“You risk your skin catching killers and the juries turn them loose so they can come back and shoot at you again.”— Lon Chaney, Jr. to Gary Cooper

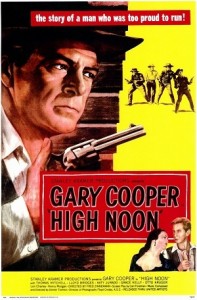

High Noon was a new Western for its time, a more accurate image of the real Old West and away from the picturesque, blue-skied (black and white or not), clearly sanitized view that had started, in a way, with that first Western, The Great Train Robbery (1903), and had persisted with The Squaw Man (1914), The Iron Horse (1924), The Plainsman (1936) and Stagecoach (1939). A striving for the authentic nineteenth-century West had been suggested perhaps as early as [intlink id=”1692″ type=”category”]John Ford[/intlink]’s My Darling Clementine (1946) and by Howard Hawks, another no-nonsense director, in Red River (1948). In 1950 came a further de-glamorization—the tragic end of a gunslinger who tried to escape his past—in [intlink id=”8949″ type=”post”]The Gunfighter[/intlink] three years before High Noon.

Director Fred Zinnemann, an Austrian who would later reinforce his affinity for Westerns with Oklahoma! (though hardly “realistic”) and The Sundowners (albeit set in Australia), was ably supported by cinematographer Floyd Crosby and another émigré, Russian composer Dimitri Tiomkin. Working together to create an unadorned, even austere visual image of the Old West, the three men made High Noon what it is, one of the greatest Westerns of all time.

Not always discernible from this sixty-year-later perspective, High Noon was very much a product of its time, containing overtones of a then relevant political message—prompted by the beginnings of the McCarthy Communist scare and the subsequent House Un-American Activities Committee: the nation, and Hollywood in particular, like the citizenry of 1870s High Noon, must unite against a common evil. But will they? If not, why didn’t they?

Perhaps to no surprise, the film’s producer, Stanley Kramer, was the personified “message” producer/director, i.e., The Defiant Ones (a friendship between a black man and a white man), On the Beach (nuclear holocaust), [intlink id=”9071″ type=”post”]Inherit the Wind[/intlink] (evolution versus religious fanaticism) and Judgment at Nuremberg (Nazi crimes against humanity). Even Kramer’s supposed comedy Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner was about racial intermarriage, though, unlike the aforementioned films, treated lightly—at times awkwardly—but essentially a simplistic view without much consideration of the possible consequences, particularly at the time of its release, the mid-’60s.

Perhaps to no surprise, the film’s producer, Stanley Kramer, was the personified “message” producer/director, i.e., The Defiant Ones (a friendship between a black man and a white man), On the Beach (nuclear holocaust), [intlink id=”9071″ type=”post”]Inherit the Wind[/intlink] (evolution versus religious fanaticism) and Judgment at Nuremberg (Nazi crimes against humanity). Even Kramer’s supposed comedy Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner was about racial intermarriage, though, unlike the aforementioned films, treated lightly—at times awkwardly—but essentially a simplistic view without much consideration of the possible consequences, particularly at the time of its release, the mid-’60s.

In High Noon, the camera of Floyd Crosby, more often associated with many of the Roger Corman/Edgar Allan Poe horror films, gives the film its stark look. As there is no humor to speak of in the script, so there is none in the photography. Shots of the sky are unfiltered; in fact, there are no clouds, only a drab, solid gray sky. Even the final prints were made a few points lighter than normal, done intentionally to emphasize the bleakness. No film noir shades and shadows here.

Sky is often avoided in the many shots of the streets, streets that are almost always empty. It could be that everyone is in church, as there is one long scene to justify that, but everybody can’t be at the service—not the little boys the marshal meets in the street, or the ex-marshal, or the town drunk who volunteers to help, or the few others, certainly not the four gunslingers who’ve come to kill the marshal. Which is what the film is all about.

