“I wear the chain I forged in life! I made it link by link and yard by yard! I gartered it on of my own free will and by my own free will I wore it” —Jacob Marley to Ebenezer Scrooge

It’s getting to be that time of year. So what comes to mind? Christmas. All right. And what is Christmas all about? Shopping. Presents. Partying. All things material and of self-interest. Yes, probably for most people. There is, however, that one little old incident, something about a special birth, oh, many, many years ago, but, for me, I always think of a movie, one special seasonal movie. Its simple message is obvious, and always, always there, but few people realize it, being distracted by the assumption that it’s a mere ghost story or about a cranky old man who is as far removed from themselves as seems conceivable.

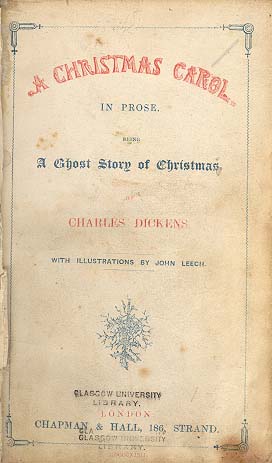

A friend of mine celebrates another holiday, Halloween, by going through all his horror films, a quite awe-inspiring collection, I understand. Me, I wouldn’t have that much time to spend glued to a TV, but around Christmas I do find the time to watch one or two of my favorite Christmas movies—and they are inevitably versions of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. One in particular, the Alastair Sim approach, made in 1951 by the British, is my supreme favorite. Its original screen title was Scrooge but for purposes here, it will be referred to by the author’s title, which should have been used in the first place.

But there have been other versions of A Christmas Carol—in fact, no fewer than five silent accounts, including one in 1910, directed by Thomas Edison. The first sound version, at least that I’m aware, appeared in 1935 with Seymour Hicks, Sir Seymour Hicks to his friends; this British film also went under the title of Scrooge. Soon after, in 1938, came an American version from M-G-M with Reginald Owen as the irascible Ebenezer Scrooge—he clearly has the down-turned mouth for it—and Leo G. Carroll, even more memorable as Jacob Marley’s ghost.

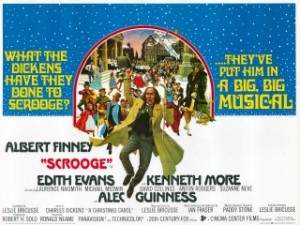

In another film titled Scrooge, Albert Finney headed the cast in a 1970 musical—British again—that included Laurence Naismith, Kenneth More, Edith Evans and Alec Guinness as Marley. (I’m prone to judge, perhaps unfairly, a satisfactory Christmas Carol on the Jacob Marley part.) In 1984 George C. Scott made a version in England, with an even more impressive British cast: Frank Finlay, Nigel Davenport, David Warner, Edward Woodward and Susannah York. The Marley part would seem a clincher for Davenport, but it went to Finlay, who, in a nice ghoulish touch, untied the chin strap (to keep the jaw closed on his corpse) with an histrionic flourish, letting his mouth drop open before beginning to speak.

In another film titled Scrooge, Albert Finney headed the cast in a 1970 musical—British again—that included Laurence Naismith, Kenneth More, Edith Evans and Alec Guinness as Marley. (I’m prone to judge, perhaps unfairly, a satisfactory Christmas Carol on the Jacob Marley part.) In 1984 George C. Scott made a version in England, with an even more impressive British cast: Frank Finlay, Nigel Davenport, David Warner, Edward Woodward and Susannah York. The Marley part would seem a clincher for Davenport, but it went to Finlay, who, in a nice ghoulish touch, untied the chin strap (to keep the jaw closed on his corpse) with an histrionic flourish, letting his mouth drop open before beginning to speak.

