Follow Inspector Cockrill in the footsteps of . . . MURDER.

A World War II setting, hospital intrigue, mystery and murder, and a good dose of British humor from an actor who practically steals the movie. If a viewer pays too much attention and, say, takes things for what they seem, he might think he’s discerned the murderer rather early in 1947’s Green for Danger. He’d be wrong, for red herrings abound, for even at the last moment, when the solution seems solved—oops, a misdirection.

Between 1939 and 1945, Hollywood saturated the world with war films, even paying sentimental tribute in 1942 to the British spirit during the blitz with Mrs. Miniver. Technically and aesthetically a better film than any English studio could make at the time, it is more than a bit unrealistic and sugary sentimental, the idealization of an England that, really, never existed.

Green for Danger, made two years after the war, shows the more realistic British viewpoint, what the citizens of those islands, especially of London, had to endure—the air raids, the horror of the V-I flying bombs and the trauma of wondering if their houses would be there when they returned home. There was ever the threat, certainly the annoyance, of Nazi propaganda on the wireless and the infamous Lord Haw-Haw. It’s a similar voice, only feminine, that plays into the mystery of the movie.

The film begins, however, with another voice, a narration:

“ ‘To the assistant commissioner of police, Scotland Yard: Sir: The amazing events which I am reporting are said to have begun on August 17, 1944.’ New paragraph. ‘The postman was cycling up Heron’s Hill, on his way to deliver mail at the hospital. His name was Joseph Higgins. I begin with him because . . . he was the first to die.’ ” So the movie begins, a Scotland Yard detective dictating a letter for his superior.

“ ‘To the assistant commissioner of police, Scotland Yard: Sir: The amazing events which I am reporting are said to have begun on August 17, 1944.’ New paragraph. ‘The postman was cycling up Heron’s Hill, on his way to deliver mail at the hospital. His name was Joseph Higgins. I begin with him because . . . he was the first to die.’ ” So the movie begins, a Scotland Yard detective dictating a letter for his superior.

Already it’s obvious this little story is going to unfold as a flashback, the detective is to narrate and Higgins is going to die—and with the suggestive “first,” it can be assumed there’ll be more deaths.

This technique of anticipating the action—the famous cliché, “had he only known that . . . ”—violates an old rule of mystery writing: for the benefit of the reader and to sustain the suspense and integrity of a whodunit, never move ahead of the story.

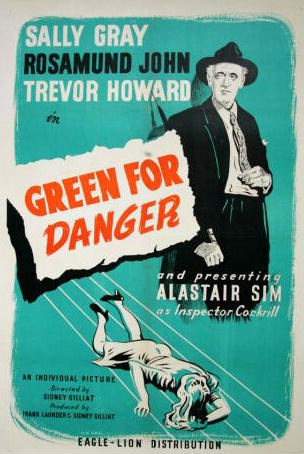

But it works here, partly because of the droll narration, the cocky confidence of the detective and mainly because of Alastair Sim as Inspector Cockrill. With his bald head, doleful appearance, incisive diction and eccentric, yet graceful gestures, he’s the most charismatic, laid-back detective since the fascinating Nick Charles (William Powell). Sim has the same light, even sarcastic view of crime and the criminal while still retaining his authority and, veiled in false whimsy, an eagle-eye perception.

But it works here, partly because of the droll narration, the cocky confidence of the detective and mainly because of Alastair Sim as Inspector Cockrill. With his bald head, doleful appearance, incisive diction and eccentric, yet graceful gestures, he’s the most charismatic, laid-back detective since the fascinating Nick Charles (William Powell). Sim has the same light, even sarcastic view of crime and the criminal while still retaining his authority and, veiled in false whimsy, an eagle-eye perception.

Coincidentally, the last of the six Charles/Powell films, The Song of the Thin Man, appeared in 1947, the year of Green for Danger. Powell has here a worthy successor, even though Sim’s Cockrill is a rarity, a detective who sleuths without a partner. Nor does he have, like Charles, a wife, though Nora provides banter and romantic interest—and, whatever Sim’s persuasive qualities, it’s hard to imagine him as “romantic.”

Sim, who appears in Alfred Hitchcock’s Stage Fright (1950), has been a detective or policeman before and after Green for Danger—in The Riverside Murder (1935), Gangway (1937), in three films as Sergeant Bingham and in An Inspector Calls (1954). Sleuthing aside, he even made two films, The Bells of St. Trinian’s (1954) and Blue Murder at St. Trinian’s (1957), in which he appears in drag.

