“With Jaglom, he seemed to find a comfort zone that enabled him to show his vulnerabilities. . . . There was no topic too insignificant or esoteric for Welles to weigh in on.”—— from Peter Biskind’s introduction to the book

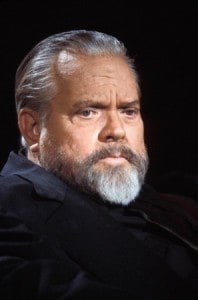

Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water, or, in this case, when you thought the last [intlink id=”150″ type=”category”]Orson Welles[/intlink] archival secrets had been revealed, there seems to have been, stashed away in a shoebox for thirty years, some forty tapes, recorded conversations between British author/director Henry Jaglom and that director of Citizen Kane. Welles’ thoughts—both profound and silly, urbane and vindictive, pompous and contrite, wise and ridiculous—were recorded from 1983 until October of 1985.

If Winston Churchill’s famous axiom about Russia should ever be applied to a person, it could suit no one more aply than the elusive complexity that was Orson Welles: “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” Even these revelations, most of them mild and not unexpected, are merely part of the flow that will continue—more deductions, conjectures and assumptions about this man. As Peter Biskind wrote in his twenty-six-page introduction, Welles was, all in one, “the brilliant child prodigy, the precedent-shattering stage director, the iconoclastic radio figure, the celebrated Shakespearean artist, the ground-breaking filmmaker credited by almost everyone with having made the greatest movie of all time . . . ”

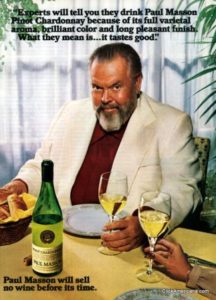

There is, on the other hand, as Biskind also points out, the quite different “TV talk show buffoon, the corny wine commercial huckster, the willing participant in tasteless low-comedy ‘roasts,’ the bloated, seemingly self-destructive outcast whose finished works and aborted projects became legendary . . . ”

There is, on the other hand, as Biskind also points out, the quite different “TV talk show buffoon, the corny wine commercial huckster, the willing participant in tasteless low-comedy ‘roasts,’ the bloated, seemingly self-destructive outcast whose finished works and aborted projects became legendary . . . ”

And it is these diametric extremes between intelligence and buffoonery that set the general tone of Welles’ conversations with Jaglom.

I remember those Dean Martin roasts—“low-comedy” indeed they were, but in a moment of critical frailty, perhaps, I enjoyed them!—and recall, too, Welles’ recurring sessions on Merv Griffin’s talk show. In fact, it was a few hours after a Griffin interview that the star died, of a heart attack. As Biskind writes, “with a typewriter on his lap, working on a script.”

After a thumbnail sketch on Welles in his introduction, Biskind relates how Jaglom met Welles and how the recordings began. In 1978, the two men were having lunch at least once a week at the actor’s favorite haunt, Ma Maison in West Hollywood, opened in 1975 by the French restaurateur Patrick Terrail. Welles agreed to the taping, only if the recorder was unseen, concealed in a bag. On occasions, because of the bag, some of the words are muffled, even inaudible. Biskind has “taken occasional liberties” to make the text more succinct and lucid. The book of conversations is generally in chronological order, but related topics are grouped together.

Ironically, Terrail would relinquish ownership of Ma Maison a month after Welles’ death.

To somewhat set the tone of the conversations to come, Biskind relates that Terrail was kind of a courier for people who wanted to contact Welles. Terrail relayed to the Big Man, which he was—the size of a baby elephant, as Biskind describes him—that George Stevens, Jr. wondered if the director would accept a Kennedy Center award, that the Center would fly him to Washington. “No,” Welles replied. “I would have to sit next to Reagan in the box up there.”

To somewhat set the tone of the conversations to come, Biskind relates that Terrail was kind of a courier for people who wanted to contact Welles. Terrail relayed to the Big Man, which he was—the size of a baby elephant, as Biskind describes him—that George Stevens, Jr. wondered if the director would accept a Kennedy Center award, that the Center would fly him to Washington. “No,” Welles replied. “I would have to sit next to Reagan in the box up there.”

Similarly, once when the archbishop of the Greek Orthodox Church came by the table and invited Welles to high mass at the Cathedral of Saint Sophia and offered to dedicate the service to him, Welles replied, “I am flattered by the invitation, but I must decline. I’m an atheist.”

Each of the twenty-seven chapters is headed with a boldfaced Wellesian quote contained in the text and, below it, a three- or four-line summary of the topics discussed. In the general order of the book, the following are a few of Orson Welles’ comments—and one of Jaglom’s that seemed humorous enough to include: