“A little girl in a cage, waiting for someone to come along and let her out.”—— Walter O’Neil to his wife, Martha

In any academic overview, it could be assumed that war movies, usually aimed at boosting Allied propaganda, were the most prolific film genre during the first half of the 1940 decade. Most abundant, yes, but, although there were any number of masterpieces, others—it’s tempting to say the greater majority—were forgettable, seen in retrospect and in saner times as biased and, worse, now embarrassingly racist.

Whatever due they deserve, war films have been far eclipsed by the most lasting and influential genre of their time, the whole decade of the ’40s, and that is film noir. These films concern, in the briefest summary, desperate people in desperate situations, photographed in a gloomy atmosphere and in black-and-white.

In more comprehensive terms, the individuals are usually—almost necessarily—among the lower rungs of society, the down-and-outers, if not criminals of some sort, then nearly so, caught up in some malice beyond their control. And whether guilty or not of what threatens them, they are the clear-cut victims. Even the wealthy and well-positioned are subject to this cruel intrigue, for their status is corrupted by their faults and flaws, just as often by the evil of others. If they escape at the end of the last reel, they escape forever scarred.

The scholars have so decreed—and it seems a convenient peg to hang the obvious—that all this angst in film noir developed out of any number of world-wide crises, mainly during and just before the ’40s, as early as World War I, if one cares to backtrack that far for symptoms. Subsequent to that tragedy came the Great Depression of the ’30s; then another global war, only worse than the one before; after a supposed victory, a Cold War and the terror of possible nuclear annihilation; in the mid-’50s, the McCarthy communist witch-hunt; and even now, for the terror never abates, only erupts in different guises, a new confection of calamities. From an unwanted—would it be perverse to say “rich”?—source, the noir filmmakers, like their fellow artists, the playwrights, novelists, even opera composers, made their creations a subtext against the infringement of liberties and the abuse of government power.

Today film noir continues in a fashion, more often now, though always less dynamic, a further dilution of the genre, in color. For some inexplicable reason, against all artistic and dramatic logic, nobody wants to watch B&W films, and just about as large a majority of Hollywood powers-that-be disdain making non-color films, mainly because they reduce attendance.

The oppressive, claustrophobic nihilism of film noir began, some would like to think, with a convenient milestone in the detective genre, The Maltese Falcon of 1941. Although its director, John Huston, would guide two other notable gangster noir films, Key Largo and The Asphalt Jungle, it was the Austrian Fritz Lang who came to be especially associated with the genre, even three exceptional films that predate Falcon—M (in Germany) in 1931, Fury in 1936 and You Only Live Once in 1937. He held his own in the field throughout the ’40s and ’50s, and toward the end of his career, in 1956, turned out one of the best noirs, While the City Sleeps. Even the title is great!

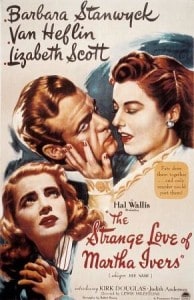

So, with all this as way of introduction, comes, in 1946, The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, directed by Lewis Milestone. Though not remembered for film noir, but better known for All Quiet on the Western Front and, some say, the “notorious” 1962 remake of Mutiny on the Bounty, the director made Ivers as representative and as crafty a movie of the type as did most other directors—and they all seemed to try their hand with at least one of these dark films.

Although not here connected with Warner Brothers where he did his finest work, producer Hal B. Wallis in Ivers (distributed by Paramount) delivers his reliable stamp of quality and studio sheen. Cinematographer Victor Milner, adept in both B&W and color, captures the milieu of dark mansions, seedy hotel rooms, the abundant rainy exteriors, nightclub table talk, dark alleys, bus stations and lonely highways—all standard settings for film noir.

Not one of his best scores, Miklós Rózsa does, nevertheless, reinforce the shadows, the slugfests, the seemingly perpetual rain, the intrigues and, above all, that peculiar love of Martha Ivers. Like other composers who specialized—Max Steiner in Bette Davis melodramas, Erich Wolfgang Korngold in swashbucklers, Dimitri Tiomkin in Westerns—Rózsa best demonstrates his gifts, the biblical epics aside, in film noir. In fact, he scored many of Hollywood’s greatest films in the genre: Double Indemnity, The Red House, The Lost Weekend, Lady on a Train and, yes, Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle, and, not to be forgotten, the trilogy produced by Mark Hellinger: Brute Force, The Killers and The Naked City.

