What you’re saying is if I give up living, I’ll live! – Charley Kyng (Clark Gable)

By the end of the 1940s cracks were beginning to appear in the studio system. With the rise of television and changing popular tastes, the studios began to jettison many of their higher priced stars. To the end though the studios cranked out some pretty good product.

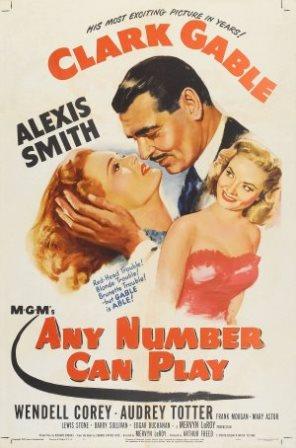

Among these is 1949’s Any Number Can Play, Clark Gable’s final picture of the decade and among the final few he would make for MGM. It’s a rare non-musical production of long-time MGM producer Arthur Freed, who in a long career produced only a handful of such films.

Like most of Gable’s post-war films, Any Number Can Play is a bit more somber and reflective than his earlier pictures while still maintaining some of the old machismo. Here Gable is Charley Kyng, an aging gambler who owns his own gaming house. Immediately we’re confronted by a dark unnamed gentleman calling on Charley. A high stakes gambler or some muscle perhaps?

Actually it’s a doctor Charley’s summoned to get a second opinion on his condition. He confirms that Charley has a heart condition and needs to cut back on all the ‘good things’ in life,’ namely booze and smoking. He also suggests getting out of the gambling business to reduce his chronic levels of stress to which Gable coyly replies, “What you’re saying is if I give up living, I’ll live!”

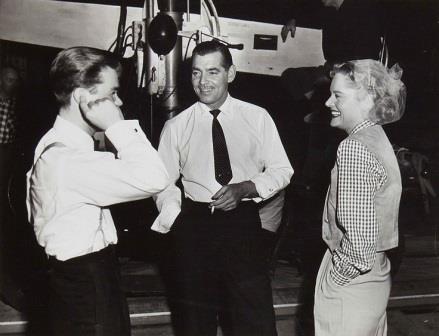

Gable’s character healthwise has quite a few similarities with Gable’s own life, and one can imagine Gable’s on doctor delivering the same message. Gable himself had several heart attacks and smoked up to three packs of cigarettes a day into the last months of his life.

Gable’s character healthwise has quite a few similarities with Gable’s own life, and one can imagine Gable’s on doctor delivering the same message. Gable himself had several heart attacks and smoked up to three packs of cigarettes a day into the last months of his life.

As he gives at least cursory attention cutting back on the drinking and smoking, we’re introduced to his wife (Alexis Smith) and son (Darryl Hickman). It’s clear his long nights at the gambling house and the resulting time away have created a schism with the two of them, with his son being almost openly rebellious.

With his diagnosis confirmed and advice for treatment in hand, Charley’s eyes are opened to the miasma of folks around him. We’re introduced to his craps dealer, who has been skimming on the side with loaded dice to make ends meet. For most of the picture there’s a couple of heavies in the club (notably a young William Conrad) looking to get their owed money.

Adding to the poor man’s stress level is that the dealer (Wendell Corey) is married to his sister in-law (Audrey Totter). They even share the house with them so he Charley can’t escape work even when at home. Though it’s never explained fully what causes the housing arrangement, one can gather that it’s the in-laws inability to pull in enough income.

Adding to the poor man’s stress level is that the dealer (Wendell Corey) is married to his sister in-law (Audrey Totter). They even share the house with them so he Charley can’t escape work even when at home. Though it’s never explained fully what causes the housing arrangement, one can gather that it’s the in-laws inability to pull in enough income.

Among others, we’ve also got a long-term gambler (Lewis Stone) who Gable has bailed out before financially. This time he pawns some of his wife’s jewelry for $500 with Gable’s advice of “I’m sure you know I don’t want to see you in my club tonight.” A few scenes later we see Stone wringing his hands as his money almost literally flies out of his hands at the tables.

There’s also the wife who has managed to gamble away even her wedding ring (which Gable cleverly returns to her), a heavy roller (Frank Morgan) looking to break the house and a fawning mature poker player (Mary Astor) who makes outrageous passes as Gable, wishing she was “only fifteen years younger.”

There’s also the wife who has managed to gamble away even her wedding ring (which Gable cleverly returns to her), a heavy roller (Frank Morgan) looking to break the house and a fawning mature poker player (Mary Astor) who makes outrageous passes as Gable, wishing she was “only fifteen years younger.”

But will Gable be able to walk away from his gambling and the sordid types he calls friends to be with his family? Somewhat as expected, he of course does- though we’ll leave the specifics out.

Any Number Can Play is a good picture, directed effectively by Mervyn LeRoy. Though some have found the film slow moving and melodramatic, the opposite is actually true. A superb supporting cast serve to flesh out Gable’s angst and give the story quite a bit of depth.

Of course the film revolves around Gable as well it should. He’s in his element as he smoothly works from vignette to vignette. Mostly, each of the supporting cast has a scene or two one on one with Gable, and then they mostly effortlessly fold back into the woodwork. Two are notable among these; Mary Astor, Gable’s co-star in 1932’s Red Dust, makes a heartbreakingly depressing play for Gable. Also is Lewis Stone as Ben Snelerr, the habitual gambler who has resorted to pawning jewelry to fuel his habit. In retrospect it would have been good to have a bit more interplay between some of these intriguing characters.

Of course the film revolves around Gable as well it should. He’s in his element as he smoothly works from vignette to vignette. Mostly, each of the supporting cast has a scene or two one on one with Gable, and then they mostly effortlessly fold back into the woodwork. Two are notable among these; Mary Astor, Gable’s co-star in 1932’s Red Dust, makes a heartbreakingly depressing play for Gable. Also is Lewis Stone as Ben Snelerr, the habitual gambler who has resorted to pawning jewelry to fuel his habit. In retrospect it would have been good to have a bit more interplay between some of these intriguing characters.

Frank Morgan as big roller Jim Jurstyn is the only of the supporting players who has extended interplay with Gable, having a few quips back and forth early in the picture to setup their late feature duel at the craps table.

As strong as the interplay is at the tables the dynamic between Gable and his casted family fares much worse. Alexis Smith as his wife, feels transparent and unhappy in her role- which she well could have been as she was on loan to MGM for Any Number Can Play from her usual home at Warners, which she much preferred. In addition she isn’t photographed well here, looking tired and shadowy which surely wasn’t the intention.

As strong as the interplay is at the tables the dynamic between Gable and his casted family fares much worse. Alexis Smith as his wife, feels transparent and unhappy in her role- which she well could have been as she was on loan to MGM for Any Number Can Play from her usual home at Warners, which she much preferred. In addition she isn’t photographed well here, looking tired and shadowy which surely wasn’t the intention.

Darryl Hickman as Gable’s on-screen son fares still worse. Though perhaps partly a show of the character’s dislike of gambling and the like it feels like he is almost dragged into the scenes and forcibly held there by Gable and more noticeably by Mary Astor. In a scene that is tortuous to watch, Astor, having learned that the young scamp who suddenly appeared in the club is Charley’s child. Whether to size the youngster up either as worthy of her own attention (as a potential stand-in for spurned advances from his father) or as worthy of Charley’s name, it is absolutely painful to watch.

A forgotten and frequently overlooked tidbit in Gable’s late MGM career, Any Number Can Play shows a great story of the powers of gambling addiction coupled with a superb supporting cast and- of course, the King himself, Clark Gable. It’s embarrassing to see the lack of engagement on it’s imdb page.