The plot is simplicity itself. On his wedding day, Marshal Will Kane ([intlink id=”900″ type=”category”]Gary Cooper[/intlink]) is hanging up his badge and leaving Hadleyville with his new wife ([intlink id=”275″ type=”category”]Grace Kelly[/intlink]). During the congratulations, he learns that Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald), an outlaw he had sent to prison, has been pardoned and is due in on the noon train to extract revenge. Citizens report seeing three of Miller’s former gang (Lee Van Cleef in his film début, Robert J. Wilke and Sheb Wooley) riding into town, apparently to rendezvous with Miller.

The plot is simplicity itself. On his wedding day, Marshal Will Kane ([intlink id=”900″ type=”category”]Gary Cooper[/intlink]) is hanging up his badge and leaving Hadleyville with his new wife ([intlink id=”275″ type=”category”]Grace Kelly[/intlink]). During the congratulations, he learns that Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald), an outlaw he had sent to prison, has been pardoned and is due in on the noon train to extract revenge. Citizens report seeing three of Miller’s former gang (Lee Van Cleef in his film début, Robert J. Wilke and Sheb Wooley) riding into town, apparently to rendezvous with Miller.

A few miles out of town, Kane turns the buckboard around and returns: He can’t. He’s never run before. It’s not right. Perhaps, with a party of deputies, everything will work out. Maybe there won’t be any trouble.

It seems that some people aren’t going to hang around to find out. The judge (Otto Kruger) who sentenced Miller packs his judicial necessities in his saddlebags and rides away, suggesting Kane do the same: “This is just a dirty little village in the middle of nowhere. Nothing that happens here is really important.” The town’s lady of easy virtue, Helen Ramirez (Katy Jurado), and Kane’s former paramour, plans to leave on the train when it arrives. She, too, is “acquainted with” Miller. Even Kane’s wife, Amy, will be on that train, refusing to wait around to see if she is to be a widow.

It seems that some people aren’t going to hang around to find out. The judge (Otto Kruger) who sentenced Miller packs his judicial necessities in his saddlebags and rides away, suggesting Kane do the same: “This is just a dirty little village in the middle of nowhere. Nothing that happens here is really important.” The town’s lady of easy virtue, Helen Ramirez (Katy Jurado), and Kane’s former paramour, plans to leave on the train when it arrives. She, too, is “acquainted with” Miller. Even Kane’s wife, Amy, will be on that train, refusing to wait around to see if she is to be a widow.

Kane’s replacement as marshal, Harvey Pell (Lloyd Bridges), turns in his badge under the guise of an argument, though it is apparent he is a coward. As Helen tells her current lover, “You’re a good-looking boy, Harvey. You’ve big, broad shoulders. But [Kane]’s a man. And it takes more than big, broad shoulders to make a man.” Sam Fuller (Harry Morgan) instructs his wife to tell Kane, when he knocks on the door, that he isn’t home.

When Kane goes to the local bar—everyone isn’t in church!—he is met with a fist fight, then cold silence. Likewise, the church service he interrupts earns him the collective argument that it’s not the citizens’ responsibility to back him. Former sheriff, Martin Howe (Lon Chaney, Jr.), suggests people “just don’t care,” refusing to help as well. Although another deputy (Harry Shannon) intends to help when Kane has recruited his deputies, he, too, reneges when he discovers there are no deputies—not a one.

In one high overhead camera shot, Kane is shown isolated in an expanse of empty street with the façades of the buildings on either side, like the walls of a great cauldron or inescapable pit, à la Hitchcock: a lone man in a lonely space. Equally lonely are the recurring shots of the stretch of straight track beside the depot, vanishing into the distance, with the top half of the screen filled with that gray, cloudless sky.

In one high overhead camera shot, Kane is shown isolated in an expanse of empty street with the façades of the buildings on either side, like the walls of a great cauldron or inescapable pit, à la Hitchcock: a lone man in a lonely space. Equally lonely are the recurring shots of the stretch of straight track beside the depot, vanishing into the distance, with the top half of the screen filled with that gray, cloudless sky.

