“Twelve people go off into a room . . . And these twelve people are asked to judge another human being as different from them as they are from each other. And in their judgment, they must become of one mind-unanimous.”——Parnell McCarthy (Arthur O’Connell)

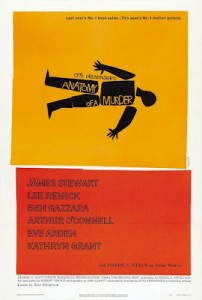

More so than in any of those Westerns directed by Anthony Mann, or in the four thrillers of Alfred Hitchcock, it is believed by many critics and movie fans that James Stewart gives the best performance of his career in Otto Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder.

In 1959, Stewart was ending his most productive decade with this film—and, also that year, The FBI Story, directed by Mervyn LeRoy. He had started the ’50s with Winchester ’73, the first of many Westerns directed by Mann, movies like Bend of the River, The Naked Spur and The Man from Laramie that would typify Stewart as a Western hero almost as much as [intlink id=”445″ type=”category”]John Wayne[/intlink], with whom he would first star in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, directed by John Ford. (Stewart would star with Wayne in Wayne’s final film, The Shootist.)

As for Hitchcock, three of Jimmy’s four films for the British director were made in the ’50s—Rear Window, The Man Who Knew Too Much and Vertigo. The fourth, and the least effective, Rope, came out in 1948.

One of the best courtroom dramas ever filmed, Anatomy of a Murder came roaring upon the scene, generally to acclaim but also to some consternation and condemnation. About a murder and rape trial, there are such words as “sperm,” “contraceptive,” “penetration” and that word of words—“panties”—that causes such titillation in the courtroom and a warning to the jury and spectators by the judge (Joseph N. Welch): “I wanted you to get your snickering over and done with. . . .

There isn’t anything comic about a pair of panties which figure in the violent death of one man and the possible incarceration of another.” The frank, forensically accurate language earned a “condemned” from the National Legion of Decency and the film was originally denied certification by the Motion Picture Production Code.

Anatomy of a Murder came at the end of a decade that saw the first critical weakening of the Production Code, or liberation from it, depending on the view, since its creation in 1930. In 1953 The Moon is Blue—also directed by Preminger—supposedly introduced such words as “mistress” and “virgin.” With The Man With the Golden Arm, again directed by Preminger, the subject was drug addiction. During the ’50s came Suddenly, Last Summer (homosexuality and cannibalism), Some Like It Hot (transvestism) and Room at the Top (adultery). The following ’60s would be even more explicit, more “morally degenerate,” or, to many, a long overdue victory over censorship.

Stewart is supported by a top-notch cast. Lee Remick and George C. Scott are the new-comers and Ben Gazzara, Arthur O’Connell, Eve Arden, Murray Hamilton and Orson Bean the old reliables. Lawyer Welch, who had called down Senator Joseph McCarthy with his famous “Have you no sense of decency, sir?” speech, is among the minor players who add flavor and realism to the screen—Kathryn Grant (Bing Crosby’s last wife), John Ford favorite John Qualen, Ken Lynch (a George Raft look/sound alike) and Howard McNear (Floyd the barber in The Andy Griffith Show). The weak star in the ensemble is Welch, who, after all, was not an actor.

Stewart is supported by a top-notch cast. Lee Remick and George C. Scott are the new-comers and Ben Gazzara, Arthur O’Connell, Eve Arden, Murray Hamilton and Orson Bean the old reliables. Lawyer Welch, who had called down Senator Joseph McCarthy with his famous “Have you no sense of decency, sir?” speech, is among the minor players who add flavor and realism to the screen—Kathryn Grant (Bing Crosby’s last wife), John Ford favorite John Qualen, Ken Lynch (a George Raft look/sound alike) and Howard McNear (Floyd the barber in The Andy Griffith Show). The weak star in the ensemble is Welch, who, after all, was not an actor.

Duke Ellington composed the jazz score, with its wailing trumpets and squealing clarinets; the film ends with staccato “peeps” on a trumpet. Ellington has one scene as “Pie-Eye,” the pianist in the Thunder Bay Inn, and Stewart briefly shares the keyboard with him.

