Memorable Movies, Especially One, from a Time Long Gone

Another Personal Remembrance by Greg Orypeck

In growing up, most memorably in the 1950s, going to the movies was a family affair. With my mother and father, I saw South Pacific, the remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much, the warm-hearted story of Stars in My Crown, which made a lasting impression, Ma and Pa Kettle in a number of escapades and The High and the Mighty, which I saw in Moultrie, Georgia, during a family vacation in 1954, a magical year as you shall see.

The first real memories of my life are during the “good old days,” as I regard the ’50s more and more as time passes. Then there was such a thing as a double feature, plus—you might remember yourself—a cartoon or two, a news reel, a western or space serial and previews of coming “attractions,” as they were called then. This when there were three theaters downtown, in a city, then, of about 35,000.

In junior high school I struck up with a friend, and practically every Saturday morning we would meet at the grandest of the local theaters. I remember the blue-lit clock, hanging on the railing of one of those fake verandas common to art deco theaters built in the ’20s and ’30s. We would be in our seats at starting time, eleven o’clock, fortified with our favorite snacks. I don’t remember Tommy’s addiction, but my favorite was Necco wafers, chalky, quarter-size discs, about twenty-five in a roll.

In junior high school I struck up with a friend, and practically every Saturday morning we would meet at the grandest of the local theaters. I remember the blue-lit clock, hanging on the railing of one of those fake verandas common to art deco theaters built in the ’20s and ’30s. We would be in our seats at starting time, eleven o’clock, fortified with our favorite snacks. I don’t remember Tommy’s addiction, but my favorite was Necco wafers, chalky, quarter-size discs, about twenty-five in a roll.

An impressive film often prompted the purchase of the source book—or soundtrack album, if the music impressed me. I recall stopping at a record store (no longer in business) on the way home from school and buying the Capitol LP of the original Oklahoma! soundtrack with Shirley Jones. I had a crush on her at the time.

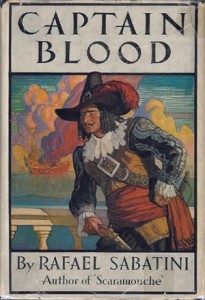

Thanks to the Hollywood studios, which sold most of their old movies to television, I gained an early—and lasting—preference for the films of the ’30s and ’40s. My first choices in film genres were costume pictures (David Lean’s Great Expectations, say) and dramas with intelligent dialogue (Dodsworth, Twelve O’Clock High, etc.), where actors actually communicated with one another and had relationships. And—oh, yes!—swashbucklers. My insistence on fine acting, and the likes of Spencer Tracy and Ingrid Bergman, was suspended for swashbucklers; here the expert flourishing of a sword by Errol Flynn, Tyrone Power or Stewart Granger was sufficient. And, besides, swashbucklers usually had the best scores.

Not surprising, then, Captain Blood, made in 1935 by Warner Bros., remains my all-time favorite film. [See the separate review of Captain Blood.] I first saw it in a 1952 re-release at another of the city’s theaters, long since replaced by a parking garage. What I still appreciate about the movie was what sparked my teenage imagination—the saga of the sea and the romance of sailing ships, passions that still remain. The setting in a by-gone era—the 17th-century Caribbean—instinctively fascinated me. Childhood escapism? Perhaps.

Not surprising, then, Captain Blood, made in 1935 by Warner Bros., remains my all-time favorite film. [See the separate review of Captain Blood.] I first saw it in a 1952 re-release at another of the city’s theaters, long since replaced by a parking garage. What I still appreciate about the movie was what sparked my teenage imagination—the saga of the sea and the romance of sailing ships, passions that still remain. The setting in a by-gone era—the 17th-century Caribbean—instinctively fascinated me. Childhood escapism? Perhaps.

Director Michael Curtiz’ shadows-on-the-wall trademark struck an impressionable movie-goer as “neat” and artistic. And the music of Erich Wolfgang Korngold, whether brilliant or melodic, supported the screen with a symphonic opulence unknown in film scores of the time, or since. This first taste of Korngold led me eventually to discover his output of so-called “serious” music.