Alastair Sim, however, is best remembered for being the definitive Ebenezer Scrooge in the definitive version of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1951). With his humbug view of Christmas, and the empty-eyed look of a misanthrope who is unhappy, dispassionate and sinister, and, yes, even unkind, Sim transforms Scrooge, by story’s end, into a carrying, now compassionate soul. The metamorphosis is an acting miracle, and, very possibly, exactly what Dickens would recognize as the personification of his character.

Alastair Sim, however, is best remembered for being the definitive Ebenezer Scrooge in the definitive version of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1951). With his humbug view of Christmas, and the empty-eyed look of a misanthrope who is unhappy, dispassionate and sinister, and, yes, even unkind, Sim transforms Scrooge, by story’s end, into a carrying, now compassionate soul. The metamorphosis is an acting miracle, and, very possibly, exactly what Dickens would recognize as the personification of his character.

At Heron’s Park Hospital, long before Higgins’ death and Inspector Cockrill’s arrival, romantic competition pulsates between doctors Barnes (Trevor Howard) and Eden (Leo Genn) over the affections of nurse “Freddi” Linley (Sally Gray). There are, as well, suspicious antagonisms and nervous tension among the entire staff, including the five nurses who assist the two doctors.

During one operation, the staff hears a buzz-bomb roar overhead. “Hope it missed my house,” Eden says.

It’s the same doodlebug postman Joe Higgins (Moore Marriott) hears as he is pedaling his way to the hospital. As he takes cover in a roadside shelter, he hears a woman’s voice spewing Nazi propaganda from a wireless. He and an air raid warden listen tensely to the V-I’s sound, the engine cut out and the momentary silence before it plunges to earth. The shelter receives a direct hit and among the debris are an injured Higgins and the persistent, undamaged wireless: “This is Germany calling. This is Germany calling.”

It’s the same doodlebug postman Joe Higgins (Moore Marriott) hears as he is pedaling his way to the hospital. As he takes cover in a roadside shelter, he hears a woman’s voice spewing Nazi propaganda from a wireless. He and an air raid warden listen tensely to the V-I’s sound, the engine cut out and the momentary silence before it plunges to earth. The shelter receives a direct hit and among the debris are an injured Higgins and the persistent, undamaged wireless: “This is Germany calling. This is Germany calling.”

Higgins, with a non-life-threatening injury, is wheeled on a gurney down a hall to the operating theatre. The shadows falling across his face, views of the ceiling passing overhead and the ominous music—all due to the moody camera of Wilkie Cooper and atmospheric score of William Alwyn. Higgins asks Dr. Barnes, “You gonna do the anesthetic? . . . You got a nerve.” Moments later, hearing the voice of nurse Woods (Megs Jenkins), he says, “I know that voice! I’ve head it before.” Soon after the operation, Higgins dies. Seems Dr. Barnes had lost an earlier patient under similar circumstances.

Two suspicious inferences already, two possible suspects, but there have been and will be many more hints—shifty glances, cutting innuendos and figures in the shadows. Another nurse (Judy Campbell) announces from a balcony during a hospital staff dance that Higgins’ death was no accident and she knows who killed him. In her attempt to retrieve the evidence from a medicine cabinet, she is killed by someone in a hospital gown and operating mask.

Two suspicious inferences already, two possible suspects, but there have been and will be many more hints—shifty glances, cutting innuendos and figures in the shadows. Another nurse (Judy Campbell) announces from a balcony during a hospital staff dance that Higgins’ death was no accident and she knows who killed him. In her attempt to retrieve the evidence from a medicine cabinet, she is killed by someone in a hospital gown and operating mask.

It’s only now, thirty-eight minutes into the film, that Scotland Yard is called in . . . and none other than——

“It was early the next morning, the nineteenth, that I myself, in person, arrived on the scene.” Inspector Cockrill’s introduction, as he is walking to the hospital, is soon interrupted by the sound of another doodlebug, and in an effort to find cover, he trips negotiating a fence. The bomb lands elsewhere. He slowly picks himself up, casually loops his umbrella shaft through the handle of his briefcase, puts the shaft over his shoulder and nimbly jumps the fence, all to Alwyn’s comical violins and woodwinds.

