jungle (1954) is many things. A love story, if a bit implausible at times. A jungle movie, trek included, with, if not the White Witch Doctor’s tarantula, then a host of ghastly sights for a sometimes bewildered heroine. And, in the climax, a horror flick, but long enough and effective enough to contain some of the film’s best moments. Working toward the semblance of a love story, there’s the initial animosity between Joanna (Eleanor Parker) and Christopher Leiningen (Charlton Heston), how their feelings grow, if not into affection at first, then clearly a mutual forbearance. Their caustic spats are sometimes cutting, sometimes humorous, often at the expense of Christopher, who, in most cases, has met his match.

As to the horror element, this was the 1950s, after all. It was the decade of deadly, mutant, always enormous insects, whether released from an arctic thaw or, as more often, stimulated by inordinate amounts of radiation from atom bomb tests—The Deadly Mantis, Tarantula, The Monster That Challenged the World (crustacean), The Black Scorpion, The Fly (technically a scientist’s mishap) and Them! The last has a direct relevance to The Naked Jungle—the terror of . . . well, what else—ants, in Them! oversized and stressed out, in The Naked Jungle one-inch soldier ants but deadly nonetheless.

The film begins innocently enough, but bits of unsettling dialogue suggest that all is not well, that perhaps herein is the making of a movie. A river boat is traversing the Rio Negro River in 1901. The boat captain (Romo Vincent) asks a lovely young woman (Parker) about her husband. She says she’s on the way to meet him for the first time. The Commissioner (William Conrad)—“commissioner of this area for my government” is the most information he provides—explains that Joanna was married by proxy to Christopher Leiningen, and that he stood in for her at the ceremony. He says her husband owns thousands of acres, a cocoa plantation, just around the river bend.

The captain mentions the strange behavior of the birds, and when Joanna asks the Commissioner—he is never given a name—if he plans to get off at Leiningen’s dock, his reply is hesitant and ominous. “No, I have . . . business further upriver.” At the dock Joanna is met by Incacha (Abraham Sofaer), and when he repeats that he is “Mr. Leiningen’s number one man,” she replies, “And I am Mr. Leiningen’s number one wife. I expected him to meet me here. Where is he?” A rather gritty young lady, this Joanna!

Soon after she settles in at Leiningen’s palatial hacienda, he arrives from the fields. He approaches across a wide walkway and through a long portico, his lowered face further concealed by a broad brimmed hat. Continuing the earlier mystery of his identity, his introduction is dramatically prolonged. The Heston trademarks, the lumbering gait and shoulders twisting puppet-like, befit his naive, defensive awkwardness in meeting Joanna. She suggests he is disappointed in his proxy bride; he replies that she’s . . . just more than he had expected.

Soon after she settles in at Leiningen’s palatial hacienda, he arrives from the fields. He approaches across a wide walkway and through a long portico, his lowered face further concealed by a broad brimmed hat. Continuing the earlier mystery of his identity, his introduction is dramatically prolonged. The Heston trademarks, the lumbering gait and shoulders twisting puppet-like, befit his naive, defensive awkwardness in meeting Joanna. She suggests he is disappointed in his proxy bride; he replies that she’s . . . just more than he had expected.

The first dinner they share is stiff and antagonistic. Joanna tries small talk. His answers are in monosyllables. He does make an observation, in his own crude, rude way, that she is beautiful, sophisticated, speaks French and plays the piano. “I’m not that lucky,” he says, “to get a perfect woman, just like that, out of the grab bag. There must be something wrong with you.” She explains that she’s a widow, that her husband was killed during one of his drinking binges.

After playing the piano with its sour key, she concludes the evening with one of the best lines in the film: “If you knew more about music, you’d realize that a good piano is better when it’s played.” (The viewer can infer here a possible double entendre!) If this isn’t a good enough exit line for a scene, she has one more. As she is leaving the room, he says, “I’m not finished with you, madam”—it is always “madam.” She responds, “Yes you are!” (Like the added first word in “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn,” in Gone With the Wind, a drawn out “Oh-h-h-h—” in front of Joanna’s retort would have provided the rhythm, emphasis and balance to make the line perfect.)

After playing the piano with its sour key, she concludes the evening with one of the best lines in the film: “If you knew more about music, you’d realize that a good piano is better when it’s played.” (The viewer can infer here a possible double entendre!) If this isn’t a good enough exit line for a scene, she has one more. As she is leaving the room, he says, “I’m not finished with you, madam”—it is always “madam.” She responds, “Yes you are!” (Like the added first word in “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn,” in Gone With the Wind, a drawn out “Oh-h-h-h—” in front of Joanna’s retort would have provided the rhythm, emphasis and balance to make the line perfect.)

Leiningen takes her on a horseback ride over his cocoa plantation, and says much toil and suffering is required “so your friends can drink chocolate with their breakfast in New Orleans.” She witnesses the ceremonial execution for adultery of one of his native workers and sees a shrunken head, proudly displayed by a native, a descendent of the Mayans, Leiningen says. “They stayed in the jungle too long.”

The plot changes pace and aspect. The love story intensifies but the jungle and horror elements come into play. When the Commissioner arrives at the hacienda from that “business” he had upriver, he reports that the siji birds and monkeys are mysteriously leaving the Rio Negro basin. Something is chasing them out. It seems that the dormant soldier ants are possibly on the move, for the first time in twenty-seven years—before Leiningen had arrived to clear the jungle and hire eight hundred local natives.