“If the worst comes to the worst, I can always get a job haunting a house.” — Geoffrey Radcliffe

After the success, critical and financial, of The Invisible Man in 1933, it’s curious why Universal Pictures, the studio which could never make too many horror movies, waited seven years before creating a sequel. In the remaining years of the 1930s cameBride of Frankenstein in 1935, Dracula in 1936, Son of Frankenstein at the beginning of 1939 and, in November of that year, Universal’s last horror-like investment of the decade, Tower of London, with Vincent Price.

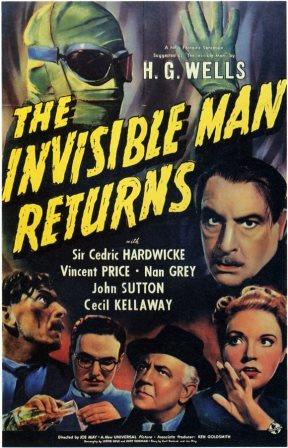

Released two weeks into 1940, Price’s next movie, second-billed to Cedric Hardwicke, was The Invisible Man Returns. The actor had fallen into the horror genre, if not intentionally on anyone’s part, then clearly it was the first of some creepily suggestive roles that, during the next two decades, would lead to his golden years of horror in the 1960s.

Although Tower of London is not technically a horror film as such, more of an historical drama, Price, as a duke to Basil Rathbone’s Richard III, is drowned in a wine vat, a fate worthy of a horror film. In 1940, in the Hawthorne classic House of Seven Gables, again with Gothic overtones, Price is falsely imprisoned though exonerated, one of his few heroic roles. In Laura (1944), in one of his best straight parts, he is cleared of “murdering” the title lady (Gene Tierney) who was alive all along. Then two years later he is cast as Nicholas Van Ryn in the heavily Gothic Dragonwyck, again, not strictly a horror exercise. Van Ryn, however, is sinister and morose, a cunning wife-killer and dope addict.

Price’s roles varied and were generally, sadly, “respectable” (non-horror) for seven years—as the villainous Richelieu in The Three Musketeers (1948), a soap company tycoon in the comedy Champagne for Caesar (1950) opposite the dignified Ronald Colman and a sea captain in the stodgy Errol Flynn costumer Adventures of Captain Fabian (1951).

Price’s roles varied and were generally, sadly, “respectable” (non-horror) for seven years—as the villainous Richelieu in The Three Musketeers (1948), a soap company tycoon in the comedy Champagne for Caesar (1950) opposite the dignified Ronald Colman and a sea captain in the stodgy Errol Flynn costumer Adventures of Captain Fabian (1951).

Price also made forays into the new medium of television during this time, appearing in Fireside Theatre, Chesterfield Presentsand Robert Montgomery Presents.

Then came the milestone year 1953 and his plunge into the demonic world of a bona fide horror film, House of Wax. Now as a mad exhibitor of a wax museum, he is, first, facially scarred by a fire, then burnt to a crisp in his own incinerating machine.

But once again Price treaded water through some average films, Hollywood apparently numb to both the potential of House of Wax and to his intuitive instincts for the macabre. Until 1960, that is. Then, in the Edgar Allan Poe-based House of Usher, perhaps the best, certainly the most intelligent, of his horror films, the actor hit his stride, plunging officially and irrevocably—wonderfully as he saw it—into the genre that would make him famous. During the ’60s, after a salute to Jules Verne in Master of the World, came more Poe adaptations: The Pit and the Pendulum, Tales of Terror, The Raven, The Masque of the Red Death,The Tomb of Ligeia and many others.

In 1962, a new, more grotesque and elaborate Tower of London, now an official horror film. At the Battle of Bosworth, Price, promoted from a duke in 1939 to King Richard III, swings his sword at the ghosts of those he had killed to obtain the throne. He is thrown from his horse and impaled on an upturned battleaxe—perhaps a fresh perspective on the mystery of how the real Richard died. As good as any, perhaps.

In 1962, a new, more grotesque and elaborate Tower of London, now an official horror film. At the Battle of Bosworth, Price, promoted from a duke in 1939 to King Richard III, swings his sword at the ghosts of those he had killed to obtain the throne. He is thrown from his horse and impaled on an upturned battleaxe—perhaps a fresh perspective on the mystery of how the real Richard died. As good as any, perhaps.

Marking the end of the decade in 1969, The Oblong Box is based, as seems only right, on a Poe short story of 1844. The film, however, is a considerable decline after House of Usher. The direction is sluggish and, worse, there are no production pluses to offset Price’s hammy tendency, which, sometimes an endearment, can often be accepted in other films.

