“So you see, the whole thing has been as inevitable as the nursery rhyme. When the boat arrives from the mainland, there will be ten dead bodies, and a riddle no one can solve on Indian Island.” — the judge

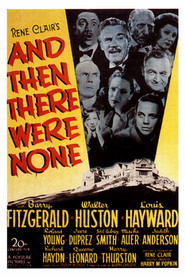

“None,” you say? There have been four—four movie versions, that is, of Agatha Christie’s Ten Little Indians, a mystery novel published in 1939 and first filmed as And Then There Were None in 1945. These titles are among three alternates, as Agatha tended to provide at least two titles for each of her mysteries. If there’s ever an indictment against the logic of movie remakes, the series of repetitions that followed take the cake, over and over, of how recycled movies so often become worse and worse.

Beyond any doubt, And Then There Were None is the high-flier, the top of the heap, the unsinkable ship of the group, if ever there was one. And “unsinkable ship” isn’t entirely inappropriate, as eight individuals are delivered to a small island off the Devon coast in a motorboat; the butler and cook, completing the ten little “Indians,” are already there when the main party arrives.

By now, through various rip-offs, the plot is a familiar one. Ten people are invited by a Mr. U. N. Owen to spend the weekend on Indian Island. As the newly arrived guests are standing around nervously, one alludes to two Englishmen who were marooned on an island but never spoke to one another—because they hadn’t been introduced. Through a somewhat novel device, most of the individuals look directly into the camera as they introduce themselves: an alcoholic doctor (Walter Huston), a retired judge (Barry Fitzgerald), an adventurer (Louis Hayward), a secretary/the love interest (June Duprez), a private detective (Roland Young), a Russian playboy (Mischa Auer), a spinster (Judith Anderson), an old general (C. Aubrey Smith) and two house servants, the butler (Richard Haydn) and the cook, his wife (Queenie Leonard).

The subsequent remakes, all under the title of Ten Little Indians, were like misguided shadows of the original, each, in turn, becoming progressively more unnecessary. The second, 1966 version, taking place, now, in a remote Alpine chalet, is reasonably watchable, possibly because of lead actor Hugh O’Brian as the adventurer. Taking the rather sexually benign role played by June Duprez as a challenge, Shirley Eaton, a sexpot of the time, becomes a woman “in heat,” in the words of critic Michael Tennenbaum. Among the other roles, Wilfrid Hyde-White is the judge, Dennis Price the doctor, Leo Genn the general and Fabian—any one remember him?—the playboy. Still, compared with the original, everything cast a shadow of ineptitude, terribly unsubtle and disjointed under George Pollock’s direction.

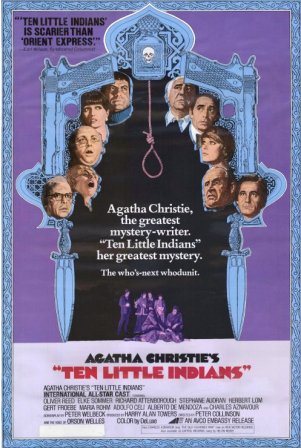

The 1975 version, now set—guess?—at a lonely hotel in the Iranian desert, is painfully weak in all areas and ultimately forgettable, reflecting slack tension and, at the other extreme, a greater emphasis on the sex that had been tantalizingly explored in the previous retelling. The respective roles of adventurer, sexpot, judge, doctor, general and playboy (sorry, no tinker or spy!) are played by Oliver Reed, Elke Sommer, Richard Attenborough, Herbert Lom, Adolfo Celli and Charles Aznavour. Orson Welles’ voice is that of the indicter of the ten.

The 1975 version, now set—guess?—at a lonely hotel in the Iranian desert, is painfully weak in all areas and ultimately forgettable, reflecting slack tension and, at the other extreme, a greater emphasis on the sex that had been tantalizingly explored in the previous retelling. The respective roles of adventurer, sexpot, judge, doctor, general and playboy (sorry, no tinker or spy!) are played by Oliver Reed, Elke Sommer, Richard Attenborough, Herbert Lom, Adolfo Celli and Charles Aznavour. Orson Welles’ voice is that of the indicter of the ten.

Plummeting to the bottom of the heap, achieving BOMB status, the 1989 venture is a disgusting bore. The locale has been moved to Africa and a safari. Huddled around the campsite fire are Frank Stallone as the adventurer, Sarah Maur Thorp as his love interest, Donald Pleasence as the judge, Yehuda Efroni as the doctor, Herbert Lom back for another try, now as the general, and Neil McCarthy as the playboy. This version transports the viewer—in time, not in spirit—back to the 1930s. Perhaps in the Great White Hunter element, the producers and screenwriters attempted to catch some of the magic dust from the definitive movies in that genre—Red Dust, its remake Mogambo or even Gregory Peck’s The Macomber Affair. Far from “catching” anything inspirational, the film is an insult to human intelligence and creativity, a mess that should never have been made. Here is the best possible evidence, then, of the folly of most remakes.

The three versions were British and at least one of the producers on each film was Harry Alan Towers, who had a misguided obsession with remaking Ten Little Indians, with perhaps a secret motive to do them all in; if it was to film the definitive rendering, he failed—miserably.

It’s a strange paradox that the definitive version of this typical, most-often filmed Agatha Christie armchair mystery should be made by an American studio, 20th Century-Fox, though the so-called paradox is somewhat negated: none of the eleven members of the cast are American; they are South African, Australian, Irish, even Russian, but mostly English. Among the actors, the closest to being an American is Walter Huston, who is Canadian.

Not too far removed from Hollywood’s fabled Golden Age, depending upon where the closing parenthesis is drawn, And Then There Were None has those exceptional production values typical of that time—and continues the tone of foreign talent: director René Clair (French), cinematographer Lucian Androit (also French), set director Edward Boyle (Canadian), art director Ernst Fegté (German) and composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (Italian). Not that there aren’t some Americans, film editor Harvey Manger and the Oscar-winning screenwriter Dudley Nichols, for example.

Much of the action takes place on a living room set with wide archways and several glass walls that provide views into other rooms, offering an unclaustrophobic openness. Edward Boyle’s work here is reminiscent of his similar set for Separate Tables, even more extensively done with glass walls and folding glass doors.