In the opening night scene, in a part of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, Paul Biegler (Stewart), a small-town lawyer with few clients, returns from a fishing trip. He dresses his catch for the refrigerator and plays jazz on an upright piano. He is visited by his old alcoholic buddy and fellow lawyer, Parnell McCarthy (O’Connell), who, when the phone rings, tells him to say “yes” if a Mrs. Manion wants him to defend her husband. Next morning Biegler’s secretary Maida (Arden) arrives to find McCarthy asleep on the coach and quips one of those typical Arden lines: “If this refrigerator gets any more fish in it, it will swim upstream and spawn all by itself!” Later, in the courtroom, she will fire back at her boss, “You can’t fire me ’til you pay me!”

Biegler meets, first, Laura (Remick)—“You’re tall,” she purrs at Biegler—and her husband (Gazzara), U.S. Army lieutenant Frederick Manion, who is watched over in the jail by the deputy sheriff (Qualen). The lieutenant says he murdered Barney Quill because he raped his wife. Biegler explains the three ways he cannot defend him and prods the lieutenant to come up with a defensible excuse for the killing. Manion fumbles around, then opts that he was mad—no, perhaps crazy. Biegler leaves him to decide just “how crazy” and goes to interview the wife.

Biegler meets, first, Laura (Remick)—“You’re tall,” she purrs at Biegler—and her husband (Gazzara), U.S. Army lieutenant Frederick Manion, who is watched over in the jail by the deputy sheriff (Qualen). The lieutenant says he murdered Barney Quill because he raped his wife. Biegler explains the three ways he cannot defend him and prods the lieutenant to come up with a defensible excuse for the killing. Manion fumbles around, then opts that he was mad—no, perhaps crazy. Biegler leaves him to decide just “how crazy” and goes to interview the wife.

Arriving at his office, Biegler hears his jazz records playing loudly and finds the wife sprawled on his sofa, sporting tight sweater and pants and, beneath the sunglasses, a black eye. She is coquettish and somewhat naïve, an “easy” target for men as Maida observes after having just met her. Laura relates how she had innocently accepted a ride in Quill’s car, only to be assaulted and raped on a lonely back road.

In one of the film’s best scenes—this before the trial begins—Biegler is questioning Laura outside the jail in his convertible (so much more camera-friendly than an enclosed sedan). Several times the two mention “panties,” preceding the judge’s admonishment. Easy-going and flippant, even flirting with Biegler, she says she isn’t worried, that husband “Manny” will be exonerated. Biegler asks, “Would you like to have something to worry about?” “Silly,” she laughs, holding his hand. “Like,” he continues, “your husband watching us from his cell window?” (It’s a possible reflection of Stewart’s regional speech that he says “win-der”—and again during the trial.)

In one of the film’s best scenes—this before the trial begins—Biegler is questioning Laura outside the jail in his convertible (so much more camera-friendly than an enclosed sedan). Several times the two mention “panties,” preceding the judge’s admonishment. Easy-going and flippant, even flirting with Biegler, she says she isn’t worried, that husband “Manny” will be exonerated. Biegler asks, “Would you like to have something to worry about?” “Silly,” she laughs, holding his hand. “Like,” he continues, “your husband watching us from his cell window?” (It’s a possible reflection of Stewart’s regional speech that he says “win-der”—and again during the trial.)

In the same scene, Biegler asks if her husband has any reason to be jealous. Laura evasively replies that “Manny” likes to show her off and likes the way she dresses. Biegler then says, “If you think I’ve forgotten my question, I haven’t.” She says she has, and he repeats it.

In the courtroom, Biegler comes up against, as he says, “this brilliant prosecutor from the big city of Lansing,” Claude Dancer (Scott). In the trial’s climax, Dancer, aggressive from the first, suggests that Mary Pilant (Grant), who operated the roadhouse for Quill, was Quill’s lover. Her quite different revelation is the surprise of the film and decidedly weakens the prosecution’s case and helps the lieutenant get off by reason of insanity.

