“Sawyer, you’re going out a youngster, but you’ve got to come back a star!” —Warner Baxter to Ruby Keeler

The advent of sound brought to the movie-going public of the ’30s, first and foremost, the musical. Why the musical instead of gangsters, mysteries, swashbucklers or straight dramas? Because music was the obvious best demonstration of the new novelty and the easiest kind of film to make: just parade singers and dancers before what was, in those earliest days, a largely stationary camera in a box.

Warner Brothers’ latest release, a box-set of twenty tuneful movies made between 1927 and 1988, is a superb testimony to the popularity of the filmed musical through the decades. Even now, in 2013, the musical is alive and well in Tom Hooper’s Les Miserables.

But by 1933 the Hollywood musical seemed to have over-stayed its welcome—already, after only seven years of sound! The public was tired of the rigid camera, the often second-rate songs, the unimaginative staging and trite, ever-repeated story lines—backstage intrigue and rags-to-riches ingénues.

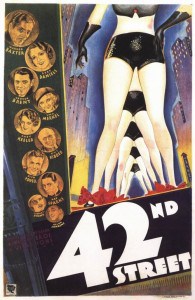

The first sound picture, The Jazz Singer, was, just by coincidence, a musical, and the studio that made it, Warner Brothers, also produced 42nd Street, in 1933. Besides saving WB from bankruptcy, the film was a milestone, some say the first real, full-fledged Hollywood musical, period. Musicals were back in favor, and they followed in the late ’30s with gusto, including those of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

The success of 42nd Street was due to a number of creative minds, primarily a director, Lloyd Bacon, called by Leslie Halliwell “competent rather than brilliant”—well, maybe “brilliant” this time!—and a master of song and dance, Busby Berkeley, who was always brilliant. Oh, Berkeley’s shows were nothing more than girlie shows. Remember the pyramids of scantily clad young ladies, or the camera moving between gals’ straddled legs, or these beauties coming down an endless staircase, or aquatic ballet around a water fountain? Most of which are in 42nd Street.

And the music! Yes, this music that helped, somehow, to soften the Great Depression. Harry Warren’s tunes and Al Dubin’s lyrics had a “little” something to do with the success then, and the reputation now, of 42nd Street. Among the best-remembered songs are “Forty-Second Street,” “You’re Getting to Be a Habit with Me” and “Shuffle Off to Buffalo.”

And the music! Yes, this music that helped, somehow, to soften the Great Depression. Harry Warren’s tunes and Al Dubin’s lyrics had a “little” something to do with the success then, and the reputation now, of 42nd Street. Among the best-remembered songs are “Forty-Second Street,” “You’re Getting to Be a Habit with Me” and “Shuffle Off to Buffalo.”

Interestingly, the lyrics in the latter, that include “panties” and “scanties,” were a-okay in 1933. True, the Production Code had been adopted in 1930, but not enforced until 1934. The Code was seriously “compromised” in 1953 with The Moon Is Blue and in 1959 with Anatomy of a Murder when “panties” was mentioned—several times.