Unlike the expected rousing, fully scored main title, the opening music is a guitar-strumming ballad, “Do Not Forsake Me, O, My Darlin’,” sung by Tex Ritter, with only accordion and drums as accompaniment. In fact, Tiomkin’s score, which eliminates violins altogether, is heavily percussive, reinforced by woodwinds, brass and piano, with the remaining strings—cellos, violas and basses—secondary.

Clocks—clocks with Roman numerals, clocks with Arabic numbers, even watches, even a watch repair shop which Kane walks past in his search for help—are a key motif in the film and, interestingly, time on film is a close approximate of real time.

Clocks—clocks with Roman numerals, clocks with Arabic numbers, even watches, even a watch repair shop which Kane walks past in his search for help—are a key motif in the film and, interestingly, time on film is a close approximate of real time.

Views of clocks, in fact, are keyed with Tiomkin’s music. More so perhaps than the coming gunfight itself, a high point of the film—the arrival of noon—is preceded by the dramatic, agitated development of an incessantly repeated phrase, “O to be torn ’twixt love and duty,” from that title song. With a full-screen shot of a clock, the long crescendo begins quietly with a symbolic “ticking” in harp and pizzicato strings. While the music builds, the screen is filled with alternate shots of nervous townspeople and various clocks until, finally, as the two clock hands reach twelve, the final say is not in the orchestra but a blast of the train whistle.

As in The Fountainhead (Patricia Neal), Garden of Evil (Susan Hayward), Love in the Afternoon (Audrey Hepburn) and Ten North Frederick (Suzy Parker), Cooper in High Noon is playing opposite an actress considerably younger than himself. The film was only Grace Kelly’s second feature movie, after Fourteen Hours the year before.

As in The Fountainhead (Patricia Neal), Garden of Evil (Susan Hayward), Love in the Afternoon (Audrey Hepburn) and Ten North Frederick (Suzy Parker), Cooper in High Noon is playing opposite an actress considerably younger than himself. The film was only Grace Kelly’s second feature movie, after Fourteen Hours the year before.

Her performance in High Noon isn’t anything special, her beauty, for one thing, hidden in a Quaker dress and bonnet. There is little chemistry between the two stars—or enough time or scenes to create any. Alfred Hitchcock was inspired to cast her in Dial M for Murder, the first of their three films, not by seeing either of her earlier films, but from a New York screen test and a viewing of John Ford’s forthcoming Mogambo.

Seems like it was Raoul Walsh—I’ve been unable to verify it—who said that High Noon was a silly movie. Here was this guy running around trying to find deputies to face some gunfighters and defend a town that didn’t want to help—and, after all the search, when he still found himself alone, he stayed, risked his life, killed the baddies, then left town. Or maybe Walsh, or whoever, felt the movie “silly” because it seemed unrealistic that no one, in a town of possibly six hundred, would be honorable enough to render assistance. Wouldn’t the law of averages suggest that someone would have stepped forward?

No matter. High Noon is a great film. There is Cooper to carry it (and, really, he does); if not Cooper, then Tiomkin’s score vitalizes it; if not Tiomkin, then Zinnemann’s direction and Crosby’s camera. Altogether, they couldn’t fail—and didn’t. The movie never grows old. There is nothing to date it. Even all those later “realistic” Westerns which would become much starker and more violent—The Wild Bunch, Unforgiven, Tombstone, The Quick and the Dead—seem pale alongside the directness, the succinctness, of High Noon.

No matter. High Noon is a great film. There is Cooper to carry it (and, really, he does); if not Cooper, then Tiomkin’s score vitalizes it; if not Tiomkin, then Zinnemann’s direction and Crosby’s camera. Altogether, they couldn’t fail—and didn’t. The movie never grows old. There is nothing to date it. Even all those later “realistic” Westerns which would become much starker and more violent—The Wild Bunch, Unforgiven, Tombstone, The Quick and the Dead—seem pale alongside the directness, the succinctness, of High Noon.