Unlike a number of Rózsa’s scores, in Ivers there is no set piece or big tune to grab the ear of the movie-goer. There is, for example, the cello melody for Mouche (Anne Baxter) in Five Graves to Cairo, the waltz in Madame Bovary, all those marches in Quo Vadis? and Ben-Hur, the voyage music in Plymouth Adventure and the piano solos in Lydia. Speaking of the piano, in the so-called “concerto” connection with Hitchcock’s Spellbound, that instrument was only used in a special synthesis of the score arranged by the composer apart from the film.

The musical signature of Ivers is a typical Rózsa trademark, a motif driving the tension and passion throughout much of the movie, either in the forefront to sharpen the action or beneath dialogue to emphasize the menacing duplicity. These few notes, endlessly repeated with shifting emphasis, represent this “strange love of Martha Ivers.”

But for whom is her love extended, anyway? No one is sure. Is it a shield against her being hurt, or called up at will for her own selfish protection? Her husband she obviously doesn’t love. Toward the stranger she once knew as a teenager, who returns eighteen years later as an adult, she gives the initial impression that he was her true love, that she still loves him. But like a double-edged sword, this “love” turns to thoughts of murder when her power, reputation and life are threatened. But this is touching upon the plot. . . .

But for whom is her love extended, anyway? No one is sure. Is it a shield against her being hurt, or called up at will for her own selfish protection? Her husband she obviously doesn’t love. Toward the stranger she once knew as a teenager, who returns eighteen years later as an adult, she gives the initial impression that he was her true love, that she still loves him. But like a double-edged sword, this “love” turns to thoughts of murder when her power, reputation and life are threatened. But this is touching upon the plot. . . .

The Strange Love of Martha Ivers begins in 1928—in the rain. (Rain here is as much a presence as any of the human characters.) A defiant, runaway teenager, Martha Ivers (stiffly played by Janis Wilson), having been caught once again by the police, is reprimanded by her domineering aunt (Judith Anderson). Her young friend, Sam Masterson (Darryl Hickman), who had shared the escape attempt with her but had eluded the police, returns and crawls in through a window out of the rain.

When the aunt strikes Martha’s pet cat with her cane, Martha grabs the stick and hits her, sending her rolling down a winding staircase, dead. Walter O’Neil (Mickey Kuhn), another young friend, is witness to the act and corroborates her lie that the assailant was a man she said ran out the front door. Walter’s father (Roman Bohnen, also Dana Andrews’ father in The Best Years of Our Lives), obviously doubting her, instructs the two children to stick to Martha’s story when the police come. He has his own ulterior motives, to protect his interests in the Ivers family, which owns the mill and runs the community, so much so that it’s named Iverstown. As the result of Martha’s testimony at the trial, an innocent man is hanged.

When the aunt strikes Martha’s pet cat with her cane, Martha grabs the stick and hits her, sending her rolling down a winding staircase, dead. Walter O’Neil (Mickey Kuhn), another young friend, is witness to the act and corroborates her lie that the assailant was a man she said ran out the front door. Walter’s father (Roman Bohnen, also Dana Andrews’ father in The Best Years of Our Lives), obviously doubting her, instructs the two children to stick to Martha’s story when the police come. He has his own ulterior motives, to protect his interests in the Ivers family, which owns the mill and runs the community, so much so that it’s named Iverstown. As the result of Martha’s testimony at the trial, an innocent man is hanged.

The crux of the tale, and what motivates Martha and Walter in the years to come, is the belief that Sam was a witness to the murder. In truth, he had left before the incident, to board an outbound circus train.

In the next scene, it is 1946. Sam Masterson (now Van Heflin), an itinerant gambler, passing near Iverstown for the first time in eighteen years, is forced to stay over because of a car accident. (The uncredited actor who slept through the mishap is Blake Edwards.) Sam discovers from the garage manager (Walter Baldwin) that Martha (Barbara Stanwyck) and Walter (Kirk Douglas) have united in a joyless marriage. Martha runs mill and town, and Walter is the district attorney, a weakling and a drunk, the pawn of his wife.

