“I don’t think I’m very much concerned with eternity. My job’s with the present.” —— Dr. Newell Paige (Flynn)

“I don’t think I’m very much concerned with eternity. My job’s with the present.” —— Dr. Newell Paige (Flynn)

In most cases when Errol Flynn steps outside of his signature roles of swashbuckler and cowboy, when he discards his sword and his Stetson hat, he errs. The actor is at his best—and one of the best on film—attired in the costume of a seventeenth-century privateer or astride a horse, with all the swagger and physical prowess these roles require. He is as right in this as are Humphrey Bogart and William Powell in their ideal niches in the twentieth century.

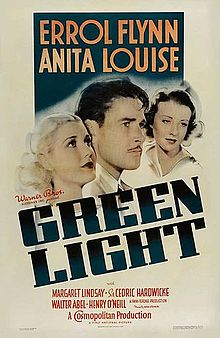

Flynn was aware of this dichotomy and of his acting limitations and said as much in assessing his part in one such atypical picture whose subject matter was foreign to his personality and sensibilities: “Green Light exacted from me a nobleness I myself cannot pretend. I am not constituted for noble sacrifice or suffering, and so I don’t think the character was really the best I could have been given. Personally I left the character . . . the moment the director told me the film was through.”

And, indeed, being slotted between two excellent Flynn films, The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936) and The Prince and the Pauper (1937)—in one on a horse, in the other sword in hand—the flaws of Green Light are agonizingly accentuated. The film, however disappointing, was enough to keep Flynn’s then fledgling career before the public. And it made money, as did another turgid, lifeless enterprise that did the actor no favors, Another Dawn (1937), which immediately followed Pauper.

And, indeed, being slotted between two excellent Flynn films, The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936) and The Prince and the Pauper (1937)—in one on a horse, in the other sword in hand—the flaws of Green Light are agonizingly accentuated. The film, however disappointing, was enough to keep Flynn’s then fledgling career before the public. And it made money, as did another turgid, lifeless enterprise that did the actor no favors, Another Dawn (1937), which immediately followed Pauper.

The Perfect Specimen that same year, with Joan Blondell, was an improvement for its type, and then followed Flynn’s stratospheric peak, The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), one of his two best films, along with The Sea Hawk (1940).

In between these two came various levels of picture-making, their quality usually determined by their genre. The better ones are The Dawn Patrol (1938), Dodge City (1939) and The Privates Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939); the lesser ones Four’s a Crowd (1938), The Sisters (1938) and Virginia City (1940). There would be other good and bad films to follow, in almost alternating perplexity, with fewer and fewer of the good, beginning in 1943.

The source novel, Lloyd C. Douglas’ Green Light, reflects the film’s high-minded subjects, with its idealistic pontifications, self-sacrifice and doing the noble thing, a drawback in itself when these ideals are conveyed without conviction. Douglas was a Protestant minister who retired at age fifty to write on moral and decidedly religious themes.

The source novel, Lloyd C. Douglas’ Green Light, reflects the film’s high-minded subjects, with its idealistic pontifications, self-sacrifice and doing the noble thing, a drawback in itself when these ideals are conveyed without conviction. Douglas was a Protestant minister who retired at age fifty to write on moral and decidedly religious themes.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the public found solace and inspiration in his uplifting themes. In that decade came a number of film transfers: Magnificent Obsession (remade in 1954), White Banners and Disputed Passage. Of his many books turned into films, the most famous is The Robe (1953). Based on one of its characters, Demetrius and the Gladiators was quickly shot in 1954. Douglas’ last filmed book, The Big Fisherman (1959), is his own sequel to The Robe.

In Green Light, rather than allow his mentor, Dr. Endicott (Henry O’Neill), to take blame for his own mistake, an idealistic young surgeon, Dr. Newell Paige (Flynn), makes a sacrifice—there’s that word!—by assuming the responsibility. He is, of course, asked to resign. He has fallen for Phyllis Dexter (Anita Louise), coincidentally the daughter of the woman (Spring Byington) who died because of Endicott’s mistake. Phyllis is naturally attracted to him—until she learns he is responsible for her mother’s death.

Paige, given a Douglas motivation to do the right thing, leaves, along with a bacteriologist friend (Walter Abel), for Montana to seek a cure for Rocky Mountain spotted fever, using himself as a guinea pig. When Phyllis learns from a surgical nurse (Margaret Lindsay), who also loves Paige, the truth about Dr. Endicott’s guilt, she goes to Montana to confess her misjudgment to Paige.

