“If you think I’m going to stand there and let Dr. Lloyd splash me with water, you’re mistaken!” —— Clarence Day (William Powell)

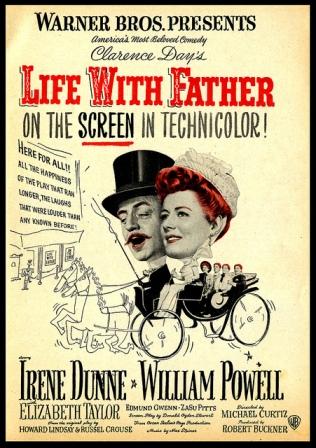

Life with Father, set in the 1880s, in a more leisurely time than ours and one long gone, is a memoir by a longtime bed-ridden Clarence Day about his kind but eccentric father, Clarence “Clare” Day, Sr. The author died in 1935, shortly after the memoir was published. Four years later, Howard Lindsey and Russel Crouse translated the book into a play, still the longest-running non-musical on Broadway, holding the boards for over seven years.

In the year the play closed, 1947, Warner Bros. released the film version, whose success equaled that of the book and play, earning Oscar nominations—unsuccessful as it would prove—for William Powell as Best Actor and Max Steiner for his score, as well as for Best Cinematography and Best Art-Set Decoration.

Set in 1883 in New York City, the movie is a faithful and charming adaptation of Day’s memoir, thanks partly to the close, on-set scrutiny of Day’s widow, Katherine, and to the ideal casting. Powell is Clare Day, the businessman who organizes his Madison Avenue household like his business. He keeps the cook Margaret (Emma Dunn) hopping, with a “call signal” of two heavy foot stamps on the floor that shakes the chandeliers. He so terrorizes the maids that four come and go during the short time period of the film.

His wife Vinnie, played by Irene Dunne, who resented, she said, her part as a “rattle-brain” wife, has, hidden beneath the façade of an apparently subservient Victorian wife, a strong will of her own, and she often prevails. Her understanding of finances, however, conflicts with her husband’s strict, practically day-to-day management of the family checkbook. He finds it difficult to comprehend her reasoning, that, if a $15.95 china pug dog is returned in exchange for a $15.95 suit—this reflects an 1883 price, remember!—then the Days must owe nothing. On another occasion, repulsed by a china pug dog his wife has bought, Clare asks, “What did you pay for it?” “I didn’t pay anything,” she replies. “I charged it.”

His wife Vinnie, played by Irene Dunne, who resented, she said, her part as a “rattle-brain” wife, has, hidden beneath the façade of an apparently subservient Victorian wife, a strong will of her own, and she often prevails. Her understanding of finances, however, conflicts with her husband’s strict, practically day-to-day management of the family checkbook. He finds it difficult to comprehend her reasoning, that, if a $15.95 china pug dog is returned in exchange for a $15.95 suit—this reflects an 1883 price, remember!—then the Days must owe nothing. On another occasion, repulsed by a china pug dog his wife has bought, Clare asks, “What did you pay for it?” “I didn’t pay anything,” she replies. “I charged it.”

Then, to keep things lively, the eldest of four sons, Clarence, Jr. (Jimmy Lydon), who is going to Yale next year, has an air of superiority. When he wears an altered suit of his father’s, he assumes his personality, inheriting a reluctance to kneel during the Episcopal services. When a young lady, Mary Skinner (Elizabeth Taylor in her seventh film role), comes for a visit, and toward whom he becomes instantly enamored, he insists she write him first after she leaves. “You’ll write me first,” he instructs, with overtones of his father, “and you’ll do it right away, the first day!” Even that she is a Methodist causes some momentary anxiety.

And later, when the paternal metamorphosis threatens his budding love life and he expresses his father’s signature cry of disapproval at double forte volume, “Oh, gad!,” he knows it’s time to demand a suit of his own.

And later, when the paternal metamorphosis threatens his budding love life and he expresses his father’s signature cry of disapproval at double forte volume, “Oh, gad!,” he knows it’s time to demand a suit of his own.

