“If someone’s dumb enough to offer me a million dollars to make a picture, I’m certainly not dumb enough to turn it down.”—Elizabeth Taylor

1956! Has it been that long?

Selecting one film that would best represent the career of Elizabeth Taylor, who passed away in March of 2011, is hard indeed, and any choice would arouse countless debates. I’m tempted to listed more than one film—many more than one—that best capture the magic that was Elizabeth Taylor. No, not her beauty: she was beautiful in all her films, though—excuse the digression—I especially remember A Place in the Sun where there is also a seductive, erotic sheen; Elephant Walk when her luminosity resembles a skin-perfect, finely carved ivory cameo; and Ivanhoe when her natural gorgeousness surpasses human logic, as if she were an idealized painting no one could touch.

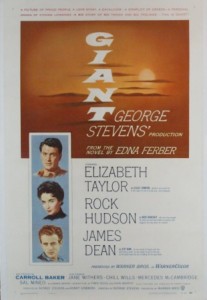

But, yes, it has been that long since 1956 and the release of Giant! And, yes—it’s my pick if I could have only one Elizabeth Taylor film on that fabled Desert Island. Giant is epic, it’s true, and not only an epic picture but an epic Western besides. Conversely, it has a refreshing intimacy, about the two-generation span of a family, with an undertow of jealousies, animosities and out-and-out bickering—just like any family, eh?—and, from both inside and outside of their world, comes all the prejudice and racism of humanity.

But, yes, it has been that long since 1956 and the release of Giant! And, yes—it’s my pick if I could have only one Elizabeth Taylor film on that fabled Desert Island. Giant is epic, it’s true, and not only an epic picture but an epic Western besides. Conversely, it has a refreshing intimacy, about the two-generation span of a family, with an undertow of jealousies, animosities and out-and-out bickering—just like any family, eh?—and, from both inside and outside of their world, comes all the prejudice and racism of humanity.

Elizabeth Taylor has one of her best roles in Giant. Her lifetime trajectory would show, and now in retrospect would prove, that she is playing herself, not always, it must be pointed out, in other films. (The Butterfield 8 role, she insisted, was quite unlike her and she hated the movie.) As for the role of the wife of a Texas cattle, later oil baron, Leslie is totally independent and always herself. “You knew that when you married me,” she tells Bick Benedict (Rock Hudson) during a nightly quarrel, soon dissolved into a night of passion. And so, as a nonfictional, larger-than-life individual, Elizabeth Taylor was equally independent—and always her outspoken, honest self.

Leslie in Giant stepped out of the mold that was made for her, refused to simply fit in and, to use Mrs. Jorgensen’s word in The Searchers, to become a “Texican.” She did the exact opposite and remained herself, genuinely receptive to people. Right off, she was too effusive in meeting the Mexican servants. Before carrying her over the threshold of that enormous house at Reata, Bick had cautioned her not to “make a fuss over those people,” as such relations were against his Benedictian code, against all Texas, it seemed. Then, soon after, in even more of a “fuss,” she tended a sick Mexican baby in an abhorrent “village,” as it was euphemistically called. And, once again, Bick was annoyed that she went there and, worse, that she would suggest that “our doctor” be sent to attend a Mexican.

Like the concerns of Leslie—indeed, the part must have come naturally for the actress—Elizabeth Taylor tended to the needs of AIDS victims through a world-wide charity. The close friendship established on the Giant set between Elizabeth Taylor and co-star Rock Hudson continued until the actor’s death from AIDS, which inspired her cause.

When she was making Giant, her interest in the lives of those around her included not only Rock Hudson but James Dean, the hired hand, Jett Rink, at Reata whose first shot was shared with his old jalopy. His confiding a confidence wasn’t that she was some kind of mother figure to him—she was only one year older—but more likely because, with her rapport with people, she instinctually drew out of him that dark personal secret that he was molested as a child. Moody, stubborn in taking direction and a shy enigma to most members of the cast and crew, James Dean would die in a car accident before the film was released. Elizabeth Taylor was so distraught she missed a day of filming.