Paige, given a Douglas motivation to do the right thing, leaves, along with a bacteriologist friend (Walter Abel), for Montana to seek a cure for Rocky Mountain spotted fever, using himself as a guinea pig. When Phyllis learns from a surgical nurse (Margaret Lindsay), who also loves Paige, the truth about Dr. Endicott’s guilt, she goes to Montana to confess her misjudgment to Paige.

Meanwhile, Paige has fallen ill with spotted fever, but during a collective vigil, including Dr. Endicott, he recovers, proving the value of his new vaccine. He is reinstated at the hospital and joins Phyllis in the cathedral to hear Dean Harcourt (Sir Cedric Hardwicke) read a Psalm, supported by St. Luke’s Choristers, who will join Flynn during the coronation scene in The Prince and the Pauper. Throughout the film, the dean pontificates on spiritual guidance for all those within earshot.

For contemporary tastes, this is all too much—the moralizing and the happy ending three times over—but the Great Depression audiences were apparently uplifted by all the inspiring themes and the coming-right-in-the-end close.

Up against written material that sabotages the lead actors, the supporting players, minus most of the many famous names that had imbued both Blood and Charge, do the best they can. Anita Louise (Claude Rains’ unfortunate wife in Anthony Adverse, 1936) is nothing more than an attractive ornament. Margaret Lindsay fares less well.

Up against written material that sabotages the lead actors, the supporting players, minus most of the many famous names that had imbued both Blood and Charge, do the best they can. Anita Louise (Claude Rains’ unfortunate wife in Anthony Adverse, 1936) is nothing more than an attractive ornament. Margaret Lindsay fares less well.

Usually cast as the level-headed intellectual or stalwart man of authority, Sir Cedric Hardwicke here seems stymied by the religious and moral rhetoric he has to spout as the clergyman. Henry O’Neill is much more convincing as the namesake of the town in Dodge City, Flynn’s first Western. As mother to Louise, Spring Byington has a certain amount of appeal, largely avoiding her usual role as a scatter-brained matron or wife—she was wife to Nigel Bruce in Charge.

If undeserving of an Oscar nomination, Green Light at least has among its production team a future nominee (for Air Force, 1943), the now forgotten special effects technician Hans F. Koenekamp. Born in Iowa of German immigrant parents, he lived to be one hundred. His son, cinematographer Fred J. Koenekamp, who died in May of 2017, shot Patton (1970), Papillon (1973) and won an Oscar for The Towering Inferno (1974).

As he did frequently throughout his career, Flynn requested a change from his trademark action movies; in this case, after Blood and Charge, he wanted something more “serious.” But his acting in Green Light shows he didn’t buy for a minute this particular “change,” as further reflected in his remark that “sacrifice” and “suffering” were foreign to his character and personality.

Flynn’s amazing acting strides between Blood and Charge must have impressed even him, but surely he was also reminded, after Green Light, that his strengths were in adventure and swashbuckling. Whenever he did step outside of his comfort zone and attempted comedies, mysteries and light romances, he generally failed, as with the worst of these: Footsteps in the Dark (1941), Cry Wolf (1947) and Escape Me Never (1947).

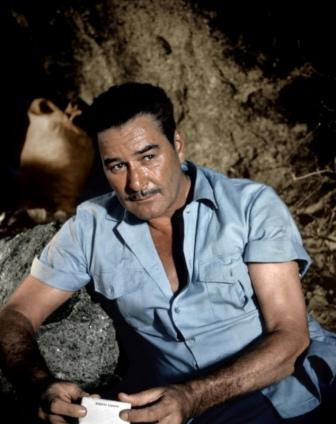

Sadly, it was only when Errol Flynn reached the decade of the 1950’s, and his own 40’s, that he came the closest to real acting, throwing aside his sword and Western hat, the bravado and the image of the great lover. With the appearance and health of a man in his late 60’s, caused by drink, drugs and dames, he settled into world-weary parts that, at last, reflected his true character and personality.

In three consecutive films during 1957 and 1958, he plays a drunk—The Sun Also Rises, Too Much, Too Soon and The Roots of Heaven. In the second he ironically plays one of his idols, John Barrymore, “The Great Profile” and drunk of the ’30s.

In the last film, director John Huston said of Flynn: “He knew he was in bad shape, but he put on a great show of good spirits.” After Huston had reluctantly agreed to take Flynn on a hunt during the African location, the director said, “I thanked heaven I’d taken him. I do to this day. He said afterward that he’d not had such a good time in years.”

Flynn would die the next year.