In deference to Shirley Jones, in Captain Blood I had found my first true love: Olivia de Havilland. She was Peter Blood’s girlish goddess, demure and virginal, qualities I subsequently required in my leading ladies. Ingrid Bergman, eventually to become—and remain—my favorite actress, also met these criteria, despite her licentious look in a few roles.

The novel Captain Blood was forthwith ordered from Benford’s, a stationery store also gone. The stilted dialogue of Sabatini’s novel, preserved in the film by screen writer Casey Robinson, was seductive to a budding “writer”—and stylistically disastrous. Well, hopefully, not completely so! The book, from Houghton Mifflin, was $3.00! Opening it recently after many years, I discovered brown stains on the pages. The chemical action in the paper I don’t understand, but the message in the stains is clear: TIME IS PASSING, and not just for the book.

The novel Captain Blood was forthwith ordered from Benford’s, a stationery store also gone. The stilted dialogue of Sabatini’s novel, preserved in the film by screen writer Casey Robinson, was seductive to a budding “writer”—and stylistically disastrous. Well, hopefully, not completely so! The book, from Houghton Mifflin, was $3.00! Opening it recently after many years, I discovered brown stains on the pages. The chemical action in the paper I don’t understand, but the message in the stains is clear: TIME IS PASSING, and not just for the book.

Only one film in my memory bank had a negative effect on me. It’s a vivid memory, after all these years, the way the best of good memories are vivid. In short, it struck terror in the heart of a nine-year-old who didn’t like bad things to happen to people in movies. An uncle of mine, a retired U.S. Army major, took his son and me to see He Walked By Night. This in 1948. Richard Basehart plays a criminal who escapes through the city sewers. In the most horrific scene in the film, Basehart has been shot and returns to his apartment, where, looking in a mirror, he probes and grunts and grimaces as he removes a bullet from his side. I still hear myself begging, “Let’s go! Let’s go!” I’m sure half the audience heard me. My uncle, however, didn’t make a move. He was, after all, one of those “hard” Army majors, and I saw all of He Walked By Night!

Only one film in my memory bank had a negative effect on me. It’s a vivid memory, after all these years, the way the best of good memories are vivid. In short, it struck terror in the heart of a nine-year-old who didn’t like bad things to happen to people in movies. An uncle of mine, a retired U.S. Army major, took his son and me to see He Walked By Night. This in 1948. Richard Basehart plays a criminal who escapes through the city sewers. In the most horrific scene in the film, Basehart has been shot and returns to his apartment, where, looking in a mirror, he probes and grunts and grimaces as he removes a bullet from his side. I still hear myself begging, “Let’s go! Let’s go!” I’m sure half the audience heard me. My uncle, however, didn’t make a move. He was, after all, one of those “hard” Army majors, and I saw all of He Walked By Night!

It’s difficult to write about one of life’s milestone experiences. In approaching the story of, not my favorite movie in this case, but the most influential, I wonder if I can recapture the excitement of that afternoon and evening so long ago. Recapture the memory for myself, yes, but to convey it—— No, no way. But I’ll try. . . .

It happened by chance. It was that wonderful year, 1954. I was fifteen and in the ninth grade at the junior high where my mother taught seventh grade English. I rode to school with her but would usually walk the three miles home, often with some friends. The excursion might have been an adolescent need to be independent of Mom and Dad, although I never recall being embarrassed to be seen with my parents.

For several weeks a certain Disney movie had been playing at that grand art deco theater in town. I had thought of going—a sea adventure, it sounded like my kind of film—but decided against it. Then the engagement, proving to be an enormous hit, was extended two weeks. Okay, then, I’ll go. I told Mom I’d catch the three o’clock show and walk home; I should be home in time for supper at six.

For several weeks a certain Disney movie had been playing at that grand art deco theater in town. I had thought of going—a sea adventure, it sounded like my kind of film—but decided against it. Then the engagement, proving to be an enormous hit, was extended two weeks. Okay, then, I’ll go. I told Mom I’d catch the three o’clock show and walk home; I should be home in time for supper at six.