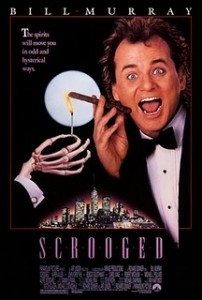

And then there are the scrimpy adaptations, the take-offs and the cartoons. Bill Murray played a modern-day Scrooge of sorts in the 1988 Scrooged. Not too successful, that; the story line was a little more than muddled, and I think it was mostly the audiences who were scrooged. The same year there was Blackadder’s Christmas Carol, with Rowan Atkinson transforming himself, now, into Ebenezer Blackadder, having put aside his roles as medieval and Elizabethan princes, dukes and archbishops, even WWI captains. Seems 1988 was a good year for the Dickens story, if “good” is applicable in all cases, for also appearing was Mickey’s Christmas Carol from Disney, at only twenty-six minutes.

And then there are the scrimpy adaptations, the take-offs and the cartoons. Bill Murray played a modern-day Scrooge of sorts in the 1988 Scrooged. Not too successful, that; the story line was a little more than muddled, and I think it was mostly the audiences who were scrooged. The same year there was Blackadder’s Christmas Carol, with Rowan Atkinson transforming himself, now, into Ebenezer Blackadder, having put aside his roles as medieval and Elizabethan princes, dukes and archbishops, even WWI captains. Seems 1988 was a good year for the Dickens story, if “good” is applicable in all cases, for also appearing was Mickey’s Christmas Carol from Disney, at only twenty-six minutes.

Not to be forgotten, though one can wonder why not, is The Muppet Christmas Carol in 1992. The ever-versatile Michael Caine tackled the “challenging” role of Ebenezer.

Not to be forgotten, though one can wonder why not, is The Muppet Christmas Carol in 1992. The ever-versatile Michael Caine tackled the “challenging” role of Ebenezer.

This partial film history of A Christmas Carol ends with the latest rendering, in 2009, another Disney production, enormously noisy, jarring special effects and somewhat chilly—and not because it took place in the winter time! Jim Carrey did Scrooge as well as the Three Ghosts of Christmas. Colin Firth, Gary Oldman and Bob Hoskins, among others, contributed some of the additional voices.

At this point, one might wonder about the obvious. What practically jumps out at you from this list? Why, that the versions are either by the British or the Americans. Why do you suppose? It may have something to do with the temperaments of the two countries, Great Britain and the United States; maybe these inhabitants are a bit more sentimental than their European counterparts, or, for that matter, the rest of the world, certainly the Asian world. Or, just possibly, maybe the Brits and the Yanks are more attuned to, in sympathy with, the residual flavor—“blot” in some cases!—of that Victorian era that fashioned the habits and morals of these people for so many years—and still does, in some sense.

The Sim version of A Christmas Carol is unquestionably the best known film by Irish director Brian Desmond Hurst, who made movies at the rate of about one a year, retiring in 1962. Richard Addinsell wrote the music, which was conducted by the prolific Muir Mathieson. As a bit of trivia, Clive Donner, the film editor, directed the Scott version thirty-three years later.

The Sim version of A Christmas Carol is unquestionably the best known film by Irish director Brian Desmond Hurst, who made movies at the rate of about one a year, retiring in 1962. Richard Addinsell wrote the music, which was conducted by the prolific Muir Mathieson. As a bit of trivia, Clive Donner, the film editor, directed the Scott version thirty-three years later.

Of the array of stars who practiced their “humbug” deliveries and donned their night caps, Alastair Sim comes as close as any to what I at least regard as the ideal image of Ebenezer Scrooge. Watching him snarl and berate and do his giddy dance on Christmas morning, I convince myself that he matches Dickens’ own concept of his creation. For one, Sim was old enough for the part, whereas, say, Albert Finney was too young, Rowan Atkinson too much of a parody and George C. Scott too robust and healthy looking.

Of the array of stars who practiced their “humbug” deliveries and donned their night caps, Alastair Sim comes as close as any to what I at least regard as the ideal image of Ebenezer Scrooge. Watching him snarl and berate and do his giddy dance on Christmas morning, I convince myself that he matches Dickens’ own concept of his creation. For one, Sim was old enough for the part, whereas, say, Albert Finney was too young, Rowan Atkinson too much of a parody and George C. Scott too robust and healthy looking.