“If I were not mad, I could have helped you. . . . And because I’m mad, I’m rejoicing in my heart, without a shred of pity, without a shred of regret, watching you go with glory in my heart!” — Paula Anton to her husband

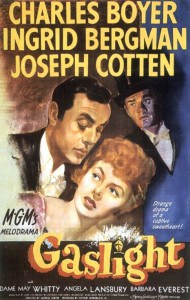

Any film starring Ingrid Bergman gets my attention. M-G-M’s Gaslight has always been a favorite, although often disparaged by some critics as inferior to the earlier British version, I’m not sure why. Cary Grant, I think it was, once remarked that Ingrid should receive a special Oscar every year, whether Ingrid was nominated or not. It’s true that in the mid-1940s, at the height of her popularity and when she made her best films, she was always being nominated as Best Actress.

Before the topic turns to Gaslight, her Oscar nominations, though deserved compared with her competition, have often been for the wrong films. Take 1945 for instance when she was nominated (without winning) for The Bells of St. Mary’s, an innocuous bit of sentimental fluff. In the spirit of the times, such Oscar nods came simply because by then she was an enormous box office draw—Ingrid Bergman, after all, a luscious screen image. In 1946 she wasn’t nominated for Notorious, one of her two best performances, and she clearly deserved a nomination over Jennifer Jones’ groveling-in-the-dirt half-breed in Duel in the Sun. (Olivia de Havilland was an agreeable win that year for To Each His Own.)

Then there’s the second of her two greatest performances, Ilsa in Casablanca in 1943. She was nominated that year, not for Casablanca but for a less memorable role, Maria in For Whom the Bell Tolls. (Like Laurence Olivier, maybe she felt changes in physical appearance—the short haircut in Bell—was an essential part of the acting process, a supposed “challenge.”) In 1956, the Anastasia win was a welcome-home-Ingrid-we-forgive-you award after her “misbehavior” with Roberto Rossellini. Maybe, too, Hollywood felt just a little ashamed of its own behavior toward her.

Now, a naïve wife preyed upon by a duplicitous husband, the Bergman version of Gaslight is another of the actress’s many “good girl” roles. Among the few exceptions is Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. She turned down the morally upstanding role—that of Spencer Tracy’s fiancée—originally assigned her and saw greater potential in the role of the prostitute, intended for Lana Turner (Lana blandly played the fiancée). Ingrid’s last Oscar, now for Supporting Actress, came in 1974 for Murder on the Orient Express. Once again she eyed a role other than the one planned for her, not director Sidney Lumet’s choice of the old Russian princess (eventually played by Wendy Hiller) but that of the mousy Swedish missionary.

Now, a naïve wife preyed upon by a duplicitous husband, the Bergman version of Gaslight is another of the actress’s many “good girl” roles. Among the few exceptions is Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. She turned down the morally upstanding role—that of Spencer Tracy’s fiancée—originally assigned her and saw greater potential in the role of the prostitute, intended for Lana Turner (Lana blandly played the fiancée). Ingrid’s last Oscar, now for Supporting Actress, came in 1974 for Murder on the Orient Express. Once again she eyed a role other than the one planned for her, not director Sidney Lumet’s choice of the old Russian princess (eventually played by Wendy Hiller) but that of the mousy Swedish missionary.

Although good girl roles comprise most of her career—in Bells of St. Mary’s, Spellbound, Joan of Arc, Anastasia, The Inn of the Sixth Happiness, etc.—there were also the falls from grace, so to speak. In Goodbye Again she is a middle-aged woman having an affair with a young man (Tony Perkins), in Saratoga Trunk she plays a coquette to a cowboy (Gary Cooper) and in Stromboli she offers money for someone to kill a lover (Anthony Quinn)—all films, incidentally, unworthy of her talents. And the obvious conclusion? Maybe she is at her best in good girl roles—and good girls in jeopardy are better still. This is where Gaslight comes in—and that justified Oscar.

The film is something of a mystery within a mystery. It opens at No. 9 Thornton Square, London, 1875. The child Paula is leaving the house where her aunt, a famous opera singer, Alice Alquist, was inexplicably murdered. Several sources indicate that the fourteen-year-old Paula, escorted from the house on the arm of Mr. Muffin (Halliwell Hobbes), is played by Terry Moore, but—and I’ve checked the film several times—to me the girl looks awfully like Ingrid herself.

We must assume time has passed in the obligatory manner of Hollywood, here without time lapse scenes of seasonal changes, and Paula, now a grown woman, is in Italy. An aspirant singer, she is taking lessons, singing an aria from Donizetti’s “Lucia di Lammermoor.” After the lesson, she meets her lover Gregory Anton (Charles Boyer), who was, in fact, her piano accompanist.

Ingrid writes in her autobiography, My Story, “The next difficulty [the first was Boyer getting top billing] came with the first scene we shot. I have always pleaded with my directors: ‘Please, please don’t start the film with a love scene.’ . . . And with Charles Boyer, it was absurd! Our opening shot, out of sequence as always, was when I arrived at a railway station in Italy. I leapt out of the carriage and raced across to where Charles was standing . . . No woman in her right mind would object to being kissed by Charles Boyer, but I had to do all the running because . . . [he was] perched on a ridiculous little box since I was quite a few inches taller than he. So I had to rush up and be careful not to kick the box, and go into my act. It was easier for us to die of laughter than to look like lovers.”

Ingrid writes in her autobiography, My Story, “The next difficulty [the first was Boyer getting top billing] came with the first scene we shot. I have always pleaded with my directors: ‘Please, please don’t start the film with a love scene.’ . . . And with Charles Boyer, it was absurd! Our opening shot, out of sequence as always, was when I arrived at a railway station in Italy. I leapt out of the carriage and raced across to where Charles was standing . . . No woman in her right mind would object to being kissed by Charles Boyer, but I had to do all the running because . . . [he was] perched on a ridiculous little box since I was quite a few inches taller than he. So I had to rush up and be careful not to kick the box, and go into my act. It was easier for us to die of laughter than to look like lovers.”