What I experienced was, in short, the most impressive, exciting, spell-binding, original movie a fifteen-year-old had ever seen. It was 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. I was mesmerized from the start, with the lifting of an undersea curtain (to the strains of the opening title, below) and the emergence of a gold-lettered book, which magically opened to Chapter I: “ . . . vessels had been met by ‘an enormous thing’ . . . ” Something was harassing the shipping lanes in 1866! The action that followed was non-stop, from the moment a steamship is sunk to the destruction of a secret island.

To fully appreciate my excitement and the ambiance of the film, you need to recall a bit of your own childhood. For me, it was a “boy’s film” of its day—adventure, heroics and no women—but since 1954 I’ve realized it is far more than that. No previous film, for example, had had such extensive and beautiful underwater photography, not even Beneath the 12-Mile Reef made the year before. The underwater scenes, which included a funeral and a long sequence involving food-gathering, sunken ship exploration and a shark attack, were filmed in the crystal-clear waters off the Bahamas, “crystal-clear” as Life magazine described them in at least two feature articles.

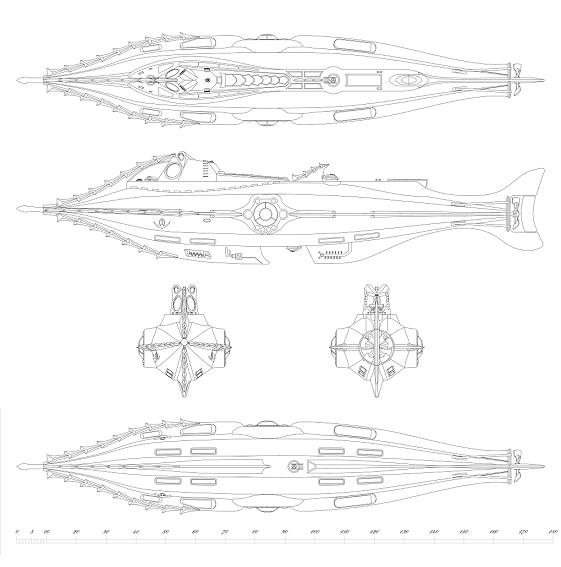

James Mason was magnificent as the cultured Captain Nemo, even playing the organ, but the star of the film was Jules Verne’s serpent-shaped “Nautilus,” a design fusion of shark and crocodile, as its creator, Harper Goff, had said. During the two-hour movie, the submarine rammed and sank several ships, ran aground on a reef, was boarded by cannibals, nearly sunk by a warship and attacked by a giant squid.

The first version of the squid fight was deemed unexciting and tacky by Walt Disney—unexciting because the submarine was surfaced in a calm, daylight sea and tacky because of the ridiculously unconvincing squid, with visible puppet lines for tentacle movement. Disney ordered director Richard Fleischer to reshoot and rethink the episode, this time in a raging storm and with a totally redesigned squid, the tentacles now pneumatically operated. The sequence became the highlight of the film and the main reason it won the Special Effects Oscar.

In 1954 main features were shown continuously, without the lights coming up, the audience cleared or the floor swept. Hypnotized by the first viewing of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, I remained to see it again—and a bit of a third time, up to where the “Nautilus” rams the “Abraham Lincoln,” the vessel sent to find the monster.

In 1954 main features were shown continuously, without the lights coming up, the audience cleared or the floor swept. Hypnotized by the first viewing of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, I remained to see it again—and a bit of a third time, up to where the “Nautilus” rams the “Abraham Lincoln,” the vessel sent to find the monster.

As I walked home that night—by then it was around eight-thirty—those vibrant, colorful images lingered, including the music. I constantly hummed the main melody, chromatic and appropriately murky, afraid, I guess, of forgetting it, as if forgetting the tune would destroy the whole experience. In the depths of a lake that was on my route, I could see the yellow “eyes” (actually the conning tower lights) of the “Nautilus.” Daaa-da-dee-da-dee-dum——

You can imagine my parents’ mood when I finally did walk in the front door. “Where have you been?” asked my mother. “Do you know how worried we’ve been?” said my father. I don’t remember if they had called the police. Seems like they had. I don’t recall, either, any punishment. Only the exhilaration of an esthetic revelation.