Later, after drawing the five suspects together—“We’ll pause thirty seconds,” he says, “while you cook up your alibis.”—he announces that a bottle in the medicine cabinet is missing four pills—lethal pills, of course. Cockrill requests a tour of the operating theatre, telling Dr. Barnes, “You must bear with me, doctor. I’m a child in these matters.” Barnes explains the three cylinders—black and white for oxygen, black for nitrous oxide and green for carbon dioxide.

Later, after drawing the five suspects together—“We’ll pause thirty seconds,” he says, “while you cook up your alibis.”—he announces that a bottle in the medicine cabinet is missing four pills—lethal pills, of course. Cockrill requests a tour of the operating theatre, telling Dr. Barnes, “You must bear with me, doctor. I’m a child in these matters.” Barnes explains the three cylinders—black and white for oxygen, black for nitrous oxide and green for carbon dioxide.

After Barnes has left, Cockrill sits alone, spinning on a stool, in his lap the umbrella and briefcase. “There was the vital evidence,” his voice-over continues, “the clue to the whole business, right under my nose. If I’d known then, it might have saved another life.”

And strolling through a hospital hall: “My presence lay over the hospital like a pall. As I approached, the voices were hushed, all eyes turned upon me. Who was the guilty one, when will he be arrested, who will be next? That is what they were all thinking. I found it all tremendously enjoyable.”

The tensions mount, suspicions fester, arguments continue—all partially relieved by Cockrill’s sardonic, unhurried humor. At one point when Barnes and Eden engage in a fist fight and end up on the floor, the inspector draws up a chair to watch, leaning over them like a patient vulture waiting for a meal.

Nurse Sanson (Rosamund John) rescues Linley from possible asphyxiation from a gas heater, but even this—can this be taken at face value? During her rescue, Linley falls down the stairs, suffering a head injury that renders her unconscious. Later, known only to the hospital director (Ronald Adam) and the inspector, she recovers completely.

Nurse Sanson (Rosamund John) rescues Linley from possible asphyxiation from a gas heater, but even this—can this be taken at face value? During her rescue, Linley falls down the stairs, suffering a head injury that renders her unconscious. Later, known only to the hospital director (Ronald Adam) and the inspector, she recovers completely.

A trap set for a criminal is a frequent subterfuge and for a detective as wily as the inspector, the idea comes naturally. What else but to re-enact Higgins’ operation, with the same participants and wheel in Linley, faking a coma! (Not too much logic here: Higgins’ and Linley’s injuries are totally different—and she is in no way prepped for cranial surgery.)

When Linley fails to respond to the oxygen, Cockrill, after glancing at those around the operating table and seeing the final clue, a black smudge on a gown, orders a shutdown of the operation. And, lo and behold, he scrapes black paint from the white and black oxygen cylinder to reveal . . . a green base. A carbon dioxide tank! A spare oxygen cylinder is readied, and Linley revives. (Not being unconscious to start with, how could she be deprived of oxygen and not react, gasp for air?!)

During the typical insinuations as Cockrill moves from one individual to another, one person races from the room, followed by another with a hypodermic needle.

Well, turns out . . . guess this much can be revealed . . . the double murderer, who had broken into the medicine cabinet, has swallowed the four pills before the operation. Another person had the antidote in the hypodermic, which Cockrill knocks away, causing the murderer’s death. This is too excellent a whodunit to identify the murderer and spoil it for those who have not seen the film.

Well, turns out . . . guess this much can be revealed . . . the double murderer, who had broken into the medicine cabinet, has swallowed the four pills before the operation. Another person had the antidote in the hypodermic, which Cockrill knocks away, causing the murderer’s death. This is too excellent a whodunit to identify the murderer and spoil it for those who have not seen the film.

Even the cocky Cockrill is stunned—and guilty, in his own way, of a death. Could it be that once, just this once, in this case, he, in person, has erred?— Cockrill’s dictation of his continuing letter to his Scotland Yard boss reflects as much, that “ . . . it still seems to me that I fell down rather badly on the case.”

Cockrill is leaving the hospital, once again on foot, when he hears another roar. He looks again for cover from the expected V-I, only to be embarrassed that it’s a motorcycle.

“ ‘In view of my failure—correction, comparative failure—I feel that I have no alternative but to offer you, sir, my resignation, in the sincere hope that you will not accept it.’ Full stop.”