Throughout the film, Clarence, Jr. takes center stage over his three brothers, all who have red hair, like their parents. Next in age is John (Martin Milner), the family’s aspiring scientist and entrepreneur. He first invents a burglar alarm that prompts a “stop that noise, stop it, I say!” from father, and, second, promotes, with Clarence, Jr., a snake oil elixir that cures all diseases but worsens his mother’s illness when he sneaks some into her tea.

The third brother is Whitney (Johnny Calkins), who is struggling to learn his catechism for an upcoming confirmation. Fourth is Harlan (Derek Scott), whose biggest concern, even beyond his dog, is missing his unbaptized father when he arrives in heaven.

The nostalgic atmosphere of the main title conjures up the 1880s, with photos from the period, viewed through a hand-held stereoscope. Then the last photo, an old still of a New York street, segues into a live street in 1883. A policeman on his beat approaches a servant on her knees scrubbing the steps of the Day brownstone.

The nostalgic atmosphere of the main title conjures up the 1880s, with photos from the period, viewed through a hand-held stereoscope. Then the last photo, an old still of a New York street, segues into a live street in 1883. A policeman on his beat approaches a servant on her knees scrubbing the steps of the Day brownstone.

“Well,” he says, “these are certainly the cleanest steps on Madison Avenue.”

“That’s how Mr. Day wants them kept,” the servant replies. Moments later, a first-day-on-the-job maid, Annie (Heather Wilde), emerges from the lower kitchen entrance to obtain Mr. Day’s milk can from a horse drawn milk wagon.

As might be expected from director Michael Curtiz, Clare’s introduction at breakfast that morning is a dramatic one—first, only a shouted “Oh, gad!”—then his shadow (a Curtiz trademark) on an upstairs wall while he complains about a lost tie. “I don’t know what this world’s coming to,” he complains. That cry will be heard again. And, last, in a close-up, his feet descend the stairs, and he becomes almost like an arriving sovereign as he greets his family in the dining room.

As might be expected from director Michael Curtiz, Clare’s introduction at breakfast that morning is a dramatic one—first, only a shouted “Oh, gad!”—then his shadow (a Curtiz trademark) on an upstairs wall while he complains about a lost tie. “I don’t know what this world’s coming to,” he complains. That cry will be heard again. And, last, in a close-up, his feet descend the stairs, and he becomes almost like an arriving sovereign as he greets his family in the dining room.

From her husband, who doesn’t like visitors, family or otherwise, in the house, Vinnie has kept a secret, that guests are coming: Vinnie’s cousin, Cora Cartwright (Zasu Pitts), and her young friend Mary. Further, Vinnie has promised them that Clare will take them all to Delmonico’s.

Another guest who drops in occasionally, depending upon the current circumstance or crisis, is Reverend Dr. Lloyd (Edmund Gwenn, recipient of the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his Kris Kringle in Miracle on 34th Street, made the same year by 20th Century-Fox). On an early occasion, he responds to the startling news that Clare has never been baptized, and even sermonizes from the pulpit on the essential ritual. Even Clare himself has just remembered the fact and announces it at a family meal, unaware of the consternation it will cause everyone.

Another guest who drops in occasionally, depending upon the current circumstance or crisis, is Reverend Dr. Lloyd (Edmund Gwenn, recipient of the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his Kris Kringle in Miracle on 34th Street, made the same year by 20th Century-Fox). On an early occasion, he responds to the startling news that Clare has never been baptized, and even sermonizes from the pulpit on the essential ritual. Even Clare himself has just remembered the fact and announces it at a family meal, unaware of the consternation it will cause everyone.

On a later occasion, Reverend Lloyd arrives to console the family on Vinnie’s serious illness. When his wife seems near death, Clare offers a cautionary prayer, that if she recovers he will become baptized. It means a lot to her, since, as she once told Cora, “I just couldn’t go to heaven without Clare. Why, I get lonesome for him even when I go to Ohio.”

In the end, when Vinnie recovers and Clare reneges on his promise, Vinnie arranges for a surprise ceremony at a church in Audubon Park. Again Clare is adamantly against it. The next time Clare becomes disgusted, now over that ceramic pug dog Vinnie has bought and says he won’t become baptized as long as that object remains in the house, Vinnie seizes upon another plan.