In the next scene, it is 1946. Sam Masterson (now Van Heflin), an itinerant gambler, passing near Iverstown for the first time in eighteen years, is forced to stay over because of a car accident. (The uncredited actor who slept through the mishap is Blake Edwards.) Sam discovers from the garage manager (Walter Baldwin) that Martha (Barbara Stanwyck) and Walter (Kirk Douglas) have united in a joyless marriage. Martha runs mill and town, and Walter is the district attorney, a weakling and a drunk, the pawn of his wife.

While his car is being repaired, Sam meets Toni (Lizabeth Scott), who was waiting for a bus out of town. Recently released from jail, she easily qualifies as a noir resident. The two begin a relationship, sharing the bathroom between their two hotel rooms—this is Production Code days! In one of the signal images of ’40s films, they do a lot of shared smoking, lighting and passing cigarettes to one another, in all places, especially cars.

From all appearances, Martha and Sam are warmly reunited in Walter’s office. Sam’s effusion is sincere; beneath her guarded exterior is that erroneous assumption that he knows about the murder. Husband and wife are immediately wary. Why would Sam return to Iverstown, they decide, unless to blackmail them? Walter sends some thugs to encourage Masterson’s departure. Sam’s own suspicions are aroused and he visits the local newspaper office, learns about the murder, puts two and two together.

There have been earlier clues that Sam has a shady past of his own. For one, it’s his gambler’s lifestyle, the way he talks; for another, he is pursued by the police because of an earlier self-defense death. What certifies Sam as a member of this noir tale is that, realizing Martha had murdered her aunt, he threatens blackmail—fifty per cent of her company. Martha plays up to her possible partner, proposing that they kill Walter. To his credit, Sam balks at sinking this low.

After a fight with Walter, Sam leaves the mansion. Looking back, he sees the couple in an upstairs window. Inside, Walter has turned the gun on Martha. She puts her finger on his trigger finger and presses. She dies and Walter turns the gun on himself—all a required dictum of the ever-watchful Production Code and a variation on the outcome of any number of film noirs.

Sam and Toni leave Iverstown. For better or worse? Who knows. Their lives scarred certainly, their future together uncertain.

Sam and Toni leave Iverstown. For better or worse? Who knows. Their lives scarred certainly, their future together uncertain.

This was [intlink id=”242″ type=”category”]Kirk Douglas[/intlink]’ first film. Despite the role of a weakling and otherwise unlikable character, he is able to convey an almost hidden, protected love for his horrid wife and receive more than a bit of sympathy from the audience. In holding the screen, he in no respect comes up short against his two co-starring veterans, Stanwyck and Heflin. Speaking of film noir, his next picture, Out of the Past, with [intlink id=”46″ type=”category”]Robert Mitchum[/intlink] and Jane Greer, proved to be one of the most satisfying films of the genre. In another film of the type, I Walk Alone (1948), Douglas would be reunited with producer Wallis and actress Scott, here playing a more positive character as a nightclub singer.

Barbara Stanwyck had made a tentative star breakthrough in Stella Dallas in 1937 and two indisputable ones in Double Indemnity in 1944 and Sorry, Wrong Number in 1948. In comparison with the former, in Ivers she is equally despicable, but now exhibiting greater range and nuance, her mood swings—I love you, I love you not—bordering on the schizophrenic. The predator here, only two years later she would become the prey of a killer husband in the overblown The Two Mrs. Carrolls with [intlink id=”189″ type=”category”]Humphrey Bogart[/intlink].

Barbara Stanwyck had made a tentative star breakthrough in Stella Dallas in 1937 and two indisputable ones in Double Indemnity in 1944 and Sorry, Wrong Number in 1948. In comparison with the former, in Ivers she is equally despicable, but now exhibiting greater range and nuance, her mood swings—I love you, I love you not—bordering on the schizophrenic. The predator here, only two years later she would become the prey of a killer husband in the overblown The Two Mrs. Carrolls with [intlink id=”189″ type=”category”]Humphrey Bogart[/intlink].

This was Van Heflin’s first film after war service in the U. S. Air Force, and he commands the screen as if he had never left Hollywood. His performance, in fact, is perhaps the most fascinating of the four major roles, clearly the one with the most humor. He interacts with practically every character in the film, including, especially, his almost exclusive partner, Scott. He, too, would appear in another later film noir, Possessed with Joan Crawford, another screen femme fatale, though less versatile than Stanwyck.

