A hard cop and a soft dame . . . do they mix?

It’s easy sometimes to confuse movies with “heat” in their titles. As far back as 1949 there is White Heat. Who can forget that final line, James Cagney screaming at the top of a flaming gas storage tank before it explodes? “Made it, ma! Top of the world!” Maintaining the criminal theme in another film almost twenty years later, Dead Heat on a Merry-Go-Round details an intricate plan to rob an airport bank.

In the Heat of the Night of 1967, and the only Oscar best-picture winner with that key word in the title, concerns a black Philadelphia detective and a hick Southern sheriff, who, at first antagonistic, unite to solve a murder.

A Technicolor film noir, Body Heat (1981) produces another kind of “heat” altogether, raging, steaming sexual passion. John Hurt smashes a set of glass doors to reach a waiting, panting Kathleen Turner. Most recently, in 2013, in contrast to all that “heat” in Body Heat, Sandra Bullock and Melissa McCarthy are buddy law enforcement officers in a comedy, The Heat.

Probably less well known than any of these titles, The Big Heat is a vintage film noir from that second surge of great noirs that came in the early 1950s. The hard, no-nonsense tone of the film, with hardly any likable characters—a noir essential—is established almost immediately by actors well trained in the genre: Glenn Ford, Gloria Grahame and Lee Marvin. Alexander Scourby, a rare screen villain and better known as a Shakespearean stage actor and the first man to record the entire Bible on LPs in the ’50s, is a cultured crime boss with a sentimental heart for his mother, though despicable nonetheless.

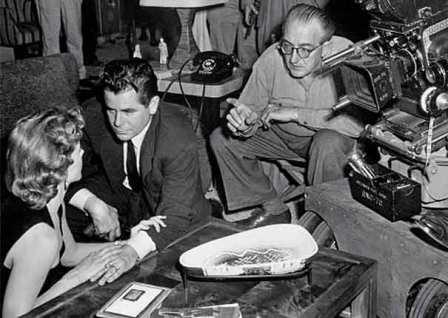

What gives The Big Heat its pace is Austrian director Fritz Lang, one of the masters of film noir. In fact, his initial American movie, Fury (1936), is conceivably the first American noir. His noir credits also include You Only Live Once (1937), The Woman in the Window (1944), Scarlet Street (1945), Cloak and Dagger (1946), House by the River (1950) and Clash by Night (1952).

What gives The Big Heat its pace is Austrian director Fritz Lang, one of the masters of film noir. In fact, his initial American movie, Fury (1936), is conceivably the first American noir. His noir credits also include You Only Live Once (1937), The Woman in the Window (1944), Scarlet Street (1945), Cloak and Dagger (1946), House by the River (1950) and Clash by Night (1952).

Lang was enamored of the script by Sydney Boehm (Rogue Cop and Black Tuesday, both 1954) and, together, they create a taunt, sometimes cruel and brutal screen edifice in The Big Heat. By implication, suggestion and cinematic slight of hand, the two men were able to slip much of the horrific brutality past the Production Code.

The screen images are heightened by the contrasting shadows and stark lighting of cinematographer Charles Lang (no relation to the director). In the most original of shots, for example, Ford might walk into the screen space, to fill a void, rather than a camera focused squarely on him. One of the most nominated of cinematographers, along with Leon Shamroy, Lang’s films include The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947), Separate Tables (1958) and Some Like it Hot (1959).

Docile and easygoing at home—a true family man, with a wife (Jocelyn Brando, Marlon’s older sister) and a little girl—homicide detective Dave Bannion (Ford) becomes a raging inferno when at work.

Docile and easygoing at home—a true family man, with a wife (Jocelyn Brando, Marlon’s older sister) and a little girl—homicide detective Dave Bannion (Ford) becomes a raging inferno when at work.

He is investigating the apparent suicide of a dishonest former cop. His wife, Bertha Duncan (Jeanette Nolan, looking decidedly duplicitous from the start), who had removed an envelope from under the dead man’s hand before the police arrived, says her husband was worried about his health. This is contradicted when Bannion later interviews the man’s mistress, Lucy Chapman (Dorothy Green).

Knowing Mike Lugana (Scourby), the big crime boss of the city, is involved, Bannion literally storms into his plush mansion. “This is my home,” he tells the detective, “and I don’t like dirt tracked into it.” After instinctively putting down a hovering henchman (Adam Williams), Bannion counters, “You know, you couldn’t plant enough flowers around here to kill the smell.”