She sends Clarence, Jr. to the department store to exchange the pug dog for a new suit for himself. Next morning, when Cora and Mary drop in for another visit, the young man makes up with Mary, now that he is less imperious in his own suit and has become his own man.

She sends Clarence, Jr. to the department store to exchange the pug dog for a new suit for himself. Next morning, when Cora and Mary drop in for another visit, the young man makes up with Mary, now that he is less imperious in his own suit and has become his own man.

With the pug dog gone and Clare’s latest promise supposedly in effect, Vinnie orders an expensive taxi to take everyone to Audubon Park. Knowing that the charges mount for even an idle taxi, Clare orders an immediate, no-delay departure for the church and, finally, his baptism.

While Irene Dunne contributes charm, wit and patience but also quiet determination to Life with Father, William Powell remains the unavoidable center. Some Hollywood stars specialize in their versatility, for better or worse sometimes, while others, like Powell, settle into a comfortable degree of typecasting. Although he has made other types of films, he seems especially suited to the drawing room. There he is either the debonair detective, whether the famous Thin Man or Philo Vance, or the suave lover to such ladies as Jean Harlow, Mary Astor, Carole Lombard and, of course, Myrna Loy (fourteen films together, including six in the Thin Man series).

Warner Bros.’ hardest working, most versatile house director, Michael Curtiz always adjusts easily to innumerable changes in genres. From Westerns (Dodge City, 1939) to Oscar-winning musicals (Yankee Doodle Dandy, 1942) to melodramas (Mildred Pierce, 1945) to swashbucklers (The Adventures of Robin Hood, 1938) to film noirs (Angels with Dirty Faces, 1938), he now, with Life with Father, returns to comedy (We’re No Angels, 1955).

Warner Bros.’ hardest working, most versatile house director, Michael Curtiz always adjusts easily to innumerable changes in genres. From Westerns (Dodge City, 1939) to Oscar-winning musicals (Yankee Doodle Dandy, 1942) to melodramas (Mildred Pierce, 1945) to swashbucklers (The Adventures of Robin Hood, 1938) to film noirs (Angels with Dirty Faces, 1938), he now, with Life with Father, returns to comedy (We’re No Angels, 1955).

Curtiz’ straightforward direction avoids any hint of sentimentality, and Donald Ogden Stewart’s faithful screenplay emphasizes the humor of both the memoir and the play. The combined fluid cinematography of J. Peverell Marley (The House of Wax, 1953, and The Spirit of St. Louis, 1957) and William V. Skall (Rope and Joan of Arc, both 1948) would seem to only accentuate the leisurely pace of things, but the plot moves at a laugh-filled clip, thanks mainly to these contributors and to the warm sincerity and enthusiasm of the players.

Along with the heavy Victorian interiors, Max Steiner’s score, and all the period music he includes, adds to the 1880s flavor. The composer’s own tune in the main title, heard frequently throughout, ideally portrays “both the pomposity of the character and the good-heartedness” of Clarence Day—the words of Tony Thomas in his indispensable book, Music for the Movies.

Most of the popular tunes, however, were written after the 1883 time of the film, including “Sweet Marie,” which Dunne and Powell sing, and “Love’s Old Sweet Song,” which Powell sings as he plays the piano. Even another piece of source music, the “Treasure Waltz” from Johann Strauss, Jr.’s Gypsy Baron, heard at Delmonico’s, was premiered in late 1885.

Most of the popular tunes, however, were written after the 1883 time of the film, including “Sweet Marie,” which Dunne and Powell sing, and “Love’s Old Sweet Song,” which Powell sings as he plays the piano. Even another piece of source music, the “Treasure Waltz” from Johann Strauss, Jr.’s Gypsy Baron, heard at Delmonico’s, was premiered in late 1885.

Life with Father, without the least bit of strain it seems, provides a joyous, funny and heartwarming movie experience. For those viewers accustomed to a faster pace and all that entails—the quick cutting, the endless close-ups, the loud noises—some adjustments may have to be made. But here is a quiet oasis, a return, if only momentarily, if only on film, to a more leisure era when there was time for thought and personal reflection, and even, dare it be suggested, introspection.