When the frogs stop croaking . . . watch out!

The beginning of Night Monster is rather subdued but with enough hints of disquiet and mystery to stimulate the interest. In keeping with the body-plentiful tradition of Universal horror films of the ’30s and ’40s, there will be eight deaths, including one which has occurred before the movie begins. Distracting from this, however, is the talky script, which has a positive effect, extending the suspense between body-findings.

At the fog-enshrouded Ingston mansion, the gate keeper (Cyril Delevanti, Deborah Kerr’s grandfather in The Night of the Iguana, 1964) opens the gate for a man who apparently has walked down the dirt road from nowhere. Inside the house, he sees the housekeeper, Sarah Judd (Doris Lloyd, the Baroness Ebberfeld in The Sound of Music, 1956), on her knees, scrubbing a spot on the carpeted steps of an elaborate staircase.

The man, who wears a turban, watches from behind a balustrade as Margaret Ingston (Fay Helm, Mrs. Fuddle in the Blondie series, 1938-50), daughter of the household head, approaches Judd and accuses her of cleaning blood from the carpet. The two argue, Margaret insisting she isn’t insane and the housekeeper finally sending her to her room—a servant giving orders to her employer?

Later, the maid, Milly Carson (Janet Shaw, the waitress at the Till Two bar in Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt, 1943), descends the staircase and phones the local constable. Her warnings about the strange goings-on in the Ingston household are cut short by the butler, Rolf (Bela Lugosi), who quietly emerges through the door behind her. She gives her notice and prepares to leave.

Later, the maid, Milly Carson (Janet Shaw, the waitress at the Till Two bar in Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt, 1943), descends the staircase and phones the local constable. Her warnings about the strange goings-on in the Ingston household are cut short by the butler, Rolf (Bela Lugosi), who quietly emerges through the door behind her. She gives her notice and prepares to leave.

With this atmosphere—the sense of unrest, the suspicious characters and the underlying creepy music—the mood is set. . . .

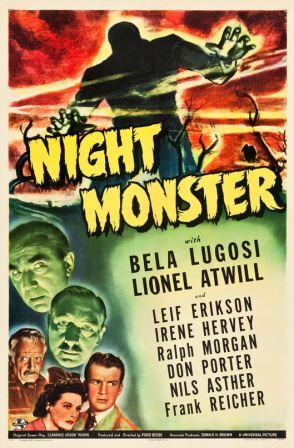

Despite the bodies that will accumulate, the two top-billed stars in Night Monster step outside their usual sinister roles, their names used here for their marquee value. Lugosi, well into a physical and mental collapse, is relegated to the role of butler, either announcing dinner, summoning guests to the library or finding bodies. The Human Monster, back in 1940, is the last film to qualify as a true Lugosi vehicle.

Lionel Atwill, though much more of a star than his two doctor companions, is the first of the three to be dispatched, after only a brief time on screen. 1942 was one of his busiest years, playing doctors in both The Mad Doctor of Market Street and The Ghost of Frankenstein, and important roles in To Be or Not to Be and Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon as Moriarity opposite Basil Rathbone’s Holmes. He appeared in nine films that year.

Lionel Atwill, though much more of a star than his two doctor companions, is the first of the three to be dispatched, after only a brief time on screen. 1942 was one of his busiest years, playing doctors in both The Mad Doctor of Market Street and The Ghost of Frankenstein, and important roles in To Be or Not to Be and Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon as Moriarity opposite Basil Rathbone’s Holmes. He appeared in nine films that year.

Directed by Ford Beebe, Night Monster comes at a time when the luster of Universal as the master of horror is clearly in decline. The abundant fog around the Ingston mansion, and on the much-traveled road leading to it, is essential to hide a barren set. The elaborate two-level staircase appears in many of the studio’s films.

Much of the spirit and many of the trademarks of Universal, however, still shine through. Hans J. Salter’s music, one of the strongest ingredients in the film, provides an eerie atmosphere, starting with the main title, which would be reused in The Ghost of Frankenstein. Behind the opening credits, as so often in the studio’s horror movies, the camera traverses those familiar, desolate, foggy woods, as in The Wolf Man (1941).

Charles Van Enger, rather undistinguished as cinematographers go, was nonetheless a stalwart of Universal and Warner Bros. His greatest claim to fame is his uncredited work on the 1925 Lon Chaney, Sr. Phantom of the Opera. He spent the last years of his career in television—Lassie, The Betty Hutton Show, Gilligan’s Island and many others.

Charles Van Enger, rather undistinguished as cinematographers go, was nonetheless a stalwart of Universal and Warner Bros. His greatest claim to fame is his uncredited work on the 1925 Lon Chaney, Sr. Phantom of the Opera. He spent the last years of his career in television—Lassie, The Betty Hutton Show, Gilligan’s Island and many others.

Returning to the doings at the mansion, Laurie, the lecherous chauffeur (Leif Erickson, best known for TV’s The High Chaparral, 1967-71), has been sent by the head of the household, Kurt Ingston (Ralph Morgan, brother of Frank, Professor Marvel in The Wizard of Oz, 1939), to the train station to pick up three doctors.

