“Let me do the talking, angel. I don’t know yet what I’m going to tell them. It’ll be pretty close to the truth.”-Philip Marlowe

Seven bodies! At least that’s the rumored total in Raymond Chandler’s novel The Big Sleep. When William Faulkner and Leigh Brackett were working on the film’s screenplay and couldn’t discern who had murdered one character, they called the author. Chandler told them his identity was in the book, to read it. After checking his own novel, Chandler called back sometime later and told the writers that he didn’t know, that they could designate the killer as they liked.

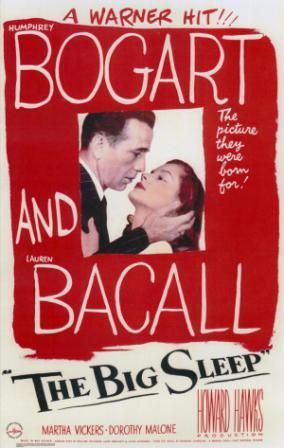

The two screenwriters, even with the talents of a third, Jules Furthman, remained confused by the already confusing first novel of Chandler, and generally retained that murkiness, which might be one of the film’s charms. The Big Sleep is the best of the few detective films Warner Bros. made after The Maltese Falcon during the 1940s. If not plot, then, the big pluses include the tight direction of Howard Hawks, the sharp-edged dialogue—there’s a lot of talking—and the romantic repartee between its two stars, Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall.

Despite Bacall’s come-hither, deep-voiced overtures to her leading man, anyone who has seen the first scene will be astounded by the schoolgirl teasings, no less provocative, of Martha Vickers as a precocious nymph, Bacall’s sister in the film, and wonder why she’s not seen more.

Despite Bacall’s come-hither, deep-voiced overtures to her leading man, anyone who has seen the first scene will be astounded by the schoolgirl teasings, no less provocative, of Martha Vickers as a precocious nymph, Bacall’s sister in the film, and wonder why she’s not seen more.

In fact, Vickers’ sexy chemistry was so threatening to the studio’s new discovery—this only Bacall’s fourth film after her sensational début in To Have and Have Not (1944)—that most of the younger (by about eight months) star’s scenes were cut. A major overhaul of Bacall’s part by the studio and director ensued, with reshoots, new scenes and added sexual innuendos between her and Bogart.

Filming was further complicated by the tension of Bogart’s impending divorce from his third wife and the affair he was conducting on the set with Bacall. Rumor had it that Bacall was so nervous over the divorce, and, from some sources, that the actor was still debating whether to proceed with the divorce, that during filming her hands shook when she poured a drink or lighted a cigarette.

Bacall had written in her autobiography, By Myself, that, despite the anxiety over the divorce, much fun was had on the set, which prompted a cautionary memo from studio head Jack L. Warner. And when the most famous of the screenwriters, William Faulkner, author of The Sound and the Fury and other stories of the South, asked Hawks if he could write “from home,” since the studio atmosphere unnerved him, Hawks okayed the request, assuming the writer meant his office at the studio. The director was quite displeased when he learned that Faulkner was writing from“home” all right—in Oxford, Mississippi.

Bacall had written in her autobiography, By Myself, that, despite the anxiety over the divorce, much fun was had on the set, which prompted a cautionary memo from studio head Jack L. Warner. And when the most famous of the screenwriters, William Faulkner, author of The Sound and the Fury and other stories of the South, asked Hawks if he could write “from home,” since the studio atmosphere unnerved him, Hawks okayed the request, assuming the writer meant his office at the studio. The director was quite displeased when he learned that Faulkner was writing from“home” all right—in Oxford, Mississippi.

Some brave souls have tried to condense the impenetrable plot into a nutshell, though, at best, it’s of minimum importance. Let’s see, how does it go, or appears to go. . . .

Private detective Philip Marlowe (Bogart) visits a decaying old man, General Sternwood (Charles Waldron, who died before the film was released), who sits, wheelchair-bound, shawl-enshrouded, in his putrefying greenhouse. (In the 1978 remake, James Stewart’s portrayal of the role seems more a copy of Waldron’s performance than any original approach of his own.) The dialogue in this one scene, and coming so early in the film, can be seen as setting the ethical tone of the movie and the nature of the characters, the private eye included.