On and off any set, Elizabeth Taylor was known for her kindness as well as for her professionalism. When Katharine Hepburn was making Suddenly, Last Summer, I believe it was, and having never worked with Elizabeth Taylor before, she later wrote of expecting a self-centered movie star; instead, she found a conscientious actress who arrived on the set on time, knew her lines and showed concern for her co-workers. Both Katharine Hepburn and Elizabeth Taylor were protective of Montgomery Clift against Suddenly’s malicious director Joseph L. Mankiewicz. By then Clift was a broken man, his face having been severely disfigured several years earlier, in 1956, in a car accident during the filming of Raintree County. His co-star Elizabeth, who had first acted with him in A Place in the Sun and had formed a lasting friendship, was always there to encourage and console him.

On and off any set, Elizabeth Taylor was known for her kindness as well as for her professionalism. When Katharine Hepburn was making Suddenly, Last Summer, I believe it was, and having never worked with Elizabeth Taylor before, she later wrote of expecting a self-centered movie star; instead, she found a conscientious actress who arrived on the set on time, knew her lines and showed concern for her co-workers. Both Katharine Hepburn and Elizabeth Taylor were protective of Montgomery Clift against Suddenly’s malicious director Joseph L. Mankiewicz. By then Clift was a broken man, his face having been severely disfigured several years earlier, in 1956, in a car accident during the filming of Raintree County. His co-star Elizabeth, who had first acted with him in A Place in the Sun and had formed a lasting friendship, was always there to encourage and console him.

In a sense, Giant was Elizabeth’s movie, but there were others, of course, who mixed quite amiably into the brew—some with highly positive results. If the film revealed some of her best acting, it also showed Rock Hudson at possibly his most versatile, although the stuttering, hesitant cowboy who went to Maryland to buy a stallion and came away with the horse as well as a bride, abruptly became the forceful ranch baron once he stepped off the train in Texas. The cast of the film included some important names at the time and others who would later become major stars: Mercedes McCambridge, Paul Fix, Chill Wills, Alexander Scourby, Robert Nichols, Jane Withers, Dennis Hopper, Carroll Baker, Sal Mineo, Earl Holliman and Rod Taylor.

In a sense, Giant was Elizabeth’s movie, but there were others, of course, who mixed quite amiably into the brew—some with highly positive results. If the film revealed some of her best acting, it also showed Rock Hudson at possibly his most versatile, although the stuttering, hesitant cowboy who went to Maryland to buy a stallion and came away with the horse as well as a bride, abruptly became the forceful ranch baron once he stepped off the train in Texas. The cast of the film included some important names at the time and others who would later become major stars: Mercedes McCambridge, Paul Fix, Chill Wills, Alexander Scourby, Robert Nichols, Jane Withers, Dennis Hopper, Carroll Baker, Sal Mineo, Earl Holliman and Rod Taylor.

There was also the team of director George Stevens and cinematographer William C. Mellor, and both had worked with Elizabeth Taylor in A Place in the Sun. Mellor had won an Oscar for A Place in the Sun, but surprisingly was not nominated for Giant, although 1956 was an unusually tight year for Oscar-nominated color cinematographers, with Leon Shamroy, Harry Stradling, Jack Cardiff, Lionel Lindon and Loyal Griggs. Of the ten nominations accorded Giant, Stevens was the only Oscar winner, and his only other directorial win was, coincidentally, for A Place in the Sun.

It was Stevens and Mellor who gave Giant its visual sweep. Stevens’ preference for an unencumbered high screen over the wide CinemaScope ratio then in vogue comes though in the many scenes with extraordinary vistas of sky and open plain. There were, however, other occasions when the wider screen would have been an advantage, say, when Jett paces off his newly acquired land, complete with oil derrick. For me, this is one of the most memorable scenes in the film; it was somewhat improvisational, as neither director nor cameraman knew exactly what the unfettered James Dean would do.