Returning, now, thirty years, 1940 is a gentler, less gory time for the movies. The Invisible Man Returns as a sequel to The Invisible Man is in no way the equal of the original, but it remains one of Universal’s better films in the genre. The positives are a credible performance by Cedric Hardwicke, the presence of Vincent Price—his voice, anyway—and a delectable array of some favorite old supporting players—Forrester Harvey, Mary Gordon, Billy Bevan, George Lloyd, Harry Cording, Colin Kenny and Ivan F. Simpson.

Returning, now, thirty years, 1940 is a gentler, less gory time for the movies. The Invisible Man Returns as a sequel to The Invisible Man is in no way the equal of the original, but it remains one of Universal’s better films in the genre. The positives are a credible performance by Cedric Hardwicke, the presence of Vincent Price—his voice, anyway—and a delectable array of some favorite old supporting players—Forrester Harvey, Mary Gordon, Billy Bevan, George Lloyd, Harry Cording, Colin Kenny and Ivan F. Simpson.

The central novelty of The Invisible Man Returns are John F. Fulton’s special effects, which are rarely more sophisticated or advanced than his work in the original film. Here again are the same photographic tricks—the unraveling of bandages that reveals an unseen man, the seemingly magical removal of clothes from a suitcase, the struggle of a supposed guinea pig in a restraining collar and its materialization, the detachment of spark plug wires from a car engine and a villain fighting an unseen adversary.

His face swathed in bandages, with only his voice for expression, Price’s one visible materialization at the end of the film represents, by far, the most advanced special effect, superior to a similar scene for Claude Rains in The Invisible Man. First, there’s the skeletal frame, then the slowly added blood vessels, then muscles, then skin, and, finally, the face of Vincent Price.

His face swathed in bandages, with only his voice for expression, Price’s one visible materialization at the end of the film represents, by far, the most advanced special effect, superior to a similar scene for Claude Rains in The Invisible Man. First, there’s the skeletal frame, then the slowly added blood vessels, then muscles, then skin, and, finally, the face of Vincent Price.

Geoffrey Radcliffe (Price) is awaiting execution for the murder of his brother Michael, which he did not commit. Dr. Frank Griffin (John Sutton) makes a brief visit to his cell, injecting him with an invisibility drug developed by his brother Jack (Rains in the original). Moments before he is to be executed, Geoffrey disappears, leaving only his clothes in a corner of the prisoner.

Scotland detective Sampson (Cecil Kellaway) suspects the truth and tries to persuade Frank to tell where Geoffrey has gone. But the chemist, who plays ignorant, saying he was never interested in his friend’s affairs, is actually experimenting with guinea pigs for an antidote to the invisibility drug, to make Geoffrey visible again. (In the original movie, the drug is “monocaine,” now it’s called “duocaine.”) The animals do become visible but soon die.

In the meantime, Geoffrey has arrived at the home of his sweetheart, Helen (Nan Grey), his face wrapped in bandages and wearing the familiar dark glasses. He’s out to find the real murderer, but tells her, “Frank gave me his word that if my mind should begin to go before he found a way back for me, he’d prevent my doing any harm, chains if necessary.”

Willie Spears (Alan Napier), an employee of a mining company owned by Richard Cobb (Hardwicke), Geoffrey’s cousin, leaves the mine office. Unknown to him, Geoffrey, sans clothes, has caught a ride on his car. When the car stalls and Willie alights to check, he finds a loose spark plug wire, and thus the humor of trying to reattach it as the invisible Geoffrey continues to unplug it.

Willie Spears (Alan Napier), an employee of a mining company owned by Richard Cobb (Hardwicke), Geoffrey’s cousin, leaves the mine office. Unknown to him, Geoffrey, sans clothes, has caught a ride on his car. When the car stalls and Willie alights to check, he finds a loose spark plug wire, and thus the humor of trying to reattach it as the invisible Geoffrey continues to unplug it.

Frightened, Willie flees into the woods. There, under the unnerving special effects—a stick suspended in midair, struck by invisible blows and Geoffrey’s disembodied voice—he reveals that Cobb is the murderer.

In a final confrontation with Scotland Yard, Cobb falls from a coal cart and is killed. Geoffrey, struck by a bullet from Sampson’s gun, is able to reach Frank. With a blood transfusion, Geoffrey becomes visible—why didn’t Frank think of a blood transfusion before?!—and the doctors, now able to see him, can operate and remove the bullet.