And as for Lizabeth Scott, for someone who made so few movies, she made enough film noirs to become, now, an unofficial female symbol of the genre, and one of the few survivors of the ’40s and ’50s era. As a possible male counterpart who made his share of film noirs, though none as her co-star, Dana Andrews conveys the same kind of cold honesty, even in his dishonesty. They both had the stoic look and low-key acting style that befit these kinds of films, the film noir that helped make going to the movies such a memorable experience in the middle of the twentieth century.

Literary Postscript.

Apropos to this discussion of film noir and The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, Applause Theatre & Cinema Books has generously sent our website a copy of their 2013 publication of David J. Hogan’s Film Noir FAQ. It has the somewhat convoluted subtitle, All That’s Left to Know About Hollywood’s Golden Age of Dames, Detectives, and Danger. Although the publishers seem to concentrate on rock and heavy metal groups—The Beach Boys, Led Zeppelin and Bruce Springsteen—there is TV and movie fare on such diverse topics as Lucille Ball, Doctor Who, James Bond and Star Trek.

The Film Noir FAQ author, who also has an FAQ book on the Three Stooges (quite a leap from film noir!), writes in a serviceable style, with a flare for the occasional unique expression and deft turn of phrase. In discussing the movies, his broad film knowledge is a plus in intertwining references to, say, screenwriters and cinematographers with other related films and artists, tie-ins that make the reading all the more enjoyable.

The somewhat unusual layout of the book may seem awkward at first, but once the plan is understood, things will come together more coherently. The chapters are headed with such titles as “The Private Dick” and “Victims of Circumstance,” with discussions of individual films—mainly plot summaries and historical backgrounds—taken in chronological order within each chapter. The individual movie studies, however, are headed by catch phrases—for example, the film The Unsuspected is under “Technology That Kills” and The Woman in the Window under “Old Enough to Know Better.” This way, it’s less easy to find a looked-for movie and an index search for a specific title is often necessary.

Interspersed within this text are what the author calls “case files,” thumbnail portraits of stars, directors, screenwriters and cinematographers (no composers!) mentioned in the adjacent discussion. The two writings are set in different fonts, though about the same size type, and separated by gray bars; if the case files had been in boldface, or in a box, there would have been a better contrast. This juxtaposition may be a dilemma for some readers: do they stop reading the main text to peruse the thumbnail or come back when they have finished the text? These sketches are always embedded within the text, never at the end. An enlightening feature, though.

To those who feel the score is an essential part of film noir’s dark milieu, the book falls short of its subtitle claim of “all that’s left to know.” Hogan hardly ever mentions the music supporting the drama on screen. How can any one write about film noir, purporting an encompassing authority, and ignore the scores of Steiner, Waxman, Rózsa, Deutsch and all the others that have, through the years, reinforced the weight, and horror!, of the noir experience? Why, there’s not one index reference to Rózsa! And Roy Webb, who scored even more of the genre, has one meager comment, that regarding Murder, My Sweet, however true: “ . . . a splendid score by the perennially underrated composer Roy Webb . . . ” What about his scores for Notorious, The Window, Out of the Past and all the other movies the author discusses, sans the music?

Another writer on movies once responded to another censure for ignoring the contribution of music, this time that for Errol Flynn swashbucklers, films like Dodge City and The Sea Hawk, by confessing “general ignorance,” that the field of music was better left to other, more qualified writers. Hogan covers the impact of the cinematographer, the director, the art director, certainly the actor. Why omit the contribution of the film composer? Does a writer cover his subject, or doesn’t he? ——

This failing aside, Film Noir FAQ remains an excellent introduction to the genre for the novice, and a source of what will be much fresh information to many a connoisseur. Included are some seventy-five stills and posters.

Hogan rightfully concentrates on the noirs of the ’40s and ’50s, with a nod to those of the ’30s. “The classic era of film noir,” he writes, “ends with Psycho (1960).” His afterword of only ten pages briefly summarizes, dismissing as “superfluous,” the post-1960s films, what he calls—what is—neo-noir. As he had written in the previous chapter, “After Psycho, traditional noir had nowhere left to go. The genre had been exploded. After 1960, filmmakers who wanted to recreate noir looked to pictures made before Psycho, because that was where noir tradition lay.”