I didn’t show up at the ceremony to collect any of my first three Oscars. Once I went fishing, another time there was a war on, and on another occasion, I remember, I was suddenly taken drunk. -John Ford

When Orson Welles was asked to identify the best three American directors, his reply was, “John Ford. John Ford, and John Ford.”

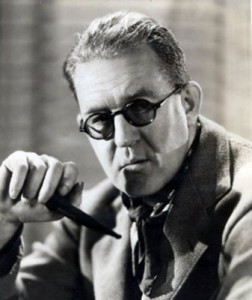

In the pantheon of American Film Directors, no one would list Sean O’Fearna at the top of their list. Most would not have him on their list at all and even a few readers may well question…who in the heck is Sean O’Fearna? Well perhaps you know him better by the name which would undoubtedly appear on all such lists. Sean O’Fearna is better known by his taken name of John Ford, one of the great directors of history and perhaps the quintessential director of the American West.

Ford would follow his more famous brother (at least originally this was true), Francis Ford, west to California and the motion picture business. The rest perhaps is history, and although many of his early pictures are lost, his extant pictures are numerous. It is hard to describe Ford’s films in a few words. Perhaps Patriotic, Visionary, and Powerful. And, as time progressed, somewhat remorseful (note the lower case ‘r’.)

Ford would follow his more famous brother (at least originally this was true), Francis Ford, west to California and the motion picture business. The rest perhaps is history, and although many of his early pictures are lost, his extant pictures are numerous. It is hard to describe Ford’s films in a few words. Perhaps Patriotic, Visionary, and Powerful. And, as time progressed, somewhat remorseful (note the lower case ‘r’.)

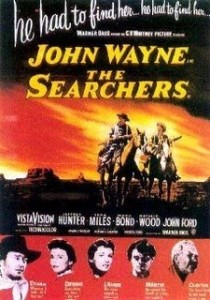

We’ve reviewed a few of Ford’s films before, notably The Prisoner of Shark Island, They Were Expendable, and Cheyenne Autumn, none of which any would place among his best- especially the latter. At some point we’ll get to his penultimate pictures like The Quiet Man, The Searchers, and The Grapes of Wrath.

I recently finished the phenomenal biography of Ford by Scott Eyman entitled Print the Legend: The Life and Times of John Ford. It has been out a while, being first published in 1999, and is no fluff piece. Index and all it clocks in at over 650 pages. But in spite of its seeming bulk it reads like the best dime store novel and is insanely hard to put down.

The book in extremely detailed and we see both Ford’s rise through the silent and early talkie era and eventual decline as he continued to work literally until ill health prevented it. And, as Eyman skillfully points out, this eternal push for work was not the result of any unyielding love of the movies (although such a love Ford undoubtedly had), but a pure and simple need for cash.

And his later work suffered. Although his last feature was 1966’s 7 Women, his last truly good film was The Searchers of ten years prior. In the interim almost everything about the Ford persona came into question. He was more yielding on set, permitting both iced beer and “lip” from actors. His eyes were failing and it became clear to all that he was simply punching a clock. Moments of the classic Ford brilliance of old still flashed through, but Ford was aged beyond his years and frequently overlooked his usual standards for the sake of expediency.

And his later work suffered. Although his last feature was 1966’s 7 Women, his last truly good film was The Searchers of ten years prior. In the interim almost everything about the Ford persona came into question. He was more yielding on set, permitting both iced beer and “lip” from actors. His eyes were failing and it became clear to all that he was simply punching a clock. Moments of the classic Ford brilliance of old still flashed through, but Ford was aged beyond his years and frequently overlooked his usual standards for the sake of expediency.

It is a wonderful book, and everyone should grab a copy. Life most biographies I like, this focuses on the professional side and either doesn’t comment at all or merely hints at the more gossipy side of life. We get a pretty hefty dose of detail on Ford’s drinking, but only hints at potential (and neither are even close to confirmed here) liaisons with Katharine Hepburn and Maureen O’Hara. The focus is always on the pictures, as well it should be.

As I’ve been on a bit of a Ford “kick” of late, I also looked at the 2006 version of Peter Bogdanovich’s documentary Directed by John Ford, a rather (as expected) nostalgic look at the director with commentary from many of his colleagues and successors, along with the requisite movie clips. Among the interviewees are John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, Henry Fonda, Maureen O’Hara, Clint Eastwood, Martin Scorsese, and Steven Spielberg. The archival footage is quite a bit better as I’d rather here it from those who actually worked with the man.

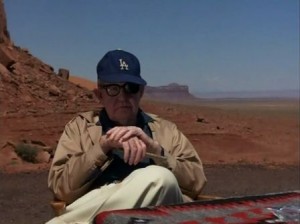

Perhaps the best part of Directed by John Ford are the portions of the film Bogdanovich shot with Ford himself, with monument Valley as a dramatic backdrop. Ford is still his crotchety self here, and you can see the stubbornness and pride for which he is known. It is also humorous as well, perhaps unintentionally so, as in response to a question on how he shot such and such a picture he responds “with a camera.” There is humor as well in that many questions clearly intended for an extended and deep discussion from the famed director are met with simple yes or no answers.

Perhaps the best part of Directed by John Ford are the portions of the film Bogdanovich shot with Ford himself, with monument Valley as a dramatic backdrop. Ford is still his crotchety self here, and you can see the stubbornness and pride for which he is known. It is also humorous as well, perhaps unintentionally so, as in response to a question on how he shot such and such a picture he responds “with a camera.” There is humor as well in that many questions clearly intended for an extended and deep discussion from the famed director are met with simple yes or no answers.

Clips from this humorous interview are also showcased in the AFI Tribute to John Ford from 1973, where Ford was presented with AFI’s first Lifetime Achievement Award. It is a formulaic and somewhat sad outing, although Ford obviously enjoyed it. Surprisingly skimpy on clips, the evening focuses instead on reminisces from some of Hollywood’s greats.

John Wayne, James Stewart, Maureen O’Hara, Jack Lemon, among others comment on some touching and sometimes humorous experiences with the great director. Wayne’s, unsurprisingly, is the most touching, as he is clearly rather emotional and ends with a simple “I could say more” as he backs away from the podium. Wayne’s introduction in Stagecoach remains one of the most iconic visuals in cinematic history.

John Wayne, James Stewart, Maureen O’Hara, Jack Lemon, among others comment on some touching and sometimes humorous experiences with the great director. Wayne’s, unsurprisingly, is the most touching, as he is clearly rather emotional and ends with a simple “I could say more” as he backs away from the podium. Wayne’s introduction in Stagecoach remains one of the most iconic visuals in cinematic history.

The entire event was hosted by Charlton Heston and emceed by Danny Kaye. In cutaway shots we see that many of Hollywood’s surviving greats (at the time) are here. Cary Grant chuckles at the right places and we also get to see Fred Astaire and Clint Eastwood as well.

Also in attendance is the current President, Richard Nixon, who makes a stirring presentation to Ford, who is clearly touched by the attention. Ford himself, makes a short speech in gratitude. Although clearly very enfeebled by this point in his life (he would pass away the same year), he walks with some assistance (the balance of the program he is wheeled in a wheelchair) to make his comments.

Also in attendance is the current President, Richard Nixon, who makes a stirring presentation to Ford, who is clearly touched by the attention. Ford himself, makes a short speech in gratitude. Although clearly very enfeebled by this point in his life (he would pass away the same year), he walks with some assistance (the balance of the program he is wheeled in a wheelchair) to make his comments.