In the courtroom, Biegler comes up against, as he says, “this brilliant prosecutor from the big city of Lansing,” Claude Dancer (Scott). In the trial’s climax, Dancer, aggressive from the first, suggests that Mary Pilant (Grant), who operated the roadhouse for Quill, was Quill’s lover. Her quite different revelation is the surprise of the film and decidedly weakens the prosecution’s case and helps the lieutenant get off by reason of insanity.

When Biegler and McCarthy, now his new and sober law partner, drive to the Marion’s trailer park to collect their I.O.U. for services rendered, they’re in for the film’s final surprise.

1959 was the year of Ben-Hur, so a large portion of Anatomy of a Murder’s seven Oscar nominations were won by the biblical epic: Picture and Film Editing, Charlton Heston as Actor instead of Stewart (a sizeable oversight in retrospect) and Hugh Griffith for Supporting Actor, not O’Connell or Scott. Neither of the two films won for Adapted Screenplay (Room at the Top) or Black and White Cinematography (The Diary of Anne Frank). Surprisingly, Otto Preminger wasn’t nominated for Direction. The film received no Oscars. James Stewart, as something of a vindication, was judged Best Actor for his role by the Venice Film Festival, the New York Film Critics Circle Awards and the Laurel Awards.

Anatomy of a Murder dramatically conveys, in a documentary style, the procedures of the court system. But beyond this and the splendid cast—and all other pluses—the screen is dominated by James Stewart as the homespun lawyer with cool tricks and a sly understanding of the law. Stewart moves and inhabits space with a nonchalant assurance, delivering lines with myriad and subtle inflections, now humorous, now defiant, now crafty, now seemingly indifferent.

Anatomy of a Murder dramatically conveys, in a documentary style, the procedures of the court system. But beyond this and the splendid cast—and all other pluses—the screen is dominated by James Stewart as the homespun lawyer with cool tricks and a sly understanding of the law. Stewart moves and inhabits space with a nonchalant assurance, delivering lines with myriad and subtle inflections, now humorous, now defiant, now crafty, now seemingly indifferent.

Biegler is constantly alert and quick on the draw, as when the lieutenant, on their first meeting, says, “Sorry if I offended you a while ago.” Biegler, without missing a beat, says, “No, you’re not.” On the one hand, he’s docile and “interested” as Laura says of his response to her suggestive attire, yet he later forcefully drags her drunk from the roadhouse and demands she dress down to a “meek little housewife” for the courtroom.

In a dramatic plea before the judge, he compares trying to separate the motive from the act to cutting the core out of an apple without breaking the skin. “I beg the court, I beg the court, to let me cut into the apple.”

Humor abounds throughout the film. When a psychiatrist (Alexander Campbell) is introduced to the court, Biegler says, “I only wish to express my relief that the new recruit is not additional legal reinforcements from Lansing.” When bartender Paquette (Hamilton) seems uncertain about the location of a window in the bar, Biegler asks, “Well, does that window beside that table sometimes vanish and then appear again? Does it come and go in a ghostly fashion?”

Sam Leavitt’s smooth, slow-paced photography matches Stewart’s relaxed tempo. A single camera shot will linger for long periods on the actors, individually or in groups, and players sometimes move into the frame rather than break the flow by cutting. There is no quick cutting and close-ups, though used often, are deliberate and well justified.

Sam Leavitt’s smooth, slow-paced photography matches Stewart’s relaxed tempo. A single camera shot will linger for long periods on the actors, individually or in groups, and players sometimes move into the frame rather than break the flow by cutting. There is no quick cutting and close-ups, though used often, are deliberate and well justified.

When Stewart’s father heard about the nature of Anatomy of a Murder, that it was a “dirty” movie about a rape trial, he informed his son that he was telling all his friends not to see the film and even took out a newspaper notice to apologize for Jimmy’s transgression. A short time later, the father saw the movie on the sly and confessed to his son, “I saw it and I think it’s the best picture you ever made.”