Soon after Bannion has disregarded the warnings of his boss, Lieutenant Wilks (Willis Bouchey), to close the case as suicide, Chapman is found strangled. Then when he ignores the threatening phone calls, his wife is killed in an explosion of the family car. Bannion accuses his superiors of corruption and resigns from the department.

At a nightclub, Bannion witnesses Vince Stone (Marvin), Lagana’s lieutenant, burn the arm of a woman with a cigar, similar to burns found on Chapman’s body. The detective intimidates a belligerent Stone and he slinks away. Stone’s girlfriend, Debby Marsh (Grahame), is impressed and follows him to the hotel where he is now staying. He turns her away: “I wouldn’t touch anything of Vince Stone’s with a ten-foot pole.”

At a nightclub, Bannion witnesses Vince Stone (Marvin), Lagana’s lieutenant, burn the arm of a woman with a cigar, similar to burns found on Chapman’s body. The detective intimidates a belligerent Stone and he slinks away. Stone’s girlfriend, Debby Marsh (Grahame), is impressed and follows him to the hotel where he is now staying. He turns her away: “I wouldn’t touch anything of Vince Stone’s with a ten-foot pole.”

When she returns to the penthouse she shares with Stone, he accuses her of talking to Bannion and throws a pot of hot coffee in her face, one of the most shocking images in noir history.

After leaving the hospital, the left side of her face and neck covered in bandages, she returns to Bannion’s hotel. He takes her in, now with some degree of sympathy, brings her a tray of food and arranges for a separate, unregistered room.

In the climax, Marsh has arrived at Mrs. Duncan’s and casually notes they are “sisters under the mink” and promptly shoots her. Both women are, in fact, wearing mink coats, symbolic of an attire provided by criminals. When the dead woman’s bank box is opened, the letter she had removed from under her husband’s lifeless hand will incriminate boss Lugana.

In the climax, Marsh has arrived at Mrs. Duncan’s and casually notes they are “sisters under the mink” and promptly shoots her. Both women are, in fact, wearing mink coats, symbolic of an attire provided by criminals. When the dead woman’s bank box is opened, the letter she had removed from under her husband’s lifeless hand will incriminate boss Lugana.

At the penthouse, Marsh pays Stone back, throwing hot coffee in his face. “It doesn’t look bad now,” she taunts him, “but in the morning your face will be like mine.” He shoots her. Bannion, who has followed Stone, corners him after a short gunfight. As Marsh lies dying on the floor, she asks Bannion about his late wife. Even after he realizes she has died, he continues for a moment softly relating the endearing things he and his wife had shared.

The star emerging with all the accolades in The Big Heat is Gloria Grahame, one of her best performances, period. In the beginning, nothing more than a mobster’s moll, worried about her clothes and always preening herself, walking over the back of a sofa as if auditioning for Singin’ in the Rain (1952), Grahame gradually acquires a bit of sophistication, decorum and a heart. If there is any heat involved here, she lowers the temperature. And something more: by film’s end, when she is dying, she earns the sympathy, even a bit of tenderness, from this stoic police detective to whom she had been drawn from the first. It seemed that each wanted to help the other, but it was too late, at least for her.

With all the subtleties Grahame is able to express, it is difficult to imagine Marilyn Monroe in the role. What a poor substitute had Columbia paid the exorbitant price 20th Century-Fox was asking!

With all the subtleties Grahame is able to express, it is difficult to imagine Marilyn Monroe in the role. What a poor substitute had Columbia paid the exorbitant price 20th Century-Fox was asking!

Glenn Ford has always been able to hold his own in a variety of roles. He perhaps made more Westerns than any other genre, and is convincing on either side of the law—especially real as a killer in 3:10 to Yuma (1957) being escorted to prison. His few comedies (The Courtship of Eddie’s Father, 1963) are generally negligible, but it is in film noir that he is best remembered, and perhaps most at home: Gilda (1946), Framed (1947), The Undercover Man (1949), Mr. Soft Touch(1949), Affair in Trinidad (1952) and Experiment in Terror (1962).

Ford and Grahame were reunited in another film noir, Human Desire in 1954, and although it is directed by Fritz Lang, it is not the equal of The Big Heat in any respect.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dLLAspkOv3w[/embedyt]