“Wouldn’t the position of a husband to a defenseless young girl with a large fortune suit him to perfection? . . . Suspicion? It’s a diagnosis.” —Austin Sloper to Lavinia Penniman

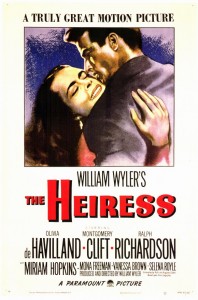

The salient facts about 1949’s The Heiress are pretty well known—that Olivia de Havilland selected director William Wyler as the man for the job, that Montgomery Clift had a low regard for de Havilland as an actress, that Sir Ralph Richardson was most aggressive in stealing scenes and that composer Aaron Copland wanted his name removed from the credits. In spite of the negatives, the film is beautifully crafted, a total enjoyment in all aspects and from all perspectives.

Just as the plot for Henry James’ 1880 novella Washington Square came secondhand from a close friend, so Olivia was encouraged by a friend to travel to New York and see its translation into a Broadway play. At intermission, an enthusiastic Olivia phoned Wyler, suggesting he come to New York to see the play, that he should direct a movie version and that she would star in it. He made the trip, agreed the play would make a great film and, by all means, that de Havilland was meant for the title character.

As I am so often surprised by great Hollywood studio system films that emerge long after that method of making movies has passed, well, after the last viewing, I am surprised again. No, only figuratively “surprised,” as I have known The Heiress most of my life, and, in fact, list it among my Top Ten favorite films.

The plot is straightforward simplicity itself. A plain, inarticulate and reclusive heiress, Catherine Sloper (de Havilland), is pursued by a handsome, jobless adventurer, Morris Townsend (Clift). Her father, Austin (Richardson), a physician who unfavorably compares her with his late beautiful wife, is almost immediately suspicious of the suitor’s motives. He even consults the man’s wise sister (Betty Linley, quite effective in her one-scene appearance in the only film she ever made). Once informed of Austin’s suspicions, she cannot assuage the father’s distrust, but warns him, “If you expect so much of people, you’ll always be disappointed.”

The plot is straightforward simplicity itself. A plain, inarticulate and reclusive heiress, Catherine Sloper (de Havilland), is pursued by a handsome, jobless adventurer, Morris Townsend (Clift). Her father, Austin (Richardson), a physician who unfavorably compares her with his late beautiful wife, is almost immediately suspicious of the suitor’s motives. He even consults the man’s wise sister (Betty Linley, quite effective in her one-scene appearance in the only film she ever made). Once informed of Austin’s suspicions, she cannot assuage the father’s distrust, but warns him, “If you expect so much of people, you’ll always be disappointed.”

When Townsend learns that Catherine’s father threatens to reduce her inheritance by two thirds if she marries him, the young man fails to appear the night they are to elope. Already ill upon return from a European vacation intended to make his daughter forget Morris, Austin announces that his illness is terminal but that he wishes the household to act as though he will recover. In the same scene, the father, unaware of the failed engagement, inquires if Catherine is keeping secret the time of her departure with Townsend. She announces she will not be leaving, that he had deserted her.

It is now, in one of the best scenes in the film, although there are many such “best” scenes, long stretches of superb dialogue, that the girl, once inarticulate and without her mother’s poise and seemingly with little mind of her own, verbally attacks her father.

It is now, in one of the best scenes in the film, although there are many such “best” scenes, long stretches of superb dialogue, that the girl, once inarticulate and without her mother’s poise and seemingly with little mind of her own, verbally attacks her father.

“Don’t be kind to me. It doesn’t become you. . . . You have cheated me. You thought that any handsome, clever man would be as bored with me as you were. . . . I lived with you for twenty years before I found out you didn’t love me. I don’t know that Morris would have hurt me or starved me for affection more than you did. Since you couldn’t love me, you should have let someone else try.”

Then Copland’s score, heretofore silent, provides a dramatic period, a two-note punch, like two nails in a coffin as it were, a motif reminiscent of the composer’s “A Lincoln Portrait.”

Austin mutters, “You have found a tongue at last, Catherine . . . ”

After her father’s death, Catherine settles into a life of spinsterhood. It’s soon apparent, with of course an appropriate time lapse, that she has matured, grown more assured and, yes, become actually attractive. Even the thin, mousy voice, perhaps overly exaggerated when she girlishly told her father of her engagement, has gained an unexpected resonance.

One evening while out on the town, Lavinia has found Townsend and has brought him to the house. He awaits outside the front door. Lavinia, who has always succumbed to Townsend’s charms and entertained him in the Sloper home while Catherine and Austin were away in Europe, pleads his case. An adamant Catherine instructs that the door be bolted. Then, as she hears his voice from the doorway and feels a flood of memories, her face softens, she relents and allows his entry. Once again she seems charmed by what he says, even agreeing to marry him, even leaving the room to fetch a wedding present for him. For the viewer waiting for a sign of Townsend’s sincerity, while he is left alone, he saunters through the room and into the next one, admiring their elaborate Victorian furnishings—and smiling. Catherine returns with a set of ruby buttons for him. It seems she has been taken in—again.

One evening while out on the town, Lavinia has found Townsend and has brought him to the house. He awaits outside the front door. Lavinia, who has always succumbed to Townsend’s charms and entertained him in the Sloper home while Catherine and Austin were away in Europe, pleads his case. An adamant Catherine instructs that the door be bolted. Then, as she hears his voice from the doorway and feels a flood of memories, her face softens, she relents and allows his entry. Once again she seems charmed by what he says, even agreeing to marry him, even leaving the room to fetch a wedding present for him. For the viewer waiting for a sign of Townsend’s sincerity, while he is left alone, he saunters through the room and into the next one, admiring their elaborate Victorian furnishings—and smiling. Catherine returns with a set of ruby buttons for him. It seems she has been taken in—again.

Or has she? She suggests he pack his things and return for her—for that long-missed elopement. As soon as Townsend disappears out the door, Copland, in the telegraphing manner that has always been a sin of many film scores, jabs the screen with a stinger chord, cold and sinister. Now, perhaps, the viewer knows where she stands! To Lavinia, who re-enters and urges her to hurry, Catherine coldly observes, “He came back with the same lies, the same silly phrases. . . . He’s grown greedier with the years. The first time, he only wanted my money, now he wants my love, too. Well, he came to the wrong house—and he came twice. I shall see that he never comes a third time.”