“Amazing, Holmes!” “Elementary, Watson.”

In two films in 1939, The Hound of the Baskervilles and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, 20th Century-Fox launched Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce on their Sherlock Holmes odyssey. In both films, the studio had respected the period of the Sir Arthur Conan Doyle stories—the late nineteenth century: hansoms, gas street lamps and frock coats. Adventures, however, with Holmes up against Professor Moriarty’s scheme to steal the crown jewels, was based on William Gillette’s play, Sherlock Holmes. Surprisingly, though incidental to the point, it is the better of the two films.

This disregard for Doyle’s sacred text became the norm when, in 1942, Universal began its own twelve-film Rathbone/Bruce series with Sherlock Homes and the Voice of Terror. The period, from here on, would be changed to the present, then the middle of World War II—motor cars and telephones, though, yes, both appear in the later Doyle stories. In Voice, the main title credits indicate “based on” Doyle’s His Last Bow, but it contains little of the story except for Holmes’ closing words about portents of war—“There’s an east wind coming all the same, such a wind as never blew on England yet,” etc.—the first of the propaganda homilies that would close the early films in the series.

In the next Universal film, Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon, the detective is fighting Moriarty again, now over the integrity of an Allied bomb sight. (Among the fourteen films of the two studios, three different actors would play Holmes’ arch nemesis.) As for “based on,” the only bit used of Doyle’s The Dancing Men is the idea of a cipher, the Doyle stick figures becoming letter transposition in the film.

In the third film, Sherlock Holmes in Washington, from an original screenplay by Bertram Millhauser, the cast plays hide and seek with a piece of microfilm, George Zucco’s villainy called to the fore as the evil Heinrich Hinkle—pseudonym of Heinrich Himmler? Holmes seems out of his element in America, though Watson enthusiastically embraces chewing gum and Sunday comics.

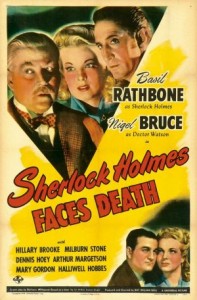

The fourth film, Sherlock Holmes Faces Death (1943), then, is a welcomed advance, more correctly a change in direction, over those first three Universal mysteries. True, the time is the same, but now WWII is only an incidental backdrop, and would disappear entirely in the later films. Most important, the film returns to the atmosphere and spirit of the world the master detective best inhabits, that of fog, eerie mansions, thunderstorms, deep crypts, riddles and egomaniacal murderers. All these ingredients abound in the film, thanks greatly to screenwriter Millhauser and producer/director Roy William Neill, both who have an inborn sense of atmosphere and mystery.

Faces Death, as with The Pearl of Death, comes close to representing the Doyle original, in this case The Musgrave Ritual, a unique adventure wherein Holmes relates to Watson a story in which his friend has no part, with all the inherent quotes within quotes within quotes.

And also, not to be forgotten, is that improvement in Basil Rathbone’s unnatural and curious coiffure in the first three films, when his hair sweeps from behind his head, as if caught in a heavy southerly wind, and emerges along each temple, waves spiked forward like virulent antennae.

And also, not to be forgotten, is that improvement in Basil Rathbone’s unnatural and curious coiffure in the first three films, when his hair sweeps from behind his head, as if caught in a heavy southerly wind, and emerges along each temple, waves spiked forward like virulent antennae.

It is an unusually long time before Holmes (Rathbone) first appears in Sherlock Holmes Faces Death. First, there’s the opening, a visit to a pub, the Rat and Raven. That prerequisite atmosphere is already set. It’s a dark and stormy night, the pub shingle swinging and creaking in the wind. The barmaid (Norma Varden) announces it’s almost quitting time, and one balding, mustachioed gentleman (Harold de Becker, looking like today’s elderly Richard Johnson) informs the curious customers about the strange goings-on at the Musgrave estate, Hurlstone Towers. At the bar is a young Peter Lawford, although he had already appeared in twenty films, usually uncredited, as here.

The Musgraves have turned their estate into a convalescent home for army officers (a basis for one season of ITV/PBS’ current Downtown Abbey), and in charge of their well-being is Dr. John Watson (Bruce). While the wind blows through the windows and a tower clock chimes thirteen—more atmosphere—Brunton the butler (Halliwell Hobbes) updates Watson on the ghosts that inhabit this “grim old pile,” as Watson would later describe the place.

Brunton is known to listen at keyholes, drink too much and write poetry, and, in a moment of intoxication, quote Shakespeare—Henry VIII: “Farewell, a long farewell to all my greatness.”

The viewer is introduced to the Musgrave family: the two brothers, grouchy old Geoffrey (Frederic Worlock) and sly, pipe-smoking Phillip (Gavin Muir) and their sister Sally (Hillary Brooke), who is worried about the health of her suitor, Captain Vickery (Milburn Stone of Gunsmoke fame), one of the recovering officers.

The viewer is introduced to the Musgrave family: the two brothers, grouchy old Geoffrey (Frederic Worlock) and sly, pipe-smoking Phillip (Gavin Muir) and their sister Sally (Hillary Brooke), who is worried about the health of her suitor, Captain Vickery (Milburn Stone of Gunsmoke fame), one of the recovering officers.