The General says to Marlowe:

“You may smoke, too. I can still enjoy the smell of it. Hum, nice state of affairs when a man has to indulge his vices by proxy. You’re looking, sir, at a very dull survival of a very gaudy life—crippled, paralyzed in both legs, barely I eat and my sleep is so near waking it’s hardly worth the name. I seem to exist largely on heat, like a newborn spider.”

He tells Marlowe that he’s being blackmailed, again, and asks him to check on the gambling debts his younger daughter, Carmen (Vickers), owes to a book dealer named Geiger (Theodore von Eltz). (Carmen is a nymphomaniac in Chandler’s novel, but the Hollywood censors would permit no more than what is seen; any inferences otherwise must be the viewer’s own.)

As Marlowe is leaving, the butler (Charles D. Brown) tells him Mrs. Vivian Rutledge (Bacall) would like to see him. In trying to feel him out, she confides that she believes her father has asked him to search for his friend Sean Regan, who has been missing for a month.

As Marlowe is leaving, the butler (Charles D. Brown) tells him Mrs. Vivian Rutledge (Bacall) would like to see him. In trying to feel him out, she confides that she believes her father has asked him to search for his friend Sean Regan, who has been missing for a month.

Next scene, Marlowe visits Geiger’s rare bookstore (a source for pornography in Chandler’s novel). With the front of his hat turned up, he assumes a clipped speech and eccentric manner, asking for specific editions of two books. The proprietor (Sonia Darrin) says she doesn’t have them.

He then goes across the street to another book store run by a proprietress (Dorothy Malone) who comes on to Marlowe, and he to her. He asks her for the same editions of the books and she rightly tells him there are none. “The girl in Geiger’s bookstore,” he says, “didn’t know that.”

He asks her if she knows Geiger on sight, she describes him down to his glass eye and he requests she let him know when he comes out of the bookstore. (The three-and-a-half-minute scene is one of the best in the film, and, interesting, like Marlowe’s scene with Sternwood, it exudes rapport and chemistry without Bacall.)

When Geiger does emerge, Marlowe follows him to a house. Hearing a woman’s scream and a gunshot, he enters to find a dead Geiger, a drugged Carmen and a hidden camera, without any film. After taking Carmen home, he returns to the house, only to find . . . the body is gone.

When Geiger does emerge, Marlowe follows him to a house. Hearing a woman’s scream and a gunshot, he enters to find a dead Geiger, a drugged Carmen and a hidden camera, without any film. After taking Carmen home, he returns to the house, only to find . . . the body is gone.

It’s just the beginning, and from here on it’s nothing but a convoluted, indecipherable mess, first and most prominent, murder, then gambling, blackmail, car chases (not the apoplectic ones of today), love triangles, red herrings, organized crime, subtle suggestions of pornography and general mayhem.

Although no threat to the overwhelming charisma between Bogart and Bacall, the dialogue has its own fascination, often poetic and occasionally unforgettable, however “written” it may sometimes sound. This is true of General Sternwood’s lines in his one scene and in some of Marlowe’s, particularly this retort during his first scene with Vivian, when she says she deplores his manners:

“And I’m not crazy about yours. I didn’t ask to see you. I don’t mind if you don’t like my manners. I don’t like them myself. They are pretty bad. I grieve over them on long, winter evenings. I don’t mind you ritzing me or drinking your lunch out of a bottle, but don’t waste your time trying to cross-examine me.”