It was Stevens and Mellor who gave Giant its visual sweep. Stevens’ preference for an unencumbered high screen over the wide CinemaScope ratio then in vogue comes though in the many scenes with extraordinary vistas of sky and open plain. There were, however, other occasions when the wider screen would have been an advantage, say, when Jett paces off his newly acquired land, complete with oil derrick. For me, this is one of the most memorable scenes in the film; it was somewhat improvisational, as neither director nor cameraman knew exactly what the unfettered James Dean would do.

This long walk, with Jett’s hesitations, his stops and starts, his checking a fence and his climbing to the top of a windmill, is accompanied by the appropriate, open-air music of Dimitri Tiomkin, the Western film composer par excellence. Christopher Palmer, the late film music critic and record producer, called the principal theme of Giant, accompanied by a chorus in the main title, “surely one of the grandest tunes ever written, on screen or off.”

This long walk, with Jett’s hesitations, his stops and starts, his checking a fence and his climbing to the top of a windmill, is accompanied by the appropriate, open-air music of Dimitri Tiomkin, the Western film composer par excellence. Christopher Palmer, the late film music critic and record producer, called the principal theme of Giant, accompanied by a chorus in the main title, “surely one of the grandest tunes ever written, on screen or off.”

In retrospect, certain scores, quite by accident at the time, now seem ideally suited to their films, unimaginable with any other music—Bernard Herrmann’s Psycho, Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s The Adventures of Robin Hood, Franz Waxman’s Sunset Blvd. and Miklós Rózsa’s Ben-Hur, to name the most obvious. Likewise, Giant is inconceivable without Tiomkin’s music—and the film is made all the better for it.

Surprisingly, Elizabeth Taylor was not nominated for Leslie Benedict in Giant, although the following year would begin four years of consecutive nods for Best Actress. And that last year she won for the role of a call girl in Butterfield 8, possibly the least deserving of the four nominations that comprised Raintree County, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Suddenly, Last Summer and Butterfield 8. She would be nominated only once more, and as a winner, in 1966 for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? In 1993, she would deservedly receive the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award.

Giant has been called by some critics a bloated, over-long bore, with more than an unpleasant whiff of soap opera, but I think not. It was made, it should be remembered, at a time when movies unfolded at a leisurely, one might say, “natural” pace; back then, time was needed to tell a story—when there was a story!—and to introduce and develop the characters, and make them real. Explosions, gun battles, car chases, special effects, fist fights (though there are some in Giant!), illogical body movements, unrealistic fantasy worlds were absent; today these are, unfortunately, public-demanded ingredients of movie-making. Maybe, someday, the best in the movies will return, as will the pleasurable experience of being truly entertained in a darkened theater, when people will actually “enjoy” watching a movie and audiences will be courteous, cell phones nonexistent.

But, then, all that’s doubtful. Just as it is doubtful—highly doubtful—that such a personality, such a beauty, such an original as Elizabeth Taylor, with her universal magnetism, will ever appear on the screen again. On the day of her death, she was already being proclaimed as the last star of the movie’s much fabled Golden Age, so fabled, in fact, that many people don’t believe it ever existed. Many times in the past that “last” accolade has been misappropriated for other stars’ deaths. Not this time, I assure you. Elizabeth Taylor was, indeed, one of a kind.

But, then, all that’s doubtful. Just as it is doubtful—highly doubtful—that such a personality, such a beauty, such an original as Elizabeth Taylor, with her universal magnetism, will ever appear on the screen again. On the day of her death, she was already being proclaimed as the last star of the movie’s much fabled Golden Age, so fabled, in fact, that many people don’t believe it ever existed. Many times in the past that “last” accolade has been misappropriated for other stars’ deaths. Not this time, I assure you. Elizabeth Taylor was, indeed, one of a kind.