“There must still be horse sense in the British people, so he’ll make a direct appeal. How? By radio. He pleads, he warns, he threatens. Every night his mellifluous voice is heard, and step by step he’s become the lowest of all men—the traitor.” — Mike Latimer

Mike Latimer has heard the voice before. It’s so familiar. In the reverberating acoustic of a hallway, Mike overhears this man talking, and, now unable to see him, he remembers—and knows who he is! Certainly not this Browne fellow he professes to be. Mike’s newly acquired girl friend, Katie, is with this enigmatic fellow, when Mike emerges to confront Browne, who is really . . . No, that would spoil the film if you haven’t seen it. And it’s a fun movie to follow, from beginning to end.

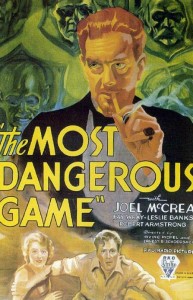

Run for the Sun is at least the second filmed version of Richard Connell’s 1924 short story The Most Dangerous Game, about a deranged count who lives on an isolated island and hunts humans as the most challenging game of all. The story was first filmed in 1932 by RKO under that title, starring Joel McCrea, Fay Wray, Leslie Banks and Robert Armstrong. Although there have since been other film and TV adaptations of the basic plot, the next Hollywood version—and worst of the three under discussion—came in 1946, A Game of Death with John Loder, Audrey Long, even Jason Robards, Sr. Surprisingly, to be so poor a film, it was directed by Robert Wise, who had just done the Boris Karloff version of The Body Snatchers. Who knows?!

Run for the Sun is at least the second filmed version of Richard Connell’s 1924 short story The Most Dangerous Game, about a deranged count who lives on an isolated island and hunts humans as the most challenging game of all. The story was first filmed in 1932 by RKO under that title, starring Joel McCrea, Fay Wray, Leslie Banks and Robert Armstrong. Although there have since been other film and TV adaptations of the basic plot, the next Hollywood version—and worst of the three under discussion—came in 1946, A Game of Death with John Loder, Audrey Long, even Jason Robards, Sr. Surprisingly, to be so poor a film, it was directed by Robert Wise, who had just done the Boris Karloff version of The Body Snatchers. Who knows?!

While The Most Dangerous Game is somewhat dated, tacky in its sets and melodramatically acted by Leslie Banks as the count—Fay Wray was never lovelier—Run for the Sun is well done in all respects. The plot is expanded, the character development more in-depth, the romantic elements more mature, though sometimes a bit soap operaish and predictable. Considerable humor is added and the action—the escape from Browne’s hacienda through the jungle—is much more exciting, grippingly longer without seeming so.

Jane Greer, in my opinion, has always been an underrated actress. Richard Widmark, who throughout his career seemed cast as either criminals or cowboys, plays, rather convincingly, the stalled writer, one of his best roles. Trevor Howard, who had made, certainly, two special films, Brief Encounter in 1945 and The Third Man in 1949, is Browne. Peter van Eyck as his friend, the so-called “scientist” Dr. Van Anders, was typecast from the beginning, and in his first film Hitler’s Children, as the proverbial Nazi.

Jane Greer, in my opinion, has always been an underrated actress. Richard Widmark, who throughout his career seemed cast as either criminals or cowboys, plays, rather convincingly, the stalled writer, one of his best roles. Trevor Howard, who had made, certainly, two special films, Brief Encounter in 1945 and The Third Man in 1949, is Browne. Peter van Eyck as his friend, the so-called “scientist” Dr. Van Anders, was typecast from the beginning, and in his first film Hitler’s Children, as the proverbial Nazi.

Instead of following the shipwrecked male lead on that island as in the McCrea version, this story begins with magazine writer Katie Connors (Jane Greer) arriving in San Marcos in search of an interview with the self-exiled, rumored-to-be-written-out adventure author, Mike Latimer (Richard Widmark). A possible suspenseful delaying of Latimer’s first appearance is disregarded in favor of an immediate encounter, though Katie fails in her attempts to “nonchalantly” meet him. He does give her a quick once-over in passing on the boat dock when he returns from a fishing trip, and later, when she conveniently drops one of his books as he walks by, he hands it to her and walks on.

It’s only when the Mexican waiter, not understanding how she wants her drink prepared, brings over Latimer to translate that the aloof writer decides to play her game, cynically deducing her chic clothes and preppy education, even her pricey perfume. She doesn’t, of course, tell him her purpose, posing instead as a tourist waiting for nonexistent friends to arrive for a fishing trip. Fishing which, by the way, she doesn’t enjoy.

Previously, while sitting in the bar alone, she takes from her purse a magnetic note pad to record an observation, laying on the table the metal pen, which immediately snaps against the pad. Not a casual insert shot, as—pay attention—it will influence the plot later.

Katie and Mike get to know one another in typical Hollywood vignettes—deep sea fishing (did she and Mike bring in that marlin or not?) and riding donkeys, though the usual cliché for such imagery, lovers-to-be frolicking in a springtime field, is wisely avoided here. In a casual walk together, Mike produces from his pocket a lone bullet and details how he acquired it—on D-Day, from a German’s jammed rifle. Keeping a bullet “with his name on it,” he says, will protect him. Even half asleep viewers will assume that the bullet will be of crucial importance later.

Katie and Mike get to know one another in typical Hollywood vignettes—deep sea fishing (did she and Mike bring in that marlin or not?) and riding donkeys, though the usual cliché for such imagery, lovers-to-be frolicking in a springtime field, is wisely avoided here. In a casual walk together, Mike produces from his pocket a lone bullet and details how he acquired it—on D-Day, from a German’s jammed rifle. Keeping a bullet “with his name on it,” he says, will protect him. Even half asleep viewers will assume that the bullet will be of crucial importance later.

In answering a phone call from New York, Katie confides to her editor that maybe she isn’t the right person for this assignment after all. See, she’s obviously drawn to Mike and feels guilty in deceiving him, especially in the next scene when he confides his current writer’s block is caused by the trauma of an adulterous wife. “You’re a good girl, Katie,” he tells her. “I trust you.” A little bit over the top, that soap opera stigma. His confession makes her feel even more guilty, so——