These lines, some given at a fast, breathless pace, are reminiscent of a Bogart scene in The Maltese Falcon—the address to the district attorney about “the only chance I’ve got of catching them [the murderers], and tying them up, and bringing them in, is by staying as far away as possible from you and the police . . . ”

These lines, some given at a fast, breathless pace, are reminiscent of a Bogart scene in The Maltese Falcon—the address to the district attorney about “the only chance I’ve got of catching them [the murderers], and tying them up, and bringing them in, is by staying as far away as possible from you and the police . . . ”

The most famous dialogue exchange, with its sexual innuendos, is between Bogart and Bacall, sitting across from each other at a nightclub table:

“Speaking of horses,” she says, “I like to play them myself. But I like to see them work out a little first, see if they’re front runners or come from behind, find out what their hole card is, what makes them run. . . . I’d say you don’t like to be rated. You like to get out in front, open up a little lead, take a little breather in the backstretch and then come home free.”

“You don’t like to be rated yourself,” he says.

“I haven’t met any one yet who can do it. Any suggestions?”

“Well, I can’t tell till I’ve seen you over a distance of ground. You’ve got a touch of class, but I don’t know how far you can go.”

“A lot depends on who’s in the saddle.”

This scene doesn’t need, and doesn’t receive, any underpinning music. Max Steiner’s musical score is one of his more problematic, containing both the strong and weak points of his style. The main title is something of a nondescript blur, noisy and tuneless, serving, if nothing else, as a foretaste of the impervious plot and unsavory characters.

In the insouciant motif for Philip Marlowe, Steiner captures the detective’s sluggish, yet quixotic nature, which serves to brighten the predominantly dark music. The slowly ascending notes at the start of the main love theme suggest, perhaps—assuming Steiner’s thinking was this nuanced—the hostile beginning of Marlowe and Vivian’s relationship, the rest of the theme infused with a kind of smothered passion their love would become by the end.

In the insouciant motif for Philip Marlowe, Steiner captures the detective’s sluggish, yet quixotic nature, which serves to brighten the predominantly dark music. The slowly ascending notes at the start of the main love theme suggest, perhaps—assuming Steiner’s thinking was this nuanced—the hostile beginning of Marlowe and Vivian’s relationship, the rest of the theme infused with a kind of smothered passion their love would become by the end.

In scoring for two similar settings, it is interesting to compare the disparate approaches to the greenhouse scene, with all its tropical trees and ferns, and Violet Venable’s (Katharine Hepburn) jungle garden in Suddenly, Last Summer (1959). For whatever the reason, Steiner elects to ignore representing the humid atmosphere General Sternwood has prepared for his orchids, while composers Malcolm Arnold and Buxton Orr convey almost breathable damp and mildew for Violet’s steamy surroundings.

The Big Sleep is a film where everyone except General Sternwood—perhaps he, too, if he had another scene—carries a gun, and when guns are unavailable, then fists do quite well. With the moral slant of the film, that is, with less than admirable characters and their ugly motives, it’s hard to like any of them.

Truth is, you’re not supposed to like the characters in a film noir, sympathize with them maybe.. But the actors you can like. It’s hard not to like Bogart and Bacall—not as accomplished actors, but as personalities of the screen, as stars were viewed in the ’30s and ’40. Then movie-goers didn’t go to see Philip Marlowe or Vivian Rutledge, not that any one coming out of the theater would remember her last name; they went to see Bogart and Bacall.

Truth is, you’re not supposed to like the characters in a film noir, sympathize with them maybe.. But the actors you can like. It’s hard not to like Bogart and Bacall—not as accomplished actors, but as personalities of the screen, as stars were viewed in the ’30s and ’40. Then movie-goers didn’t go to see Philip Marlowe or Vivian Rutledge, not that any one coming out of the theater would remember her last name; they went to see Bogart and Bacall.

Bogart, like Cagney and Flynn, is a personality, a man who always, or generally always, plays himself. Bacall, who still hadn’t learned to act at the time of The Big Sleep, would have been easily overshadowed by Vickers had her original scenes been left intact, and Dorothy Malone has all the charisma and magic of Bacall, just another kind of charm.

Bosley Crowther, one of the most famous movie critics of the 1940s, warned in his New York Times review of August 24, 1946, that the film would be confusing and unsatisfying. And apparently in all sincerity, he asked, “[W]ould somebody also tell us the meaning of that title . . . ” Why, it’s what seems obvious, that which at least seven of the characters in The Big Sleep experienced . . . DEATH.