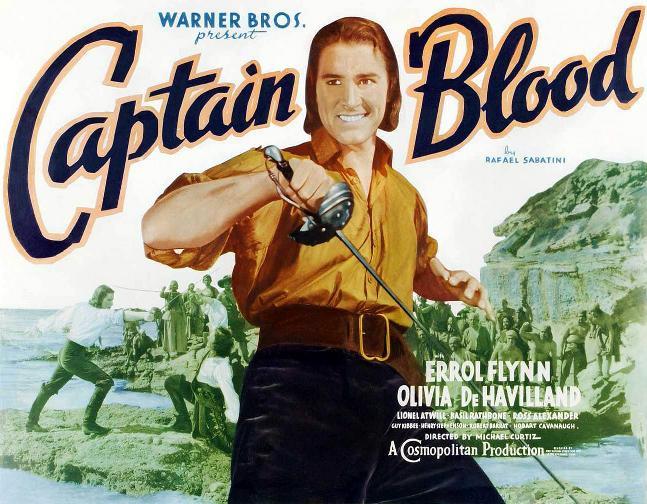

His sword carved his name across the continents – and his glory across the seas!

It’s been so long since Captain Blood was mint fresh, in 1935—seventy-five years ago in 2010, it will be—that its startling and, in some ways, revolutionary place in the history of Hollywood is often underestimated or, worse, overlooked.

True, from our modern perspective, the film has a number of negatives and seems a mite quaint—we are, after all, so sophisticated! Despite the latest restoration on DVD, the physical age of the film shows, and some of the sets and miniatures are, well, tacky. For some viewers, there’s the stigma of the black and white. All that talking could’ve been supplanted by today’s craving for more action. The mono sound is “pinched” and distorted, hardly capable of capturing the proper noise which all “good” films require. And the old-fashioned description frames, reminiscent of the days of the silents, date it as much as anything, though Gone with the Wind has them and manages to be a great film.

In retrospect—and try to sense those times: a rather naïve, depression-era, pre-WWII America—Captain Blood launched at least three careers: Errol Flynn’s, Olivia de Havilland’s and Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s. When Jack Warner and Hal B. Wallis, the savvy executive producer, one of the best in the business, were desperate to replace the originally scheduled title actor, Robert Donat, who became unavailable, they found their contract leading men either busy or wanting in the necessary persona. (Can anyone—well, anyone—imagine, in the title role, George Brent, who was considered?!) Blood was perhaps the most expensive Warner Bros. production of the year, and the Tasmanian actor the bosses finally selected would be a gamble.

In retrospect—and try to sense those times: a rather naïve, depression-era, pre-WWII America—Captain Blood launched at least three careers: Errol Flynn’s, Olivia de Havilland’s and Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s. When Jack Warner and Hal B. Wallis, the savvy executive producer, one of the best in the business, were desperate to replace the originally scheduled title actor, Robert Donat, who became unavailable, they found their contract leading men either busy or wanting in the necessary persona. (Can anyone—well, anyone—imagine, in the title role, George Brent, who was considered?!) Blood was perhaps the most expensive Warner Bros. production of the year, and the Tasmanian actor the bosses finally selected would be a gamble.

Flynn had only moderate acting experience. His roles in the four films he made since 1933 were small and somewhat unimpressive. Who remembers him as Fletcher Christian, for example. But he improved so rapidly in Blood that many early scenes were reshot. In fact, he ends up being quite good on screen, giving the impression of understanding his role, approaching his part, maybe, with the care of a Shakespearean actor. It’s a common appraisal but true: besides being able to flourish a sword better than anyone before or since, Flynn wore period clothes with style, as if he had stepped out of the past, or, as some have said, belonged there. His director, the Hungarian Michael Curtiz—of the fractured English and “bring-on-the-empty-horses” fame—told Flynn to tear some of that sissy lace from his 17th-century clothes, which Flynn did.

