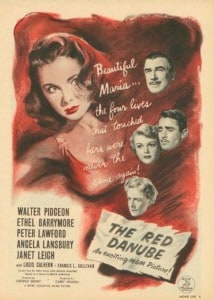

Beautiful Maria…the four lives that touched hers were never the same again!

In the interest of full disclosure, I have to start by stating that I haven’t read and am not familiar with the novel Vespers in Vienna by Bruce Marshall on which today’s film, 1949’s The Red Danube is based. And though some would compare it to the similar The Third Man, The Red Danube has more than enough to stand on its own merit.

Like many pictures of the period, it has a rather cobbled together cast. Unlike most though, here the acting in almost universally excellent. Let’s start at the top. The scene is post World War Two Vienna, with contingents of both British and Russian troops playing large parts in the proceedings.

Walter Pidgeon is British Colonel Hooky Nicobar. An non-believer, Nicobar lost an arm in the First War and his son in the Second. Most of the story centers around Nicobar, who enters the film as a almost rigidly bound career soldier, beholden to carry out orders. Although apparently of questionable faith in accordance with any set Doctrine, Nicobar’s indifference grew after his son was shot down over Germany, just prior to leaving the service for a life in the Church. In accordance, he begins returning Soviet refugees to the Soviets for eventual return to Mother Russia. Not even the suicide of one would-be returned citizen when presented with the news sways him. His colleague Twingo is ill at the mere thought of continuing the round-up of presumed ‘expatriates.’ (Know that expatriates here is a weak cover for political dissidents.)

Rather, it is only the involvement of a young Austrian girl, Maria Buhlen (Janet Leigh) that gets Nicobar’s head thinking. Initially to Nicobar she is just another name on a list and it is only when it becomes clear that another soldier, Twingo (Peter Lawford) has developed a sort of relationship with her that things begin to change. The change in Twingo’s resulting attitude towards Nicobar pushes him to begin questioning much of his own dogma.

Rather, it is only the involvement of a young Austrian girl, Maria Buhlen (Janet Leigh) that gets Nicobar’s head thinking. Initially to Nicobar she is just another name on a list and it is only when it becomes clear that another soldier, Twingo (Peter Lawford) has developed a sort of relationship with her that things begin to change. The change in Twingo’s resulting attitude towards Nicobar pushes him to begin questioning much of his own dogma.

This begins by questioning the policy of cooperation with the Soviets but wanders in short order to Nicobar’s faith. Isolated from Twingo over the fallout from Maria’s departure, he turns to the Reverend Mother (Barrymore), who comes across as a kind-hearted but crafty delight of a character. She first prods Nicobar for responses, but then sits back and observes once she see he is making progress.

Though we don’t alight on Pidgeon often for whatever reason, the performance he gives here is truly surely among his best. At the beginning of the picture you feel his intransigence and the strength of his convictions. Later, you see the tortured conflict the events are causing him. As the conflict builds inside of him and he nears a decision on how to proceed, not only does the language strengthen in verbiage, but more importantly the tone becomes no longer clipped and brusque, but forceful and empowered with knowledge of the proper path.

Though we don’t alight on Pidgeon often for whatever reason, the performance he gives here is truly surely among his best. At the beginning of the picture you feel his intransigence and the strength of his convictions. Later, you see the tortured conflict the events are causing him. As the conflict builds inside of him and he nears a decision on how to proceed, not only does the language strengthen in verbiage, but more importantly the tone becomes no longer clipped and brusque, but forceful and empowered with knowledge of the proper path.

Ethel Barrymore is Mother Auxilia and leads a convent in the area. She becomes over the course of the film the voice of Nicobar’s conscience and evidently has some pull with the Vatican, as she can get in to see the Holy See at the drop of a hat. In conjunction with a surprisingly effective performance by Pidgeon, she is the highlight of the film.