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea immediately became an obsession, not surprising since obsessions are a personality trait. While fresh in the memory, I wrote a detailed account of the film. I bought two games and several copies of the Disney comic book, compiled a scrapbook of numerous magazine articles, devised a 387-question quiz and recreated the interior of the “Nautilus” inside two large cardboard boxes. And that’s not all—

An elderly couple, who lived across the street on a slight incline, could look down our opposite driveways, through our carport and into my father’s double-car garage, where I was working furiously. “What is Greggy doing?” the man asked my mother.

I was building the “Nautilus”—of course! Working from a foundation of two long-necked bottles, base-to-base, I used papier-mâché to shape the submarine, carefully forming the individual “teeth” on the fore structure. From Mom’s sewing basket I borrowed two pearl buttons for the conning tower windows and a smaller one for the forward hatch, a propeller from an unseaworthy ship model and toothpicks to hold the tail fin support. And it was all painted a dark green, a blend of black and green paint, which my father unknowingly contributed. Like Henry Drummond’s rocking horse Golden Dancer in Inherit the Wind, “ . . . it was a dazzling sight to see,” only more resilient.

I was building the “Nautilus”—of course! Working from a foundation of two long-necked bottles, base-to-base, I used papier-mâché to shape the submarine, carefully forming the individual “teeth” on the fore structure. From Mom’s sewing basket I borrowed two pearl buttons for the conning tower windows and a smaller one for the forward hatch, a propeller from an unseaworthy ship model and toothpicks to hold the tail fin support. And it was all painted a dark green, a blend of black and green paint, which my father unknowingly contributed. Like Henry Drummond’s rocking horse Golden Dancer in Inherit the Wind, “ . . . it was a dazzling sight to see,” only more resilient.

The 16-inch model, with only minor wear, is now in my music room on a shelf beneath a poster for the film. Actually the poster is the cover from the press book, a gift from a friend who worked in the 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea exhibit at Disneyland. Much later, a friend in Wisconsin felt “everyone should have their favorite movie” and sent me the film on VHS. Then one of my sons gave me a pirated CD of the original soundtrack, minus “A Whale of a Tale,” which Kirk Douglas sings in the film.

Fulfilling something close to a dream, a restored DVD version of the film, with features unimaginable in those “primitive” ’50s, was issued some years ago on two discs. There were interviews with Fleischer and visual effects artist Peter Ellenshaw, both of whom had died by the time the film was reissued, now on a single DVD. Time, indeed, had moved on for those two artists and 2009—already!—is the fiftieth-fifth anniversary of the première of the film.

One last point, a particularly important one—why the movie is the most influential in my life. That first of two pieces Mason plays on the organ? When I first saw the film—and the times I saw it again and again, dragging my parents on one occasion—the awareness of the organ music must have lingered dormant in my subconscious. Then one Sunday morning in church the organist played a familiar postlude. It was from the film! Hands shaking, I checked the program.

Perhaps not as naïve as Vivien Leigh, who at the Atlanta première of Gone with the Wind heard a band strike up “Dixie” and gasped, “Oh, they’re playing the tune from the picture!,” I knew the J. S. Bach hadn’t been composed anew for 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea! Indeed, that chance Sunday hearing was Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, BWV565, distinct, now, from another piece with identical title and key, called the “Dorian,” BWV538.

Perhaps not as naïve as Vivien Leigh, who at the Atlanta première of Gone with the Wind heard a band strike up “Dixie” and gasped, “Oh, they’re playing the tune from the picture!,” I knew the J. S. Bach hadn’t been composed anew for 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea! Indeed, that chance Sunday hearing was Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, BWV565, distinct, now, from another piece with identical title and key, called the “Dorian,” BWV538.

Before I owned a record player—then I didn’t know Bach from Bartók—I acquired the LP and listened to the Bach on various friends’ players, until my father bought me one of my own. It had been a slow, perhaps subliminal process, beginning with Jesse Crawford playing organ music on 45 r.p.m. records, gifts from my mother, and passing through Korngold’s Captain Blood, but with 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, I had discovered something greater, far more persuasive than even the movies: I had discovered classical music.

But that’s another story.