Doctors King (Atwill), Timmons (Frank Reicher, the ship captain in King Kong, 1933) and Phipps (Francis Pierlot, player of small roles, such as Herkimer in Anne of the Indies, 1951) had earlier attended the wheelchair-bound Ingston, who, after his “major illness,” as King describes it, is now without arms and legs.

Ingston seems free of grudges, saying the doctors did all that medical science allowed. “I don’t think you’ve ever been properly rewarded,” he tells them at dinner. “But you will be. You will be.”

Summoned by Margaret Ingston, a fourth doctor, psychiatrist Lynn Harper (Irene Hervey, her last movie role was in Clint Eastwood’s Play Misty for Me, 1971), is en route when her car breaks down. Walking down the road toward the mansion, she hears a scream, just after the frogs had stopped croaking, but fortunately meets a car driven by a frequent visitor to the Ingstons, Dick Baldwin (Don Porter, most adept in comic roles in both movies and TV).

Summoned by Margaret Ingston, a fourth doctor, psychiatrist Lynn Harper (Irene Hervey, her last movie role was in Clint Eastwood’s Play Misty for Me, 1971), is en route when her car breaks down. Walking down the road toward the mansion, she hears a scream, just after the frogs had stopped croaking, but fortunately meets a car driven by a frequent visitor to the Ingstons, Dick Baldwin (Don Porter, most adept in comic roles in both movies and TV).

With patches of blood near the body, a strangled Milly—the source of the scream—is found by Constable Cap Beggs (Robert Homans, grim-faced actor of countless judges and law officers). Beggs was alerted by the buggy-driving Jed Harmon (Eddy Waller, character actor in many a Western) of the suspicious whereabouts of the maid.

The eavesdropping man with the turban turns out to be a live-in guest, an Eastern mystic, Agor Singh (Niles Asther, a Danish actor who once proposed, unsuccessfully, to Greta Garbo). In an incomprehensible discourse to guests in the library, Singh explains how rearranging “cosmic substances” can materialize objects through deep concentration.

He demonstrates by evoking a kneeling skeleton—the undoubted work of Universal’s special effects master John P. Fulton, though no screen credit is given. Singh says certain details in the process, such as the residual blood, even after the skeleton itself has disappeared, cannot be explained to the “uninitiated.”

He demonstrates by evoking a kneeling skeleton—the undoubted work of Universal’s special effects master John P. Fulton, though no screen credit is given. Singh says certain details in the process, such as the residual blood, even after the skeleton itself has disappeared, cannot be explained to the “uninitiated.”

During a later scene in the library, Rolf enters to summon everyone to the room of Dr. King—strangled by his bed, only a claw-like hand visible and blood blotches on the floor. Then, between various stretches of dialogue, follows the similar death of Dr. Timmons, a hand clutching the bedspread. After Dr. Phipps has also been strangled, Baldwin and Beggs follow the blood to a secret passage (a set from The Cat and the Canary, 1939).

Margaret argues with housekeeper Judd and sets fire to the house in a fit of insanity while, outside in the woods, Baldwin and Harper are being stalked by a shadowy, stiff-walking man. It’s Kurt Ingston! But he’s . . . walking! (Was there ever any doubt that he was the murderer? A man in a wheelchair should always be the first suspected—and, quite often, he’ll be the killer.)

Failing to kill Baldwin, Ingston tries to strangle Harper, but Singh appears and shoots him, his legs gradually dematerializing as he dies. In the background, flames consume the Ingston mansion—the same model used in The Ghost of Frankenstein.

For what it is, Night Monster isn’t all that bad. Of course it never escapes its class “B” horror status, not that it tries or wants to, but it has a certain measured, suspenseful pace. The key murders, Milly’s aside, are sensitively spaced, beginning later in the plot than perhaps expected. While Calvin Thomas Beck, for example, accords the movie only one line in passing, justified in the context of his Heroes of the Horrors, as it’s not a Lugosi vehicle, a number of other critics give Night Monster surprisingly high marks. A competent cast moves about in sharp black-and-white photography, and the premise of materializing legs to commit murder is a little different.

For what it is, Night Monster isn’t all that bad. Of course it never escapes its class “B” horror status, not that it tries or wants to, but it has a certain measured, suspenseful pace. The key murders, Milly’s aside, are sensitively spaced, beginning later in the plot than perhaps expected. While Calvin Thomas Beck, for example, accords the movie only one line in passing, justified in the context of his Heroes of the Horrors, as it’s not a Lugosi vehicle, a number of other critics give Night Monster surprisingly high marks. A competent cast moves about in sharp black-and-white photography, and the premise of materializing legs to commit murder is a little different.

And what better way to end a horror movie about a ridiculous, untenable premise than with an appropriately empty warning, presumably to those who might try rearranging those cosmic substances: “A little knowledge of the occult is dangerous,” Singh ruminates in the film’s last lines. “Unless it’s used for good, disaster will follow its wake. That is Cosmic Law.”

Let that be a lesson.