“But, Susan, you can’t climb in a man’s bedroom window!” David Huxley says to Susan Vance, and she replies, “I know, it’s on the second floor!”

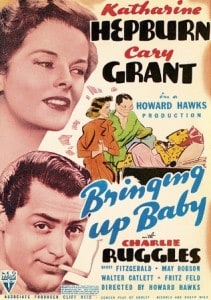

So “far back” in movie history, at least for some members of the younger generation, it seems hard to believe that the comedy in Bringing Up Baby, especially its slapstick aspects, has never been bettered. It was [intlink id=”282″ type=”category”]Katharine Hepburn[/intlink]’s first film in that genre, and she had to be coached on proper timing, though the grace of her movements needed no advice. [intlink id=”269″ type=”category”]Cary Grant[/intlink], her bewildered co-star—at least bewildered most of the time on screen—needed no such coaching, for his timing had been perfect for years, acquired on the British vaudeville stage before he came to Tinseltown.

Hepburn had made one previous film with Grant, Sylvia Scarlett, in 1936, directed by her favorite director, George Cukor, and the trio would make three more films together, Bringing Up Baby, Holiday and The Philadelphia Story. Not that Bringing Up Baby is a Hepburn show. It isn’t. Grant shares equal screen time; in fact, one star is rarely seen without the other, as the nature of the plot deems that they be inseparable. And the chemistry and interplay between them is undeniable—and contagious.

A quiet, bespectacled paleontologist, David Huxley (Grant), is in the process of assembling a brontosaurus skeleton but is missing one bone. Although he is preparing to marry an overly serious-minded colleague, Alice Swallow (Virginia Walker), his bigger problem—he doesn’t see the imminent wedding to Swallow as a “problem” though he should—is to somehow find the money to finance his further work. He must persuade a dowager, Elizabeth Random (May Robson), to donate a million dollar endowment to his museum.

Luckily for him, though it doesn’t seem so at the time, just before the wedding day, he meets heiress Susan Vance (Hepburn). Susan’s wild and flighty ways put him off from the start and for most of their coming adventures together—and that they are, adventures. She interrupts his golf game (Hepburn was an avid golfer), damages his car, drenches him in a stream and any number of other capers.

And then there’s that faux pas in a restaurant. This, the film’s most famous routine, was based on an actual experience of Grant’s. David unknowingly is standing on the hem of Susan’s long evening gown when she walks away, ripping the material at the waist. Unaware, she continues on ahead. He attempts to explain, then tries to cover her exposed underwear with his top hat. It’s only after she feels behind her back that she realizes what he’s tried to tell her. As they make their exit, he walks close-tight behind her, earning laughter from the crowd.

And then there’s that faux pas in a restaurant. This, the film’s most famous routine, was based on an actual experience of Grant’s. David unknowingly is standing on the hem of Susan’s long evening gown when she walks away, ripping the material at the waist. Unaware, she continues on ahead. He attempts to explain, then tries to cover her exposed underwear with his top hat. It’s only after she feels behind her back that she realizes what he’s tried to tell her. As they make their exit, he walks close-tight behind her, earning laughter from the crowd.

All this disorder serves to thwart David’s efforts to impress Alexander Peabody (George Irving), Mrs. Random’s lawyer from whom is required the approve for that million dollars. Susan, unknown to David at first, just happens to be Random’s niece.

To make things more confusing, and the perfect setup for slapstick, Susan has received from her brother a leopard named Baby, an intended gift for their aunt. Susan, thinking David is a zoologist, convinces him to join her at her Connecticut country home, where they can better attend Baby, which is best calmed when hearing “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love.” Speaking of which, Susan quickly falls in love with David and, to prevent his marriage to whatshername, diverts his attention and puts any number of obstacles in his path.

In one of the film’s most hilarious scenes, dressed in Susan’s sheer bathrobe, David meets Random and her old friend Major Applegate (Charles Ruggles). While he was taking a shower, Susan had hidden his clothes. The goings-on here are complete with Grant’s comedic double-takes, mutterings to himself and attempts to get a word in edgeways, mannerisms that will later become so exaggerated and annoying in Arsenic and Old Lace, but here applied in tolerable doses.

In one of the film’s most hilarious scenes, dressed in Susan’s sheer bathrobe, David meets Random and her old friend Major Applegate (Charles Ruggles). While he was taking a shower, Susan had hidden his clothes. The goings-on here are complete with Grant’s comedic double-takes, mutterings to himself and attempts to get a word in edgeways, mannerisms that will later become so exaggerated and annoying in Arsenic and Old Lace, but here applied in tolerable doses.