Pidgeon and Barrymore do most of the heavy lifting, but they are provided more than ample support from Peter Lawford (as Major Twingo McPhimister), Angela Lansbury (as Nicobar’s assistant Audrey Quail), and Janet Leigh (as Olga / Maria Buhlen). Leigh and Lansbury aren’t given much of substance to do, but even at fairly early stages in their careers, you can easily see the promise that both had. Leigh has less screen time than Dame Lansbury, yet does more with it. No doubt this is due to her much more pivotal role in the script. It isn’t until the last final twist that Lansbury snaps out of a rather (and I think intentionally so) mousy characterization with a ribald flourish. Lastly, we have Louis Calvern as Colonel Piniev, the resident Vienna and presumed Soviet bad guy.

Pidgeon and Barrymore do most of the heavy lifting, but they are provided more than ample support from Peter Lawford (as Major Twingo McPhimister), Angela Lansbury (as Nicobar’s assistant Audrey Quail), and Janet Leigh (as Olga / Maria Buhlen). Leigh and Lansbury aren’t given much of substance to do, but even at fairly early stages in their careers, you can easily see the promise that both had. Leigh has less screen time than Dame Lansbury, yet does more with it. No doubt this is due to her much more pivotal role in the script. It isn’t until the last final twist that Lansbury snaps out of a rather (and I think intentionally so) mousy characterization with a ribald flourish. Lastly, we have Louis Calvern as Colonel Piniev, the resident Vienna and presumed Soviet bad guy.

Lawford, a personal favorite of mine simply due to his membership in the Rat Pack, even comes off fairly well in the process. Having never (and rightfully so) never becoming a leading man, Lawford does well with the material he is given and provides a stolid, quiet, yet powerful contrast to Pidgeon’s at times slow progress on the path to moral redemption. Lawford- well, let’s say Twingo anyway, long ago reached the end of his own journey down the same path.

Calvern comes off as the heavy, but my take is a bit different. He is really the mirror image of Nicobar- just without the progression. Piniev is still unquestionably serving his superiors, but for this viewer’s perspective scores considerable points when, towards the finale of the film he states to Nicobar succinctly that the two of them are not so different. Even the Christian West, according to Piniev, fights for misguided ideals. He does cite one key difference: honesty. I’m paraphrasing, but the gist is, “You fight for oil, so do we [the Russians]. The difference is we come out and say ‘We fight for oil,’ while you do not.”

Calvern comes off as the heavy, but my take is a bit different. He is really the mirror image of Nicobar- just without the progression. Piniev is still unquestionably serving his superiors, but for this viewer’s perspective scores considerable points when, towards the finale of the film he states to Nicobar succinctly that the two of them are not so different. Even the Christian West, according to Piniev, fights for misguided ideals. He does cite one key difference: honesty. I’m paraphrasing, but the gist is, “You fight for oil, so do we [the Russians]. The difference is we come out and say ‘We fight for oil,’ while you do not.”

One of my few criticisms of the film is, sadly, the score from Miklos Rozsa. For the most part I found it absent, but when it was in the mix it seemed overpowering and attempting to steal the show. Surely the heavy handed main theme, which is most of what you hear, was meant to represent the overbearing yoke of the Soviets and its impact on dissidents and expatriates- or anyone who stood in their way, for that matter. For this rather naïve ear it comes off as just shy of “The March of the Charioteers” from Ben-Hur. The intermittent introduction of the childhood round “Row Your Boat,” gives a nice childlike innocence in the face of such desolation: Physical in the case of their surroundings of war torn Austria, but emotional wreckage plays a very close second.

Yes, many would say this is a story of the Cold War, which even by 1949 had created a frosty crust on relations between the two superpowers. The truth is a bit more sublime than that. Yes, the antagonism between the two nations is depicted and surely with at least some propaganda intent. Yes too, there is the extremely pro-Vatican bent of the picture which speaks further to the West. But at its core, The Red Danube is about nothing more prosaic than a tale of simply making the challenging decisions- which we are all presented with – to do the right thing.

Yes, many would say this is a story of the Cold War, which even by 1949 had created a frosty crust on relations between the two superpowers. The truth is a bit more sublime than that. Yes, the antagonism between the two nations is depicted and surely with at least some propaganda intent. Yes too, there is the extremely pro-Vatican bent of the picture which speaks further to the West. But at its core, The Red Danube is about nothing more prosaic than a tale of simply making the challenging decisions- which we are all presented with – to do the right thing.