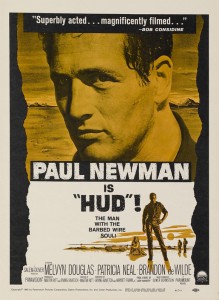

The man with the barbed wire soul!

“You don’t care about people, Hud,” Homer Bannon tells his son. “Oh, you got all that charm goin’ for ya, and it makes the youngsters want to be like ya. That’s the shame of it, because you don’t value nothin’. You don’t respect nothin’. You keep no check on your appetites at all. You live just for yourself. And that makes you not fit to live with.”

What more needs be said? Homer (Melvyn Douglas) accurately summed up the character of his son, Hud (Paul Newman). Homer is right. Hud doesn’t care about people, he hates them. He is a miserable creature from without and from within: from the outside, from what others, besides his father, can see, he is callous in the extreme, a drunk and a womanizer, irreverent, amoral; and from the inside, in that gut awareness of self each of us has, for however long the subconscious can rationalize or suppress it, Hud must be—has to be—filled with an incendiary self-loathing.

Martin Ritt, who directed Hud in 1963, also directed Newman in Hombre, The Long Hot Summer, Paris Blues, The Outrage and Hemingway’s Adventures of a Young Man. As evident by some of these titles, the actor devoted much of his career to playing losers, hustlers, gigolos and general down-and-outers. There are other such films: From the Terrace, The Sting, The Hustler, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Cool Hand Luke, Sweet Bird of Youth and The Left-Handed Gun, among others.

Hud is a downer, no doubt about it, one of the darkest movies imaginable without a killing; there is one natural death. In some inexplicable way, however unattractive his character, Newman makes the film watchable, perhaps because the actor is so good at doing what he does. His introduction is withheld a bit—and then unmistakably in full character, teetering half drunk out of some married woman’s house, and confronted by his nephew’s news that he’s needed at the ranch, and by the arrival of the unseen woman’s husband.

Newman’s method-style acting here is not as obvious, nor as detrimental, as in some of his work. Much as he does to “get in the mood,” before shooting began on Hud Newman briefly lived on a cattle ranch and mastered a cowboy’s walk. Understanding the elusive acting craft—and in some hands the acting art—is well illustrated in Roger Ebert’s comparison of the acting abilities of Paul Henreid and Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca and concluding emphatically, “It’s just that Bogart is so good,” without comprehending how he does it, why some actors have that something extra and some don’t. Why some will never have it.

Newman’s method-style acting here is not as obvious, nor as detrimental, as in some of his work. Much as he does to “get in the mood,” before shooting began on Hud Newman briefly lived on a cattle ranch and mastered a cowboy’s walk. Understanding the elusive acting craft—and in some hands the acting art—is well illustrated in Roger Ebert’s comparison of the acting abilities of Paul Henreid and Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca and concluding emphatically, “It’s just that Bogart is so good,” without comprehending how he does it, why some actors have that something extra and some don’t. Why some will never have it.

The partial offsetting of that miasma which accompanies Hud wherever he goes—the gloom and doom never fully lifts—is due largely to the sincere performances of the other three major stars, and the decency of their characters. Two of the three who live with Hud at the ranch in the film’s beginning know what he is but treat him as an equal, or at least tolerate him for their own sanity and well-being.

Douglas, so good he won a deserved Best Supporting Actor Oscar, is Homer, the upstanding cattle rancher who must witness the destruction of his herd because of hoof-and-mouth disease. Hud, true to form, suggests that his over-principled father keep quiet and sell the tainted beef. What if there’s an epidemic, he says. Everything is fixed, everyone has been bought. The driving of the herd into a bulldozed pit and their slaughter by white-coated government health officials is one of the most horrifying moments in the movie.

Another Oscar winner, for Best Actress, is Patricia Neal, who plays Alma, the Bannon housekeeper and cook. She is fascinated by and drawn to Hud, scoundrel though she knows him to be. “You look pretty good without your shirt on, you know,” she tells him as she waits for a bus. “The sight of that through the kitchen window made me put down my dishtowel more than once.” He had tried to rape her one night in her cabin behind the main house, and she knows she must leave.

Another Oscar winner, for Best Actress, is Patricia Neal, who plays Alma, the Bannon housekeeper and cook. She is fascinated by and drawn to Hud, scoundrel though she knows him to be. “You look pretty good without your shirt on, you know,” she tells him as she waits for a bus. “The sight of that through the kitchen window made me put down my dishtowel more than once.” He had tried to rape her one night in her cabin behind the main house, and she knows she must leave.

Brandon de Wilde, who unfortunately died in a traffic accident in 1972 at age thirty, plays young “Lonnie” Bannon. Lon is at first quite impressed by the “macho” Hud, who shows his nephew the ropes of his tawdry life, with a woman on one arm and a beer in the other hand. As a bystander to Hud’s drunkenness and womanizing, the youngster soon becomes aware he doesn’t want to be like him.

By film’s end, in one way or another, almost as if he wants it that way, Hud has chased everybody away; he has the ranch to himself, alone to be sure and undoubtedly lonely as well. Alma, of course, had to leave; she would have been in peril to remain, though, at the same time, she honestly admits that “it” would have sooner or later happened between them.

And Homer? One night, out looking over his land, he falls off his horse and is found alongside a dirt road by Hud and Lon—in separate vehicles. Hud was having a little sadistic “fun,” ramming the back of Lon’s pickup with his big old Cadillac convertible. When Lon swerves to miss his grandfather, Hud smashes into the truck.

And Homer? One night, out looking over his land, he falls off his horse and is found alongside a dirt road by Hud and Lon—in separate vehicles. Hud was having a little sadistic “fun,” ramming the back of Lon’s pickup with his big old Cadillac convertible. When Lon swerves to miss his grandfather, Hud smashes into the truck.