“Hitler is a monster of wickedness, insatiable in his lust for blood and plunder. . . .So now this bloodthirsty guttersnipe must launch his mechanized armies upon new fields of slaughter, pillage and devastation.”—from Winston Churchill’s radio broadcast upon the German invasion of Russia, June 22, 1941

My love of history, especially the American Civil War, World War II and British history, was excited some years ago in viewing Oliver Hirschbiegel’s Downfall, about the last days of Adolf Hitler in the bunker. The residual glow from this experience, combined with a recent rereading of Albert Speer’s Inside the Third Reich, has inspired this examination of Downfall and two other movies about what happened in that claustrophobic underground den in the early months of 1945.

Current fiction rarely interests me. Biographies, on the other hand, are perhaps my number one reading, and Speer’s autobiography, written during and after his twenty years in Spandau prison, is also a multi-biography of the “gangsters,” as Winston Churchill called them, who surrounded Hitler. Speer, not quite in the “gangster” category, was Hitler’s architect and later Minister of Armaments and Munitions.

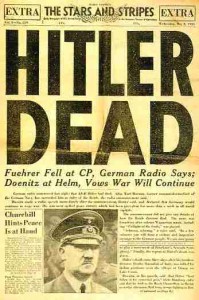

Evil  men, for me, are a definite turn-off—except, strangely, in the case of Hitler. I’m curious about him, fascinated in fact by how such a mind worked and what made the man what he was—the hatred, the bigotry, the indifference toward people, loved ones as well as the man in the street; above all, what made him so evil. They—“they”: those who study such things—proclaim that Stalin killed more people than old Adolf ever thought of killing. That might be true as regards their individual “killing specialties”—for Stalin the Russian peasants and the army elite, for Hitler the Jews and other “sub humans”—but surely the “honor” must clearly go to Hitler, for, after all, he started WWII, and how many souls, combatants and civilians, died between 1939 and 1945 . . . sixty million, was it?

men, for me, are a definite turn-off—except, strangely, in the case of Hitler. I’m curious about him, fascinated in fact by how such a mind worked and what made the man what he was—the hatred, the bigotry, the indifference toward people, loved ones as well as the man in the street; above all, what made him so evil. They—“they”: those who study such things—proclaim that Stalin killed more people than old Adolf ever thought of killing. That might be true as regards their individual “killing specialties”—for Stalin the Russian peasants and the army elite, for Hitler the Jews and other “sub humans”—but surely the “honor” must clearly go to Hitler, for, after all, he started WWII, and how many souls, combatants and civilians, died between 1939 and 1945 . . . sixty million, was it?

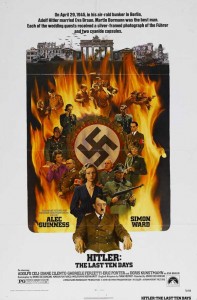

For these musings, three film versions of Hitler’s last days come to mind—there’re others—which are successful to varying degrees. In the oldest, Hitler: The Last Ten Days (1973), Alec Guinness is the best of the three actors in recreating the dilettante philosopher and teller of tales, epitomized in the trivial monologues that exasperated his dining and late evening cohorts, monologues about his early struggle for power, how he could have been a great architect were it not for his political obligations, plans for his elaborate tomb in Linz, the advantages of a vegetarian diet and, believe it or not, the difficulties of recognizing a madman! (He could, of course, have looked in the mirror but would have seen his own egomania reflected back: the military genius and the great unifier of the German-speaking peoples, guided by Providence. He never hesitated to call himself a “great man.”)

For these musings, three film versions of Hitler’s last days come to mind—there’re others—which are successful to varying degrees. In the oldest, Hitler: The Last Ten Days (1973), Alec Guinness is the best of the three actors in recreating the dilettante philosopher and teller of tales, epitomized in the trivial monologues that exasperated his dining and late evening cohorts, monologues about his early struggle for power, how he could have been a great architect were it not for his political obligations, plans for his elaborate tomb in Linz, the advantages of a vegetarian diet and, believe it or not, the difficulties of recognizing a madman! (He could, of course, have looked in the mirror but would have seen his own egomania reflected back: the military genius and the great unifier of the German-speaking peoples, guided by Providence. He never hesitated to call himself a “great man.”)

Guinness’ nonchalance in passing out cyanide pills at Hitler’s final birthday party is chilling. “It’s not the present I was hoping to give you, my dear Magda,” he says casually to Joseph Goebbels’ wife.

The British-Italian production, with Gabriele Ferzetti as Field Marshall Keitel and Adolfo Celi as General Krebs, is hampered by a weak script. There is almost too much emphasis on those monologues, though Guinness does them well, so well that the viewer may experience some of the fatigue the original listeners felt. As further recommendation for Speer’s book—I can’t recommend it too highly—these impromptu speeches are vividly related in Inside the Third Reich.

The British-Italian production, with Gabriele Ferzetti as Field Marshall Keitel and Adolfo Celi as General Krebs, is hampered by a weak script. There is almost too much emphasis on those monologues, though Guinness does them well, so well that the viewer may experience some of the fatigue the original listeners felt. As further recommendation for Speer’s book—I can’t recommend it too highly—these impromptu speeches are vividly related in Inside the Third Reich.

Simon Ward, who had the title role in Young Winston the year before, is somewhat “misplaced” at various times as a visiting Captain Hoffman. General Burgdorf, himself indistinguishable from the officers who endured Hitler’s daily situation conferences and given only a few lines, is Joss Ackland; I remember him as the Russian ambassador in The Hunt for Red October. Albert Speer, who writes of being at Hitler’s final birthday party, is never seen in the film.

A conundrum which plagues all of these movies is how far to go in presenting words and scenes which are unrecorded, and have no witnesses. As, for example, the deaths of Hitler and Eva Braun. The two had retired to Hitler’s sitting room, and it’s pure conjecture as to what was said and who died first, if not simultaneously.

In Hitler: The Last Ten Days Ennio De Concini and his co-writers concoct a tirade (another one!) from Hitler, declaring Eva’s serious mental shortcomings as a woman, that she has no significance. “You lived close to me—isn’t that enough for you?” he shouts. Despondent over this, if there is room for any further despondence at the moment of one’s suicide!, she takes a cyanide pill while Hitler’s back is turned.

In Hitler: The Last Ten Days Ennio De Concini and his co-writers concoct a tirade (another one!) from Hitler, declaring Eva’s serious mental shortcomings as a woman, that she has no significance. “You lived close to me—isn’t that enough for you?” he shouts. Despondent over this, if there is room for any further despondence at the moment of one’s suicide!, she takes a cyanide pill while Hitler’s back is turned.

I like the European map graphics behind the opening credits, showing first the spread of the Führer’s empire, then its shrinking, all engulfed in symbolic flames, until Hitler’s dominion is restricted to a few blocks in destroyed Berlin—all backed by Wagner’s Act III Prelude to Lohengrin. There is other Wagnerian music during the film, “Siegfried’s Funeral Music” from Götterdämmerung, darkly appropriate, and waltzes from Johann Strauss, Jr.’s Die Fledermaus, comically bizarre in the surrounding chaos.

(Speer relates in his book how he had the lights turned on for the final concert of the Berlin Philharmonic, April 12, 1945. “When Bruckner’s ‘Romantic’ Symphony is played,” he told friends, “it will mean the end is upon us.” It seemed part of the German psyche to have pride, even in defeat, and to make the collapse of a nation a grand occasion. Speer ordered the Beethoven Violin Concerto and Brünnhilde’s last air from Götterdämmerung, because wasn’t it, after all, the twilight of the gods? For the Nazis had never been so humble as to regard themselves as anything less than gods; for the life and death they held over so many millions of people, they must have been gods!)

Hitler: The Last Ten Days ends with a last laugh on old Adolf. Earlier, it had been established that he forbade smoking in his presence—he even boasted of how this dictum helped him politically—but after his death, those in the bunker begin smoking, and, accompanied by the noise of Russian guns and exploding shells from above, the film closes with Die Fledermaus.

Anthony Hopkins, who has portrayed Nixon, C. S. Lewis, Captain Bligh, Picasso, John Quincy Adams and David Lloyd George, among other historic figures, came inevitably, one would almost believe, to the role of Adolf Hitler in the TV movie The Bunker (1981). Hopkins seems the angriest of the three actors, his face sometimes turning red, if from the benefit of lighting it is hard to know. As Speer relates in Inside the Third Reich, the anger, obstinacy and defiance became more dominate as the end neared.

Anthony Hopkins, who has portrayed Nixon, C. S. Lewis, Captain Bligh, Picasso, John Quincy Adams and David Lloyd George, among other historic figures, came inevitably, one would almost believe, to the role of Adolf Hitler in the TV movie The Bunker (1981). Hopkins seems the angriest of the three actors, his face sometimes turning red, if from the benefit of lighting it is hard to know. As Speer relates in Inside the Third Reich, the anger, obstinacy and defiance became more dominate as the end neared.

Richard Jordan’s performance as Albert Speer is perhaps just a little too subdued, though he more than adequately conveys Speer’s intelligence. This version of the last days in the Führerbunker is the only one of these three films which relates, from Speer’s book, the architect’s scheme to kill Hitler. With the help of Dieter Stahl (Edward Hardwicke), Speer plans to conduct poisonous gas through the ventilation system via the outside ground level vent. Before the plan can be attempted, however, the vent is inexplicably remodeled as a ten-foot chimney. In the book, Speer writes, “My first thought was that my plan had been discovered. But actually the whole thing was the operation of chance.”