He spoke the convoluted lines naturally and with conviction. Not easy. The stilted quaintness and archaisms of the dialogue are largely retained from Rafael Sabatini’s 1922 novel, thanks to Casey Robinson’s screenplay. Yes, the words have a certain fascination because they are so quaint, so different from normal usage and seem to fit imagined 17th-century speech: “Faith, yes, I don’t doubt it. You’ve the looks and manners of a hangman.” “It’s entirely innocent I am.” “Bedad, we’ll have a crew yet!” “ . . . while I, who hate this pestilential island—well, such are the quirks of circumstance.” —All lines delivered by Flynn!

There are numerous asides in which Peter Blood usually looks heavenward or to one side of the camera. When he’s a prisoner aboard a slave ship: “It’s a truly royal clemency we’re granted, my friends, one well worthy of King James.” Though fellow slaves are present, he seems oblivious to them. When a Spanish pirate attack saves him from a flogging: “This is what I call a timely interruption, though what’ll become of it, the devil himself only knows.” When he’s toasted, now a pirate: “Well, bedad, methinks the ‘greatest captain on the coast’ has just made the greatest mistake the most ordinary, common fool could make.”

There are numerous asides in which Peter Blood usually looks heavenward or to one side of the camera. When he’s a prisoner aboard a slave ship: “It’s a truly royal clemency we’re granted, my friends, one well worthy of King James.” Though fellow slaves are present, he seems oblivious to them. When a Spanish pirate attack saves him from a flogging: “This is what I call a timely interruption, though what’ll become of it, the devil himself only knows.” When he’s toasted, now a pirate: “Well, bedad, methinks the ‘greatest captain on the coast’ has just made the greatest mistake the most ordinary, common fool could make.”

As for Olivia de Havilland, who had made only one previous film, A Midsummer Night’s Dream earlier that year, Blood offered a much larger role. Her girlish and virginal persona would endure essentially unchanged in the seven subsequent films she made with Flynn, and the two would become one of Hollywood’s great romantic screen couples, á la Tracy and Hepburn, Bogart and Bacall. The charisma between the two, immediately evident in Blood, persists resplendently in all their films.

Unfortunately, Olivia spent most of her screen time waiting for her love to return from somewhere. The plots of three of their films turn tragic. In The Charge of the Light Brigade, their next film after Blood, she prefers his buddy, Patric Knowles, and Flynn ends up dead. She is generally ignored by both Flynn and the camera in Elizabeth and Essex, where he is in a power struggle with Queen Elizabeth (Bette Davis), who sends him to the block. And death also awaits him in their last film together, They Died with Their Boots On—history rewritten, General Custer all hero, none of the fool.

Unfortunately, Olivia spent most of her screen time waiting for her love to return from somewhere. The plots of three of their films turn tragic. In The Charge of the Light Brigade, their next film after Blood, she prefers his buddy, Patric Knowles, and Flynn ends up dead. She is generally ignored by both Flynn and the camera in Elizabeth and Essex, where he is in a power struggle with Queen Elizabeth (Bette Davis), who sends him to the block. And death also awaits him in their last film together, They Died with Their Boots On—history rewritten, General Custer all hero, none of the fool.

The plot of Captain Blood, like the dialogue, is essentially faithful to the novel. It’s 1685, the Duke of Monmouth’s rebellion in England. A doctor, Peter Blood (Flynn), is convicted of treason but saved from the gallows and sold into slavery in Port Royal, Jamaica. He’s lucky again, this time spared the wrath of a brutal overseer by a charming lady, Arabella Bishop (de Havilland). Blood and his fellow slaves capture a Spanish galleon and become pirates. An impressive montage of ship boardings, duels, smoldering cannons and roaring music delineates his growing fame as a pirate, and on the screen, spaced at intervals:

In the pirate haven of Tortuga, Blood signs a compact with French rascal Levasseur (Basil Rathbone).